|

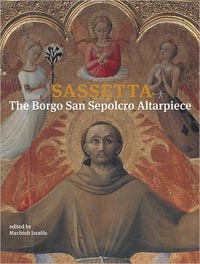

Sassetta, San Sepolcro Altarpiece, 1437-44, Musée du Louvre, Paris

|

|

The Borgo San Sepolcro altarpiece was one of the largest and most splendid altarpieces of the early Italian Renaissance. Six meters wide and five meters high, painted on both sides like Duccio's Maestà in Siena, and made up of sixty images, it was created in 1437-1444 by the crown prince of Sienese painters, Stefano, the son of Giovanni of Cortona, whom we know by the eighteenthcentury nickname Sassetta. |

||

| Bernhard Berenson, A.B. 1887, and his wife, Mary, found the panel in 1900 in a Florence antique shop — a tiny “out-of-the-way hole-and-corner sort of place,” said Mary—just as they were furnishing their newly acquired home, I Tatti. 'The discovery of three panels of this altarpiece by Bernhard and Mary Berenson in a Florentine antique shop on 27 October 1900 was only one episode in the work's dispersal, but it marked the beginning of Sassetta's recovery in scholarship. Sleuthing, especially by Mary Berenson, led the couple to suppose that their panels, showing the Blessed Ranieri, Saint Francis in Glory, and Saint John the Baptist, were the front of a double-sided triptych. The eight scenes of the life of Saint Francis that they had located in three French collections would, they surmised, have constituted the back.' Bernhard Berenson, who became famous as a connoisseur of the “Old Masters” and an arbiter of taste, died 50 years ago at 94. He gave I Tatti to Harvard, along with its gardens, olive groves, and vineyards, his library of 50,000 books (now much enlarged), his photographs (now numbering 300,000), and about 140 works of Italian Renaissance art. The villa opened as a study center in 1961. Today, 15 fellows come for a full year and 20 more for shorter periods. One recent fellow was Machtelt Israëls, an art historian from the University of Amsterdam. She cast a speculative eye on these Sassetta panels. |

||

| Commissioned from Sassetta in 1437 by the monks of the monastery of San Francesco at Borgo Sansepolcro in Tuscany, and installed in their church over the tomb of the Blessed Ranieri Rasini (d. 1304) in 1444, this double-sided altarpiece originally comprised sixty panels. Half of these have survived and are to be found in private collections and museums in Settignano (near Florence), London, New York, Berlin, Chantilly, Cleveland, Moscow, Detroit, and elsewhere. In memory of the Blessed Ranieri Rasini, a native of their town, the monks of the monastery of San Francesco at Borgo Sansepolcro decided in 1437 to call on Sassetta, the most highly reputed of Siena's artists, to create a multipanel, double-sided altar piece, or polyptych. Painted in 1437-44, the work was made up of sixty panels, thirty of which have been identified in public and private collections around the world. The dismantling of Sassetta's masterpiece began in the Counter Reformation. The altarpiece was removed from the high altar and the individual panels were mounted on other altars in the church. The process accelerated after the Napoleonic suppression of convents and religious orders in the first decade of the nineteenth century, when the panels were sold, sawn down the middle to separate fronts from backs, and dispersed, at first to local collections around Arezzo and Siena, then to Florence, then further afield to France, and finally, as Sassetta's fame grew, to museums in the United States, Britain, Germany, and Russia. (...) Even if the dispersal of Sassetta's panels can never be reversed, the Borgo San Sepolcro altarpiece can be reconstructed virtually. Although this has been the ambition of art historians ever since the Berensons in 1903, reconstruction of the panels based on more than aesthetic speculation and piecemeal technical insight became possible only in 1991, with the discovery by James Banker of the scripta, a set of detailed instructions drawn up for the painter by his Franciscan patrons. This precious document, when interpreted by the historian of religion and the art historian working together, held the promise of seeing the altarpiece, at least on paper, whole and entire.' Reconstructed Sassetta altarpiece | Harvard Magazine Nov-Dec 2009 | View illustrations of the altarpiece reconstruction |

||

The Madonna and Child Surrounded by Six Angels, St. Anthony of Padua, St. John the Evangelist

|

||

The Madonna and Child Surrounded by Six Angels occupied the central panel, facing the faithful in the nave and flanked by images of four saints: John the Evangelist, Anthony of Padua, the Blessed Ranieri Rasini, and John the Baptist. Below them the predella comprised scenes from the Passion. On the back of the polyptych an image of St. Francis, the monks' patron saint, was set amid eight episodes from his life. The scenes are 'Saint Francis meets a knight poorer than himself and Saint Francis's vision of the founding of the Franciscan Order'; 'Saint Francis renounces his Earthly Father'; 'Saint Francis before the Pope: The Granting of the Indulgence of the Portiuncola'; 'Saint Francis before the Sultan'; 'The Wolf of Gubbio' (the only scene not based on the 'Legenda Maior', but on the 'Fioretti', or 'Little Flowers of Saint Francis'); 'The Stigmatisation of Saint Francis'; and 'The Funeral of Saint Francis and Verification of the Stigmata'. |

||

| As far as its original appearance can now be reconstructed, this great Franciscan altarpiece, like Duccio's Maestà in Siena Cathedral, showed the Madonna and Child enthroned in the front main tier facing the congregation in the nave. The back, facing the friars in the choir, depicted Saint Francis Triumphant standing on Insubordination, Luxury and Avarice and surrounded by eight smaller scenes from his life ranged in two tiers on either side. Seven of these scenes are now in the National Gallery of London. The panel on the right is one of the best preserved. It shows one of the key events of Francis's life, cited in the process of his canonisation: the impression on his body of the five wounds of Christ. The miracle occurred on 14 September 1224 on La Verna. This forest-covered mountain near Arezzo, where he founded an eremetical convent, had been given to Francis in 1213. It is still a site of pilgrimage. There are many textual sources for Francis's biography. Sassetta, however, almost certainly based his interpretation on artistic tradition. For example, the saint was alone when Christ appeared to him, but it had become customary in painting and sculpture to show his follower Brother Leo witnessing the event, as he is doing here, looking up in wonder from his book of devotions. Giotto had already depicted Saint Francis in the same pose, kneeling and raising his arms to the six-winged seraph-Christ. Sassetta is in many ways a paradoxical painter. Like Giovanni di Paolo and all other Sienese artists, he was deeply in thrall to his great Sienese predecessors of the fourteenth century, the followers of Duccio. He had studied Florentine art of the same period as well as of his own time. Around 1432 he became acquainted with French and northern Italian miniatures. Something of all these sources is evident here, in the ornamental forms of the trees, the unrealistic ledge-like rocks of the foreground and the oblique angle at which he sets the chapel nestling in the mountain - a fourteenth-century method of suggesting perspective. At the same time as Sassetta emulated the decorative effects of archaic styles, he could not help but be influenced by the artistic advances of his day. Thus the supernatural light flooding La Verna from the seraph is virtually consistent throughout the painting. Mountain shadows darken the stuccoed façade of the chapel, with its Virgin and Child above the door; Saint Francis's cord belt casts a shadow on his habit, and his parted fingers on the ground behind his shoulder. The miracle - which has caused the wooden cross in the makeshift oratory to bleed and makes of Francis an 'alter Christus,' a second Christ - is felt throughout the natural world, a red sunset staining the Umbrian hills. |

The Stigmatisation of Saint Francis, National Gallery, London |

|

|

||

Sassetta, The blessed Ranieri frees the poors from a Florentine jail, San Sepolcro Altarpiece, 1437-44, Musée du Louvre, Paris |

||

| The predella recounts the life of Rasini. The Borgo Sansepolcro altarpiece was the most important single commission any artist had yet received in Sansepolcro and the total cost - an incredible 510 florins - remained unsurpassed anywhere in Italy during the fifteenth century. The extravagant outlay was occasioned by the fact that beneath the High Altar was buried the Blessed Ranieri Rasini, a Franciscan lay brother who had become the object of intense local cult in the years following his death in 1304. The decision to award the commission to the greatest living Sienese painter came after an abortive, more modest plan. In 1426 a carpenter by the name of Barolomeo di Giovannino d'Angelo was employed to construct a polyptych on the model of an altarpiece painted three-quarters of a century earlier for the Badia at Sansepolcro, except that the San Francesco altarpiece was to be painted on both the front and back. Work proceeded slowly, and only in 1430 was a local artist, Antonio di Giovanni d'Anghiari, engaged to paint the front of the completed structure. Work progressed no farther than the preparation of the panels with a coat of gesso, and in 1437 the superintendents of San Francesco, Cristoforo di Francesco di Ser Feo and Andrea di Giovanni di Tano, approached Sassetta with the task. Borgo Sansepolcro had longstanding political - it only became Florentine territory in 1441 - and cultural ties with Siena. Moreover, just two or three years earlier Sassetta had completed an altarpiece in nearby Cortona, providing a demonstration of his capabilities. It was probably with that work in mind that, on 5 September 1437, Master Stefano di Giovanni [Sassetta] was engaged 'to make and construct a wooden altarpiece for the high altar of the said church of San Francesco... similar to that altarpiece already constructed and gessoed... [and] to paint it on both sides... with those stories and figures as shall be established by the superior and friars of the said place of San Francesco.' In other words, the work executed between 1426 and 1430 was to be abandoned, and Sassetta was to begin afresh. The altarpiece was to be completed within four years, at which time Sassetta agreed to personally supervise its transport from Siena, oversee the assembly of the individual panels in the superstructure and their installation in the church, and make any necessary repairs. Four years may seem a generous period of time, but the friars had already waited ten, and the work was of an exceptional complexity. Moreover, Sassetta's elaborate technique, with its use of tooled gilt surfaces glazed with color, entailed a slow rate of production. In the end, work dragged on for seven years, and only on 5 June 1444 did Sassetta receive his final payment. [3] |

||

| This altarpiece was a large, double-sided Gothic polyptych of exceptional complexity and richness, so carefully conceived that it is impossible to ascribe any of the surviving fragments to studio assistants. Throughout, it is Sassetta's mind and hand that predominates. This is true of the present Saint Augustine, shown wearing a bishop's mitre and cope over a black habit with a pile of books: attributes of his status as Bishop of Hippo; as author of the Rule of the Augustinian Canons; and as one of the Four Doctors of the Latin Church. In conformity with his high original position above the main panel of the Altarpiece, he is depicted from below, as if seen through a lanceolate window over which the books project. His sensitively drawn features are especially notable for the irises of the eyes, which have the appearance of foreshortened discs, and the beautiful curve of the ear, pressed down by the jewelled mitre. No less notable is the way Sassetta has carefully calculated the saint's silhouette so that it echoes the shape of the frame, the mitre filling the pointed upper portion, while the shoulders expand to fill the curve of the lower arch. Typical of Sassetta's refined execution is the use of metal leaf tooled with small striations and then glazed over with color to suggest the velvet of the cope. This is a highly fragile technique that only rarely escapes damage; the judicious restoration of this panel suggests its original beauty. [3] | ||

| Sassetta: The Borgo San Sepolcro Altarpiece, by Machtelt Israels (Editor), James R. Banker (Contributions by), Rachel Billinge (Contributions by), Roberto Bellucci (Contributions by), 2009, Florence & Leiden, Villa I Tatti/ The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies/ Primavera Press. Machtelt Israëls is Researcher in the History of Renaissance and Early Modern Art at the University of Amsterdam. Admirers of the richness, seductive accents and elusive beauty of the paintings of Stefano di Giovanni, known as il Sassetta , will be delighted by the extraordinary, indeed exhaustive depth of this two-volume study devoted to the polyptych once to be seen on the high altar of the church of S. Francesco in Borgo San Sepolcro. Synopsis |

|

|

| Reconstructed Sassetta altarpiece | Harvard Magazine Nov-Dec 2009 | Christopher Reed, Masterpiece Pieces, 'Investigators construct a virtual fifteenth-century altarpiece 'The dismantling of this masterpiece for liturgical reasons occurred between 1578 and 1583. Today only 27 of its paintings are known to exist, in 12 museums. But Israëls conceived the notion that the altarpiece could be reconstructed in a different medium because Sassetta’s patrons had given him a scripta, detailed instructions, a document discovered in 1991. Israëls assembled a team of 30 experts—in art and general history, painting technique and conservation, woodworking, architecture, and liturgy, including all scholars studying the artist—from eight countries. They have now produced Sassetta: The Borgo San Sepolcro Altarpiece, a richly illustrated book edited by Israëls, just published by I Tatti, and distributed by Harvard University Press. Thanks to this remarkable collaboration, what Dutch art historian Henk van Os has called the Rolls-Royce of early Italian Renaissance altarpieces is virtually together again—and gleams.' Reconstructed Sassetta altarpiece | Harvard Magazine Nov-Dec 2009 | View illustrations of the altarpiece reconstruction |

||

|

||||

Podere Santa Pia |

Podere Santa Pia, view from the garden on the valley below |

Podere Santa Pia, view onthe house and some of the old oaks in the garden

|

||

Tombolo di Feniglia |

Crete Senesi, Asciano |

L'eremo di Montesiepi (the Hermitage of Montesiepi) |

||

Situated at the intersection of the Valdarno, the Valdichiana and the Casentino, Arezzo is a town in south-eastern Tuscan that has maintained its Medieval structure. The Basilica di San Francesco is the most important monument of this city so rich in places to interest, such as the Cathedral and the Pieve di Santa Maria. The church houses the "Legend of the True Cross", the famous cycle of frescoes by Piero della Francesca.

|

||||

|

||||

| Situated in a charming position on the top of a smooth hillside, Podere Santa Pia offers an extensive view of a breathtaking panorama all the way to the sea. The beautifully situated terrace has views over what seems like half of southern Tuscany. On clear days you can have a great view of the islands of Monte Argentario, Elba and even Corsica. |

||||

[1] Together with Florence, Siena was the chief economic, political, and cultural center of Tuscany in the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance. Although only in 1559 did Siena become part of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany under the rule of the Medici, its heyday was unquestionably two centuries earlier, between 1287 and 1355, when the independent commune was ruled by nine magistrates (referred to as the nove) drawn from a restricted oligarchy. During this time of peace and prosperity—interrupted by the devastating plague of 1348 that reduced the population by more than half—the city allied itself with the papal party of the Guelphs and had contacts with the Angevin dynasty in France and Naples. These political ties help explain the pronouncedly Gothic character of so much Sienese architecture and the fluent elegance of its paintings. No other city outside Florence produced a comparably great school of painting, culminating in the figures of Duccio di Buoninsegna (active by 1278, died 1318), Simone Martini (active by 1315, died 1344), and the brothers Pietro and Ambrogio Lorenzetti (active 1320–44, 1319–47, respectively). Outstanding artists such as Sassetta, Giovanni di Paolo, Neroccio de' Landi (61.43), Matteo di Giovanni, and Beccafumi maintained the great tradition established by their fourteenth-century forebears. A wind of change and a more complex type of culture entered Sienese painting with the polyptych done in 1423-26 for the "Arte della Lana" (the Wool Guild). The artist was Stefano di Giovanni, later to be known as Sassetta. All that remains of this work consists of a side-panel in the collection of the Monte dei Paschi Bank in Siena, the predella now distributed among the Pinacoteca, the Budapest Museum, the Vatican Pinacoteca, the Bowes Museum at Barnard Castle and the Museum of Melbourne, along with a few other minor but significant fragments. Sassetta, whose date of birth is unknown, here shows that he was in touch with all the most recent tendencies of European late-Gothic (which probably came to him by way of the exquisite painting of Masolino da Panicale), while at the same time he went further with the Lorenzetti's intuitions of space, adding realistic features unknown to the previous tradition. [2] Sassetta (1392 - 1450), Stefano di Giovanni. Around 1400, Stefano di Giovanni, now known as Sassetta, was born a servant's son in the town of Cortona, overlooking Lake Trasimeno in eastern Tuscany.33 When he was still a youngster, his family moved to Siena, where he was trained probably in the late-gothic tradition of Benedetto di Bindo (d. 1417) and Andrea di Bartolo (d. 1428). At a decisive moment in his career, at the time of his very first documented commission, for the Sienese Wool Guild, he succumbed to the spell of refined and famous Gentile da Fabriano (d. 1427), then at work in Siena. The date and birthplace of Sassetta are not known. He was probably born in the last decade of the fourteenth century, and since his father, Giovanni, is called "da Cortona," Cortona might have been the artist's birthplace. The meaning of his nickname, "Sassetta," is obscure; it is not cited in documents of his time, but begins to appear in sources in the eighteenth century. One of the most important figures of Sienese early Renaissance painting, Stefano was probably trained alongside artists like Benedetto di Bindo and Gregorio di Cecco, but revealed from the beginning an orientation completely different from the late Gothic style that dominated his city in the first decades of quattrocento. His first certain work, which originally bore his signature, is the Arte della Lana altarpiece (1423-1426, fragments are now divided among various public and private collections). Its quality demonstrates that by this time he had already achieved a very high level of technical refinement and poetic invention, and it testifies to his awareness of the artistic innovations developed in Florence by Gentile da Fabriano, Masolino, and others of his generation. These tendencies are even more evident in his second prestigious commission, the Madonna of the Snow altarpiece, painted between 1430 and 1432 for the Siena cathedral (now in the Palazzo Pitti, Florence, Contini Bonacossi bequest): Sienese tradition is here brought up to date with results of an arcane splendor, where the abstract solemnity of the figures is infused with a limpid natural light that molds the forms and frames the daring perspectival passages with a coherence foreshadowing the art of Piero della Francesca. Numerous other works that testify to Sassetta's fame in Siena can be gathered around these two great undertakings: the painted Crucifix for the church of San Martino in 1433 (there survive today only three fragments with the two mourners and Saint Martin Sharing His Cloak with a Beggar, in the Chigi-Saracini collection in Siena); various images of the Madonna and Child (Pinacoteca Vaticana, Rome; Gemäldegalerie, Berlin; Museo Amedeo Lia, La Spezia), as well as a polyptych painted for the church of San Domenico in Cortona (Museo Diocesano, Cortona). Between 1437 and 1444, the artist took part in the execution of the large two-sided altarpiece for the church of San Francesco in Sansepolcro. Besides the Madonnas in Siena (Pinacoteca Nazionale, no. 325) and Grosseto (Museo Diocesano), one of Sassetta's last endeavors was a fresco of the Coronation of the Virgin on the Porta Romana in Siena, begun in 1447 and interrupted by his death in 1450. It was finished by Sano di Pietro, who also brought to completion the polyptych for San Pietro alle Scale, for which Sassetta had only managed to paint one element (Saint Bartholomew, Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena, no. 240). National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC | www.nga.gov | The artist's biography published in the NGA Systematic Catalogue [3] 'This altarpiece was a large, double-sided Gothic polyptych of exceptional complexity and richness, so carefully conceived that it is impossible to ascribe any of the surviving fragments to studio assistants. Throughout, it is Sassetta's mind and hand that predominates. This is true of the present Saint Augustine, shown wearing a bishop's mitre and cope over a black habit with a pile of books: attributes of his status as Bishop of Hippo; as author of the Rule of the Augustinian Canons; and as one of the Four Doctors of the Latin Church. In conformity with his high original position above the main panel of the Altarpiece, he is depicted from below, as if seen through a lanceolate window over which the books project. His sensitively drawn features are especially notable for the irises of the eyes, which have the appearance of foreshortened discs, and the beautiful curve of the ear, pressed down by the jewelled mitre. No less notable is the way Sassetta has carefully calculated the saint's silhouette so that it echoes the shape of the frame, the mitre filling the pointed upper portion, while the shoulders expand to fill the curve of the lower arch. Typical of Sassetta's refined execution is the use of metal leaf tooled with small striations and then glazed over with color to suggest the velvet of the cope. This is a highly fragile technique that only rarely escapes damage; the judicious restoration of this panel suggests its original beauty. Sassetta (the name is found in no contemporary documents and seems to have been first applied to the artist in the eighteenth century) was unquestionably the most original Sienese painter of the first half of the fifteenth century. Although much of his work (designs for stained-glass windows, painted banners and illuminations) is now lost, his reputation rests on three extraordinary altarpieces: the Arte della Lana of 1423 (mostly Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena); the Madonna of the Snow, painted between 1430 and 1432 (Contini-Bonacossi Bequest, Florence) and the Borgo Sansepolcro Altarpiece, completed in 1444. He was an artist of remarkable range and intellectual curiosity. He seems to have visited Florence where the naturalism of Masaccio and Masolino's frescoes in the Brancacci Chapel exerted an influence on the Madonna of the Snow. At the same time he would have seen Gentile da Fabriano's masterpiece, the Adoration of the Magi, whose charming narrative detail and ornate surface were to change the direction of the Sienese artist's stylistic development. Sassetta's natural inclination was to work at ingenious solutions to the convincing depiction of space within the limitations imposed by the formal gothic altarpiece, as well as to explore the expressive possibilities of exquisitely wrought surfaces and the graceful curvilinear forms of the gothic tradition - a tradition exemplified by his Sienese forbears Pietro and Ambrogio Lorenzetti. While clearly aware of developments in Florence, Sassetta's genius lies in the originality with which he breathed new life into the gothic idiom and inspired a generation of remarkable Sienese artists, among them Sano di Pietro, The Osservanza Master and Vecchietta. The Borgo Sansepolcro altarpiece was the most important single commission any artist had yet received in Sansepolcro and the total cost - an incredible 510 florins - remained unsurpassed anywhere in Italy during the fifteenth century. The extravagant outlay was occasioned by the fact that beneath the High Altar was buried the Blessed Ranieri Rasini, a Franciscan lay brother who had become the object of intense local cult in the years following his death in 1304. The decision to award the commission to the greatest living Sienese painter came after an abortive, more modest plan. In 1426 a carpenter by the name of Barolomeo di Giovannino d'Angelo was employed to construct a polyptych on the model of an altarpiece painted three-quarters of a century earlier for the Badia at Sansepolcro, except that the San Francesco altarpiece was to be painted on both the front and back. Work proceeded slowly, and only in 1430 was a local artist, Antonio di Giovanni d'Anghiari, engaged to paint the front of the completed structure. Work progressed no farther than the preparation of the panels with a coat of gesso, and in 1437 the superintendents of San Francesco, Cristoforo di Francesco di Ser Feo and Andrea di Giovanni di Tano, approached Sassetta with the task. Borgo Sansepolcro had longstanding political - it only became Florentine territory in 1441 - and cultural ties with Siena. Moreover, just two or three years earlier Sassetta had completed an altarpiece in nearby Cortona, providing a demonstration of his capabilities. It was probably with that work in mind that, on 5 September 1437, Master Stefano di Giovanni [Sassetta] was engaged 'to make and construct a wooden altarpiece for the high altar of the said church of San Francesco... similar to that altarpiece already constructed and gessoed... [and] to paint it on both sides... with those stories and figures as shall be established by the superior and friars of the said place of San Francesco.' In other words, the work executed between 1426 and 1430 was to be abandoned, and Sassetta was to begin afresh. The altarpiece was to be completed within four years, at which time Sassetta agreed to personally supervise its transport from Siena, oversee the assembly of the individual panels in the superstructure and their installation in the church, and make any necessary repairs. Four years may seem a generous period of time, but the friars had already waited ten, and the work was of an exceptional complexity. Moreover, Sassetta's elaborate technique, with its use of tooled gilt surfaces glazed with color, entailed a slow rate of production. In the end, work dragged on for seven years, and only on 5 June 1444 did Sassetta receive his final payment. Curiously, despite the ample documentation relating to the commissioning of the altarpiece, no description of it in situ survives. Between 1578 and 1583 it was removed from the High Altar to make way for a tabernacle, in conformity with liturgical demands following the Council of Trent. The polyptych seems to have been dismembered and the individual panels distributed throughout the church. In 1583 two lateral panels, showing Saints John the Evangelist and Anthony of Padua, decorated one altar, the center panel of the Madonna and Child with angels another, while a panel of the Blessed Ranieri Rasini hung in the choir until 1752. Minor parts of the altarpiece may well have been sold off or salvaged for their wood. In 1810, following the Napoleonic suppression of religious Orders, the main panels were purchased by a Cavalier Sergiuliani of Arezzo, who presented them to the Canon Angelucci. In turn, Angelucci gave them to his brother, and it was in a small church in Monte Contieri, near Asciano, that in 1823 the Sienese writer, E. Romagnoli, recorded the existence of 'two panels painted in tempera, in the first of which is shown Saint Francis with open arms, in the second the Virgin and Child and various angels. To the same altarpiece belong four vertical panels with various saints, all well preserved'. This is the first mention of the sublime Saint Francis in Glory which was part of the Borgo Sansepolcro Altarpiece, and purchased for I Tatti, as well as the Madonna and Child rediscovered in France in 1951 and acquired by the Louvre. The panels with Saints John the Baptist, John the Evangelist, Anthony of Padua, and the Blessed Ranieri Rasini are now divided between the two institutions. In 1839 G. Rosini recorded that below the Saint Francis ran an inscription commemorating the role played by the two superintendents who had commissioned the altarpiece: 'CRISTOFORUS FRANCISCI FEI ANDREAS IOHANNIS TANIS OPERARIUS A. MCCCCXXXXIIII'. He also mentioned the existence of eight panels with scenes from the Life of Saint Francis, obviously those now in the National Gallery, London, and in the Musée Condé, Chantilly. Several other panels can be confidently associated with the altarpiece on grounds of style, subject, or the decoration of their frames. Among these are three predella panels, showing Miracles of the Blessed Ranieri Rasini and first described by Giovanni Battista Castiglione, a Milanese priest, in 1622. Two of them are in the Louvre - one being rediscovered and purchased only a year ago - and the third is in the Gemäldegalerie, Berlin. Four small upright panels, showing Saint Christopher (the Mason Perkins Collection, the Sacro Convento, Assisi), and Evangelist (formerly in the Cini Collection, Venice), and Saints Lawrence and Stephen (Pushkin Museum, Moscow), that would have flanked the altarpiece as pilasters survive. Saint Francis Adoring the Crucified Christ (Cleveland Museum of Art); The Annunciation (Robert Lehman Collection, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York); and the present Saint Augustine, would have formed pinnacles. In reconstructing the appearance of Sassetta's altarpiece it must be borne in mind that the two sides addressed different audiences and that the pictorial content of the main side facing the nave was necessarily more conventional than that of the reverse towards the choir. The front had, at its center, the Madonna and Child enthroned before a symbolic rose hedge with, to either side, three angels, two of whom suspend a crown over the Virgin's head. This panel was flanked by depictions of the Blessed Ranieri Rasini and Saints John the Baptist, John the Evangelist, and Anthony of Padua. Two of these figures are Franciscans, one a native of Sansepolcro and the other second in popularity only to Francis himself; while Saint John the Evangelist was of special importance to the Order, in that his apocalyptic vision in the Book of Revelations had come to be applied to Saint Francis by the Franciscan followers of Joachim of Fiore. In accordance with common practice, the pinnacle with the Annunciation would have stood above the Madonna and Child, while the scenes with the Miracles of the Blessed Ranieri Rasini would have adorned the predella in commemoration of his burial beneath the altar of the church. Whether the remaining scenes showed further miracles of his life or depicted events in the life of Saint Anthony of Padua cannot be said. Facing the monks' choir would have been the depiction of Saint Francis surrounded by cherubim, his outstretched hands and feet marked by the stigmata, borne over a seemingly limitless sea on the backs of allegorical figures of Insubordination, Luxury, and Avarice. This extraordinary image, which Berenson thought without peer in Western art, is a unique visualization of Saint John the Evangelist's vision after the opening of the Sixth Seal: 'And I saw another angel ascending from the east, having the seal of the living God' (Revelations 7, 2). Saint Bonaventura cites the passage in his official Life of Saint Francis, applying its imagery to Saint Francis and explaining that the seal of the living God is the stigmata Saint Francis bore. Around the saint's halo runs the inscription, 'PATRIARCHA PAUPERUM FRANCISCHUS' (Francis the Patriarch of Poverty). Poverty was, of course, the cardinal virtue of Saint Francis, and is so noted by Dante in the Paradiso. To either side of this mystical figure, eight panels encapsulating the life of Saint Francis were arranged in two tiers, the order of which has only recently been established. Above the center panel would have stood the Cleveland pinnacle of Saint Francis Adoring the Crucified Christ whose wounds he bore. There is no firm indication for the subjects of the predella, but the idea of Francis as a second Christ (Franciscus alter Christus) that is alluded to in the center panel and its pinnacle suggests that the three predella scenes from Christ's Passion, now in the Detroit Institute of Art, may have belonged to the altarpiece. S. Beguin has reasoned that pilaster panels showing the patron saints of the two superintendents, whose names were inscribed below the Saint Francis, adorned the reverse of the altarpiece. One of these would have been the Mason Perkins Saint Christopher. The Pushkin panels with Saints Lawrence and Stephen, as well as one with Saint Vincent, may also have been included, as Saint Bernardine had declared them co-partriarchs with Saint Francis. The pinnacle with Saint Augustine could have belonged to either the front or the back, possibly accompanied by the other Doctors of the Latin Church: Saints Gregory the Great; Jerome; and Saint Ambrose. Sassetta's altarpiece was unquestionably the most sumptuous and elaborate work to have been produced since the completion of Duccio's Maestà in 1311, and it was to remain the greatest masterpiece of fifteenth-century Sienese painting, combining delicacy of feeling with decorative splendour, and effulgent surfaces with nuanced effects of light and atmosphere. In his classic study of the altarpiece, Berenson emphasized the calligraphic character of Sassetta's line, but to comtemporaries it was not this residual Gothicism that seemed remarkable but rather Sassetta's exquisite sensitivity to the visual world - whether the miraculous aura of light surrounding the figure of Christ in Saint Francis Receiving the Stigmata (National Gallery, London), the penumbral interior of a conventional church with monks seated in rustic stalls in the recently rediscovered Miracle of the Miser of Citerna (Louvre, Paris), or the transparency of the southern Tuscan sky against the profile of Monte Amiata in The Mystic Marriage of Saint Francis of Povery (Musée Condé, Chantilly). In the predella of his earliest work, the altarpiece painted between 1423 and 1426 for the Guild of the Arte della Lana, Sassetta revealed a precocious talent in this direction, minutely recreating a medieval library and depicting some of the earliest naturalistic skies in Italian art. Under the influence of Masaccio, whose work he saw on an undocumented trip to Florence about 1430, this visual awareness acquired weight and expressive force. In the narrative panels of the Borgo Sansepolcro Altarpiece, the more realistic features of this Masaccesque phase have been refined in the fire of Sieneses traditions - especially that of Simone Martini - and have emerged purified of any gross traits. Sassetta shared with his great Florentine contemporaries an interest in geometric forms: the pattern created by a beamed ceiling; the arc described by a flock of cranes; or the trapezoidal shape of the sides of a marble throne viewed in steep foreshortening. He was, however, more interested in these for their aesthetic properties than as a means of analyzing the visual world. Indeed, much of the iconic power of the image of Saint Francis in Glory derives from the simple, abstract shape of his girdled habit and foreshortened head. Similarly, the deep landscape behind the figures in The Mystic Marriage of Saint Francis to Poverty is composed of a patchwork quilt of rectangular, colored fields, less regular than those employed by Uccello but for that very reason more truthful and convincing. This emphasis on geometric purity seems even to have impressed the young Piero della Francesca, who must have watched the installation of the polyptych with a mixture of perplexity and admiration. Piero had returned to Borgo Sansepolcro from Florence by June 1442, and three years later was commissioned by the Compagnia della Misericordia to paint a polyptych with, at its center, a Madonna of Mercy. It has long been recognized that this majestic and solemn figure is, to a certain extent, based on Sassetta's image of Saint Francis. However, Piero illuminated his figure with a focused light that both models and measures its volume, while Sassetta has enveloped his with a diaphanous light of beaten gold. Similarly, the landscape in Piero's Baptism of Christ (National Gallery, London) - which is sometimes thought to preceed the completion of Sassetta's altarpiece but is likely to have been executed about 1450 - utilizes some of the devices employed by Sassetta in his scene of Saint Francis' mystic marriage, but with a mathematical and optical exactitude that is worlds apart. It is in comparison with these masterpieces of Renaissance painting that Sassetta takes his place as the last great representative of Sienese Gothic painting.' Source | www.christies.com | 'Stefano di Giovanni, called Sassetta (Siena 1395-1450), Saint Augustine, a pinnacle of the Borgo Sansepolcro Altarpiece'. |

||||

This page uses material from the Wikipedia article Stefano di Giovanni published under the GNU Free Documentation License. |

||||

|

||||

| Arezzo | Sansepolcro |

Sunsets in Tuscany |

||

Saint Francis renounces his Earthly Father, National Gallery, London

Saint Francis renounces his Earthly Father, National Gallery, London