|

|

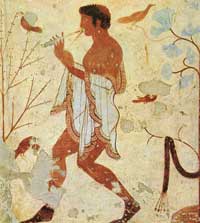

Feast of Lars Velch, the Tomb of The Shields, Necropolis of Tarquinia |

|

|

Tarquinia, a medieval town famous for its archeological remains, is situated just a few kilometres from Tuscany, in Northern Lazio, very close to Capalbio and Monte Argentario and less than an hour drive from Podere Santa Pia. |

| The Necropolises of Cerveteri and Tarquinia constitute a unique and exceptional testimoney of the ancient Etruscan Civilization, the only urban civilization of the pre-Roman Age. The frescoes inside the tombs – true-to-life reproductions of Etruscan homes – are faithful depictions of this disappeared culture’s daily life. These tumuli or burial mounds reproduce the homes in their various types of constructions; because they were built to mirror the Etruscan habitation itself, they are the only examples left of such in any form anywhere. The two necropolises of northern Lazio are identical replications of the Etruscans' urban grid, and are among the primary exemplars of burial centers or hubs that one can find in Italy. The necropolis of Banditaccia in Cerveteri was developed from the 9th Century B.C., and then expanded beginning with the 7th Century, following a well-defined urban plan. Similar is the developmental history of the necropolis of Monterozzi in Tarquinia. Both the painted tombs of the nobles and those in more simple styles are singular and extraordinary testaments to Etruscan quotidian life, as well as their ceremonies, mythology and even their artistic capacities. Cerveteri’s Necropolis |

|

The Tomba della Rilievi, Necropoli della Banditaccia, near Cerveteri |

The necropolis tombs have very different traits one from the other, depending on the construction period and technique. Those located in the vast archaeological site of Cerveteri are in the thousands. |

|

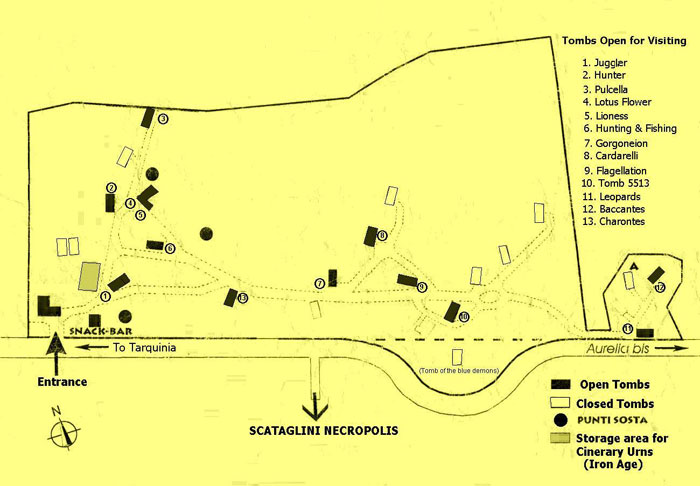

Enlarge map Tarquinia Monterozzi necropolis, area of Calvario [1] |

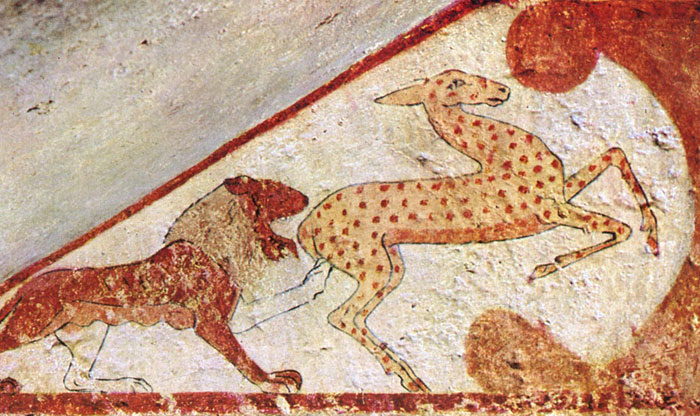

| The Tomb of the Leopards |

| The Tomb of the Leopards (or Tomba dei Leopardi) is an Etruscan burial chamber so called for the confronted leopards painted above a banquet scene. The tomb is located within the Monterozzi necropolis and dates to around 480–450 BC.[2] The painting is one of the best-preserved murals of Tarquinia,[3] and is known for "its lively coloring, and its animated depictions rich with gestures."[4] |

|

Tomb of the Leopards, confronted leopards above a banqueting scene |

The banqueters are "elegantly dressed" male-female couples attended by two nude boys carrying serving implements. The women are depicted as fair-skinned and the men as dark, in keeping with the gender conventions established in the Near East, Egypt and Archaic Greece. The arrangement of the three couples prefigures the triclinium of Roman dining.[5]

Artistically, the painting is regarded as less sophisticated and graceful than that found in the Tomb of the Bigas or the Tomb of the Triclinium[18] The tomb of the Triclinium |

|

||||

Tomba delle Leonesse (The Tomb of the Lioness) |

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Tarquinia, Tomb of the Lionesses (cardarelli, danzatrice) |

||||

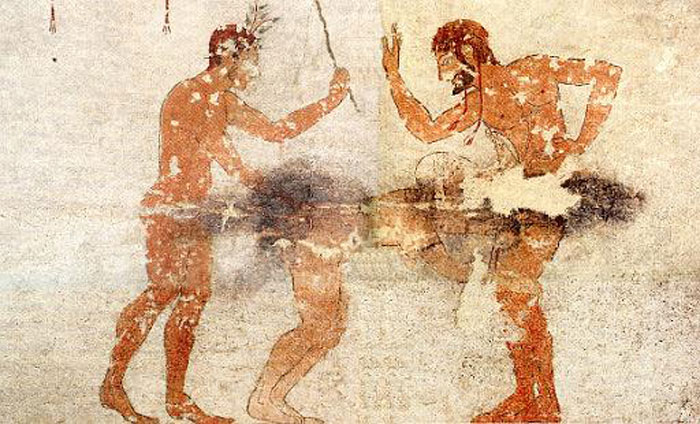

Tomba della Fustigazione

|

||||

|

||||

Tomba della Fustigazione, fresco painting inside the tomb where two men are portrayed flagellating a woman with a cane and a hand during an erotic situation |

||||

| The Hunting and Fishing Tomb |

||||

The Hunting and Fishing Tomb is composed of two chambers. In the first, there is a depiction of Dionysian dancing in a sacred wood, and in the second, a hunting and fishing scene and portraits of the tomb owners. The painted tombs of the aristocracy, as well as more simple ones, are extraordinary evidence of what objects cannot show: daily life, ceremonies and mythology as well as artistic abilities.[0]

|

||||

|

||||

Tarquinia, Tomb of the Hunting and Fishing (Tomba della Caccia e Pesca) |

||||

| The Tomb of Orcus |

||||

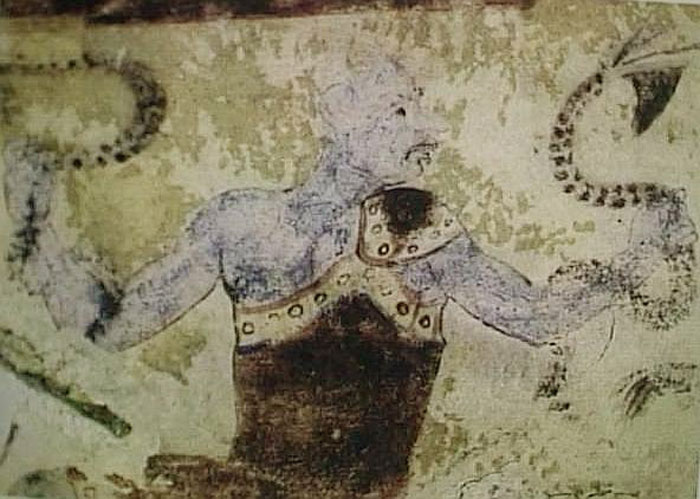

| The Tomb of Orcus (Italian: Tomba dell'Orco), sometimes called the Tomb of Murina (Italian: Tomba dei Murina), is a 4th century BC Etruscan hypogeum (burial chamber). Discovered in 1868, it displays Hellenistic influences in its remarkable murals, which include the portrait of Velia Velcha, an Etruscan noblewoman, and the only known pictorial representation of the demon Tuchulcha.[19] In general, the murals are noted for their depiction of death, evil, and unhappiness.[20] Because the tomb was built in two sections at two stages, it is sometimes referred to as the Tombs of Orcus I and II; it is believed to have belonged to the Murina family, an offshoot of the Etruscan Spurinnae. The Tomb of Orcus I (also known as the Tomb of Velcha) was constructed between 470 and 450 BC. The main and right walls depict a banquet, believed to be the Spurinnae after their death in the Battle of Syracuse.[20][21] The banqueters are surrounded by demons who serve as cupbearers. One of the banqueters is a noblewoman named Velia Velcha (or by some interpretations, Velia Spurinna), whose portrait has been called the "Mona Lisa of antiquity".[22][23]

|

||||

|

||||

Detail, Velia Velcha, as pictured on the right wall of Orcus I, Tomb of Orcus, Tarquinia, 4th century B.C. |

||||

| 'These (Theseus) threatened by a demon, Tomb of Orcus, Tarquinia. Theseus is known for killing the Minotaur of King Minos to save the lives of the Athenian children sent in sacrifice to it; but he had many adventures, and the one shown here involved his friend Peirithoüs, with whom he had abducted the daughter of Zeus, Helen, when she was about 11 years old. Later she was abducted by Paris a prince of Troy. But Peirithoüs later convinced Theseus that they ought to abduct Hades' wife, Persephone. Hades froze them there in a "state of forgetfulness," frozen by snakes, until Hercules found them there and rescued Theseus and some say Peirithoüs was freed as well.'[24] | ||||

| The Tomb of the Augurs |

||||

|

||||

| Tomb of the Augurs, back wall, scene of two Augurs, with inscription, "The priest, he stands, to pass." |

||||

'The Tomb of the Augurs is very impressive. On the end wall is painted a doorway to a tomb and on either side of it is a man making what is probably the mourning gesture, strange and momentous, one hand to the brow. The two men are mourning at the door of the tomb.

|

||||

|

||||

Tomb of the Augurs, nude wrestlers on the side walls |

||||

| 'This picture is supposed to reveal the barbarously cruel sports of the Etruscans. But since the tomb contains an augur, with his curved sceptre, tensely lifting his hand to the dark bird that flies by: and the wrestlers are wrestling over a curious pile of three great bowls; and on the other side of the tomb the man in the conical pointed hat, he who holds the string in the first picture, is now dancing with a peculiar delight, as if rejoicing in victory or liberation: we must surely consider this picture as symbolic, along with all the rest: the fight of the blindfolded man with some raging, attacking element. If it were sport there would be onlookers, as there are at the sports in the Tomb of the Chariots; and here there are none. However, the scenes portrayed in the tomb are all so real, that it seems they must have taken place in actual life. Perhaps there was someform of test or trial which gave a man a great club; tied his head in a sack, and left him to fight a fierce dog which attacked him, but which was held on a string, and which even had a wooden grip-handle attached to its collar, by which the man might seize it and hold it firm, while he knocked it on the head. The man in the sack has very good chances against the dog. And even granted the thing was done for sport, and not as some sort of trial or test, the cruelty is not excessive, for the man has a very good chance of knocking the dog on the head quite early. Compared with Roman gladiatorial shows, this is almost 'fair play''.'[25] |

||||

| The Tomb of the Blue Demons |

||||

|

||||

Tomb of the blue Demons, Tarquinia |

||||

The Tomb of the Blue Demons was only discovered in 1985, after being found during some road works. It is located by the side of the road, adjacent to the Calvario area of the Monterozzi necropolis, although it is not usually open to the public. It is named after the blue and black skinned demons depicted on the right hand wall. (ca. 440-430 B.C.)

|

||||

|

||||

Tomb of the blue Demons (detail), Tarquinia |

||||

| The Tomb of The Shields |

||||

|

||||

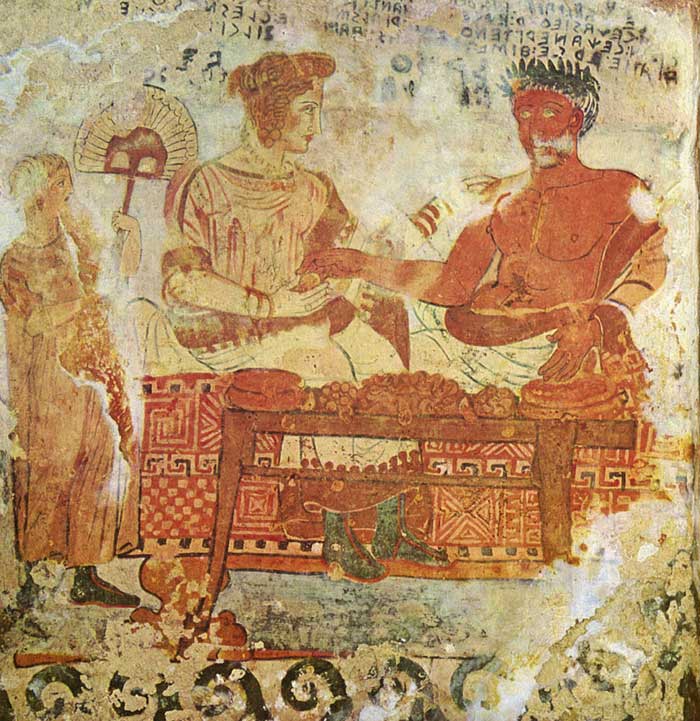

Feast of Velthur Velch, the Tomb of The Shields |

||||

| The Tomb of the Shields, ( dated 340 BCE and discovered in 1870), is a large and complex hypogeum with four doorways, one in the central position and linked to a room at the back, with two others on the sides, linked through doors and windows, all decorated with painted frames. Its name derived by the fact that walls of the room at the rear of the tomb are decorated with numerous golden shields. A number of scenes are painted on the entrance wall, showing members of the Velcha family, the tomb occupants. On right of the wall in front of yo , there is a banquet, with Larth Velcha reclining on his bed with his wife Velia Seitithi, who is passing him an egg, symbol of rebirth, often reproduced in Etruscan tomb paintings. She is well dressed, and is seated next to her husband's feet, as was the custom. Not far from them, on the right wall, two other members of the family, Velthur and Arnth, the grandparents of Larth, are standing, dressed in large cloaks. They are accompanied by two young musicians. On the left wall Velthur and Ravnthiu appear again, but this time, they sit on folded stools. Velthur is holding a sceptre, symbol of his power. Over the windows, winged Spirits appear.[26] Mother of Lars Velch. Detail. Tarquinia, |

|

|||

[0] UNESCO World Heritage Sites | The Necropolises of Tarquinia and Cerveteri

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Tomba del Fiore di Loto, Tomb of the Lotus Flower, one of the Etruscan grave chambers of Monterozzi Necropolis |

||||

'Plants, flowers and perfumes are not strongly featured in Etruscan studies even though they are present in many paintings and reliefs.

[Source: Jean-René Jannot, The Lotus, Poppy and other Plants in Etruscan Funerary Contexts | www.britishmuseum.org (pdf)]

|

||||

|

||||

Tarquinia, Tomba dei Baccanti |

||||

Monuments and Archaeological Sites Opening Times The National Etruscan Museum |

||||

| Tarquinia, as we know it today, was called Corneto up until the 19th century. The name Corneto may derive from the presence of plants of Corniolo (Corgnitum), or perhaps from the mythical king, Corito, its founder and ancestor of Aeneas. The city has indefinable origins. It was a Catholic Episcopalian center beginning in the 4th century A.D. Petrarch defined Corneto as "Turritum et spectabile oppidum, gemino cinctum muro". In other words, a beautiful, fortified town surrounded by a double wall that dominated the view of travelers with its 38 majestic towers. Since the middle of the 12th century it was a free city, in the 13th century the city reinforced its status and increasingly tied to Rome, which was the best buyer of the rich production of wheat. Between the end of the 15th century and the beginning of the 16th Corneto suffered the onslaught of two grave pestilences which reduced the population to two thirds of what it had been and contributed to the decadence of the city's architectural patrimony. At the end of the 18th century and again at the beginning of the 19th century, the city was twice occupied by French troops. In 1815 Corneto returned under the reign of the Church as a Papal State and in 1870 was annexed by the kingdom of Italy. Finally in 1872 the city assumed the name of Corneto-Tarquinia and then definitely that of Tarquinia in 1922. Throughout the course of time Tarquinia continued to be enriched with splendid palaces and churches all of which were subject to the predominant culture at the moment of construction as well as to the tastes of who governed within the Papal State or who wielded power. Today wandering through the winding streets of Tarquinia one can note Roman style architecture from the 12th-14th century along with Gothic and Renaissance motifs intertwine. The educated eye can spot Renaissance, Baroque and Neoclassical palaces with a variety of forms and decorations. This eclectic trend continued in the phase after Italy was united and has spread throughout the major part of Italy. [Source: Informazioni Tarquinia | www.tarquiniaturismo.itl] |

|

|||

|

This article incorporates material from the Wikipedia articles Tomb of the Leopards, Tomba della Fustigazione, Tomb of Orcus published under the GNU Free Documentation License.

|

||||

|

Enlarge map |

||||

Comuni of the Province Viterbo | Acquapendente · Arlena di Castro · Bagnoregio · Barbarano Romano · Bassano Romano · Bassano in Teverina · Blera · Bolsena · Bomarzo · Calcata · Canepina · Canino · Capodimonte · Capranica · Caprarola · Carbognano · Castel Sant'Elia · Castiglione in Teverina · Celleno · Cellere · Civita Castellana · Civitella d'Agliano · Corchiano · Fabrica di Roma · Faleria · Farnese · Gallese · Gradoli · Graffignano · Grotte di Castro · Ischia di Castro · Latera · Lubriano · Marta · Montalto di Castro · Monte Romano · Montefiascone · Monterosi · Nepi · Onano · Oriolo Romano · Orte · Piansano · Proceno · Ronciglione · San Lorenzo Nuovo · Soriano nel Cimino · Sutri · Tarquinia · Tessennano · Tuscania · Valentano · Vallerano · Vasanello · Vejano · Vetralla · Vignanello · Villa San Giovanni in Tuscia · Viterbo · Vitorchiano

|

||||

| Wine regions | Podere Santa Pia |

Pienza |

||

Villa La Foce In the background Monte Amiata |

Siena, duomo |

Siena, Piazza del Campo |

||

|

||||

Podere Santa Pia, April |

||||