|

|

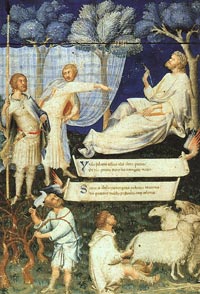

Simone Martini, Frontispiece to Petrarch's Virgil (detail) (c. 1336), illuminated manuscript, 29,5 x 20 cm, Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Milan |

|

Simone Martini | Frontispiece to Petrarch's Virgil |

| Simone Martini was born in 1284. Though little is known of his artistic origins (Vasari gives Giotto as his teacher) he appears as a fully developed master when he painted the Majestas in the Sala del Consiglio of the Siena Town Hall in 1315. Simone Martini spent his last years at the papal court in Avignon, where he arrived in 1340 accompanied by his brother and collaborator, Donato.[1] They came to Avignon as artists and as official representatives of the Church in Siena. Only one signed and dated work is known from this period in France, the Holy Family (1342; Liverpool). Frescoes in the Cathedral are in a ruined state. A group of four small panels with scenes of the Passion and an Annunciation diptych (now in various museums) project a fervent emotionalism and dramatic tension matched only by the late sculpture of Giovanni Pisano. |

At Avignon, Simone and the poet-humanist Petrarch formed a close friendship. The painter executed a frontispiece for Petrarch's copy of Commentaries on Virgil, and the poet records in one of his sonnets that Simone painted a portrait, now lost, of his beloved Laura.

Simone's late work at Avignon brings him in close contact with the international traffic of the papal court. His chief works there are the badly damaged fscos representing the battle of St. George with the dragon, a fragment of the Saviour with angels in the narthex, and a fragment representing the Virgin with the kneeling Cardinal Stefaneschi, all in Notre Dame des Domes in Avignon. Possible variations of the spacious St. George composition may be found in a drawing of the Vatican Library and miniatures of the St. George Codex in the archives of St. Peter's in Rome.[2] Simone's further connection with miniature painting may be inferred from the miniature which he is said by Petrarch to have painted in the poet's copy of Virgil, now in the Ambrosian Library of Milan.

|

| [1] Simone Martini (c. 1284–1344) was an Italian painter born in Siena. He was a major figure in the development of early Italian painting and greatly influenced the development of the International Gothic style. It is thought that Martini was a pupil of Duccio di Buoninsegna, the leading Sienese painter of his time. According to late Renaissance art biographer Giorgio Vasari, Simone was instead a pupil of Giotto di Bondone, with whom he went to Rome to paint at the Old St. Peter's Basilica, Giotto also executing a mosaic there. Martini's brother-in-law was the artist Lippo Memmi. Very little documentation survives regarding Simone's life, and many attributions are debated by art historians. Simone was doubtlessly apprenticed from an early age, as would have been the normal practice. Among his first documented works is the Maestà of 1315 in the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena. A copy of the work, executed shortly thereafter by Lippo Memmi in San Gimignano, testifies to the enduring influence Simone's prototypes would have on other artists throughout the 14th century. Perpetuating the Sienese tradition, Simone's style contrasted with the sobriety and monumentality of Florentine art, and is noted for its soft, stylized, decorative features, sinuosity of line, and courtly elegance. Simone's art owes much to French manuscript illumination and ivory carving: examples of such art were brought to Siena in the fourteenth century by means of the Via Francigena, a main pilgrimage and trade route from Northern Europe to Rome. Simone's other major works include the St. Louis of Toulouse Crowning the King at the Museo di Capodimonte in Naples (1317), the Saint Catherine of Alexandria Polyptych in Pisa (1319) and the Annunciation with St. Margaret and St. Ansanus at the Uffizi in Florence (1333), as well as frescoes in the San Martino Chapel in the lower church of the Basilica of San Francesco d'Assisi. Francis Petrarch became a friend of Simone's while in Avignon, and two of Petrarch's sonnets (Canzoniere 96 and 130) make reference to a portrait of Laura de Noves that Simone supposedly painted for the poet (according to Vasari). A Christ Discovered in the Temple (1342) is in the collections of Liverpool's Walker Art Gallery. Simone Martini died while in the service of the Papal court at Avignon in 1344. |

Giorgio Vasari, Simone Martini |

|||

[2] The fresco was painted between Simone's arrival in Avignon sometime between I336 and I340, and his death in that city in 1344. He painted the St. George fresco on the south wall of the porch of Notre Dame-des-Doms and a Virgin and Child with Angels (and Donor) in the tympanum with Christ in Glory above. |

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Podere Santa Pia |

Podere Santa Pia, view from the garden on the valley below |

Siena, Palio |

||

| Famous cyoress road near Montichiello | Castell'Azarra |

|||

|

||||

Podere Santa Pia, situated in a particularly scenic valley, which overlooks on the hills around Cinigiano, up to the Maremma seashore and Monte Christo |

||||

| Francesco Petrarca |

||||

Thanks to Petrarch's sonnets we know that the poet and the painter became very good friends. Simone must undoubtedly have been influenced by the proto-Humanist cultural world of Petrarch, and we can see clearly how the manuscript illumination of Petrarch's Virgil in the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan, with its classical and naturalistic overtones (sophisticated gestures, white cloth drapery, the delicate figures of the shepherd and the peasant), anticipates the typical style of early 15th-century French manuscript illumination.

|

||||

San Gimignano |

The abbey of Sant'Antimo |

Crete Senesi, surroundings of Podere Santa Pia |

||