| |

|

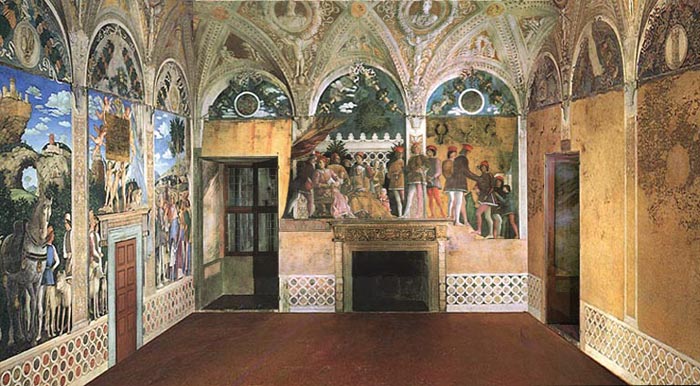

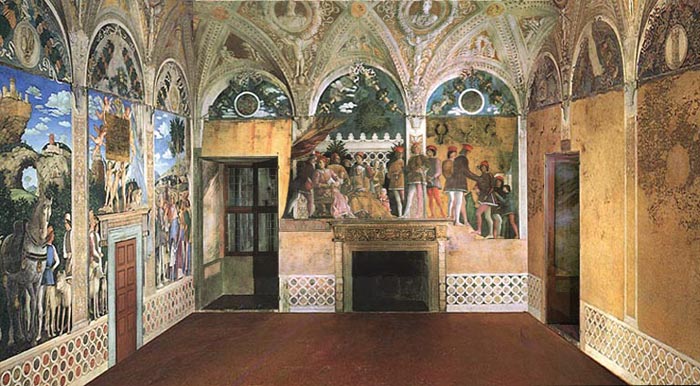

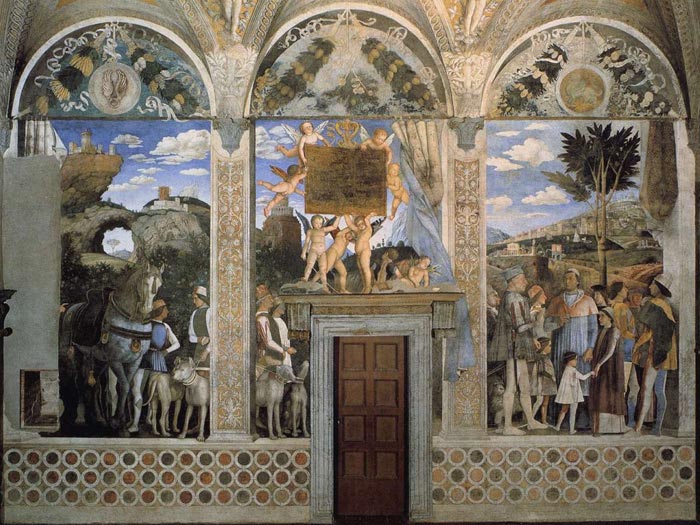

The Camera degli Sposi ("bridal chamber"), sometimes known as the Camera picta ("painted chamber"), is a room frescoed with illusionistic paintings by Andrea Mantegna in the Ducal Palace in Mantua. It was painted between 1465 and 1474 and commissioned by Ludovico Gonzaga, and is notable for the use of trompe l'oeil details and its di sotto in sù ceiling.

Again a mastery of perspective is displayed, but also, in the representations of the Gonzaga family and court, Mantegna's skill as a portraitist. [1]

Ludovico’s principal commission from Mantegna was an historiated portrait gallery for the Palazzo Ducale, Mantua; this mural decoration took the artist nearly ten years to complete. The so-called Camera Picta (1465–74), also known as the Camera degli Sposi, shows the Marchese and his consort, Barbara of Brandenburg, together with their children, friends, courtiers and animals engaged in professional and leisurely pursuits, illustrating the present successes and alluding to the future ambitions of the Gonzaga dynasty. The gallery represents the culmination of a series of secular decorative schemes for palace interiors in northern Italy in the 14th and 15th centuries, and the illusionism of the painted vault establishes its status as the progenitor of Correggio’s ceilings and those of the Baroque. The Camera Picta is a room with a square plan (8.1×8.1 m). An inscription, simulating graffiti, on the embrasure of the north window, 1465.d.16.iunii, indicates the date of the official commencement of the decoration.

The Court Scene on the west wall shows Ludovico Gonzaga, dressed informally, with his wife Barbara of Brandenburg. They are seated with their relatives, while a group of courtiers fill the rest of the wall. The figures interact with an illusionistically expanded space is depicted.

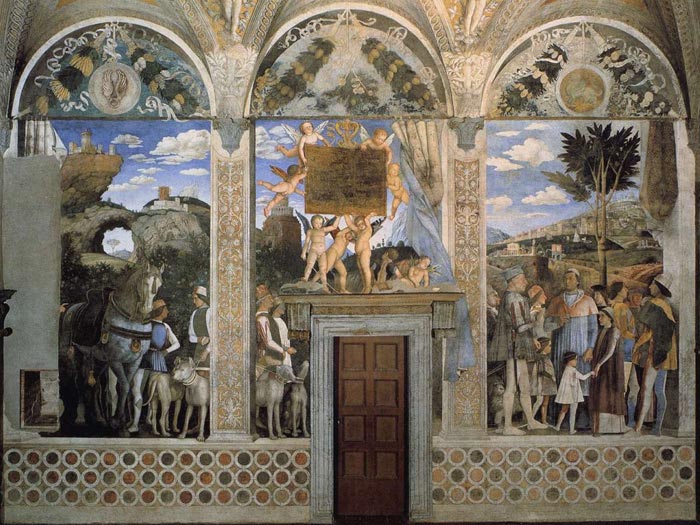

On the north wall is the Meeting scene. This fresco shows Ludovico in official robes in an ideal meeting with his son cardinal Francesco Gonzaga, the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick III and Christian I of Denmark. [2]

Mantegna's playful ceiling presents an oculus that illusionistically opens into a blue sky, with foreshortened putti playfully frolicking around a ballustrade. This was one of the earliest di sotto in sù ceiling paintings.

|

|

Andrea Mantegna, Camera degli Sposi, Palazzo Ducale, Camera degli Sposi (Bridal Chamber), Mantua

|

The architect who carried out the extensive restoration of the hall was the Florentine Luca Fancelli, who was commissioned to transform the military aspect of the castle of San Giorgio (a solid fortress strategically positioned on the river Mincio, built by Bartolino da Novara and completed in 1406) into a sumptuous dwelling for Ludovico Gonzaga. Fancelli, who worked for the Gonzagas from 1450 to 1484, had already worked amicably with Mantegna on the castle chapel, often being dominated by the painter’s personality.

There are few frescoes where the artist could avoid adapting to a pre-existent situation and to place the inclination of the light destined to fall on the work of art. This makes the Camera degli Sposi a place of privileged experience which no description or reproduction can explain. Thanks to the position of the windows, the undecorated walls, that are enclosed in false curtains, seem to provoke an effect of shadows which is, in effect, due to a play of natural light. On the contrary, the pictorial composition emits an illusion of its own light with the substantial difference of luminosity between the northern wall (those of the “Court”) and the one on the west side (with the so-called “meeting”) that has as its background an open panorama and a wide glimpse of sky. The west wall, unlike the one to the north, benefits from a window placed almost in front, and it’s visible in a counter-light, softened by the grazing light from the opening to the east.

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Andrea Mantegna, Marquess Ludovico Greeting His Son Cardinal Francesco Gonzaga, Palazzo Ducale, Camera degli Sposi (Bridal Chamber), Mantua

|

In the Camera degli Sposi it is possible to see the use of mathematical - geometric knowledge with regard to perspective which Mantegna exploited with ease but without the “dry manner” of which Vasari speaks – the exploit of the oculus apart – there remains the more “popular” sign of the Chamber, perhaps a little ignored by the critics. Let us try to return to it later. In his popular History of Art, Gombrich observes with regard to the frescoes of the Storie di San Giacomo, destroyed during a bombing raid, that Mantegna did not use the art of perspective in the same way as Paolo Uccello, who used the new effects to “show off”, but to give a solidity and physical appearance to the characters painted. And to create an architectonic illusion: in the Wedding Chamber the few elements that stand out are the door posts, the fireplace and a small walled cupboard as well as corbels that falsely support the triple lunettes that join the vault of the ceiling to the walls. The rest is painted architecture and this helps us to read the name Camera picta (or even camera magna picta) no longer a simple “room decorated by paintings” but constructed with images and geometry and, in this way, rendered “magna”. i. e. magnificent. The crowd of the court and family on one side, the characters in plein-air and the panorama on the other and finally the vaults that stretch up to the sky creating a truly convincing illusion of being at the centre of a space whose boundaries are those dictated by one’s own visual capacity.

Some details can help us to understand the geometrical and perspective techniques used by Mantegna in the Camera degli Sposi. The mighty horse to the left of the Meeting for example is slanted with lines of escape that do not allow it to enter the scene, towards the observer, but make it appear in the “background” outside the wall on which it is painted. Paccagnini (op. cit., page 69) talks of visual pyramids formed by the composition and the vaults, with convergent vertices to indicate the visual point desired by the artist; in the oculus, formed by a series of concentric circles that diminish in size, a cone that resembles an inside-out telescope can be found, due to the effect of quick withdrawal that it produces. The materially adjacent objects are used to accentuate the illusion: the frame around the fireplace supports the carpet (that, at the end of the shelf, forms a hanging pleat) serves as a surface for the false staircase on which some of the characters stand. The shelf continues along the wall until it supports a character with his back leaning against a column. Another cornice, that of the door on the west side, supports the winged putti, busy – not all of them – holding the bronze scroll (obviously false) with the dedication. The monochrome medallions of the Roman Emperors on the parts on the ceiling, are used in a contrary way. With their false and perfectly deceptive high-relief they “enter” the Chamber to create the illusion of a vault that is sufficiently high to contain the marble busts such as those that the visitor will already have seen as he approached the chamber. Even the relief of the festoons in the lunettes acts as an upside-down pyramid. In this case it contributes to the separation from the vaults or better still from the ceiling.

|

|

West wall - The Meeting

North wall - The Court

East wall

South wall

|

One the most remarkable portions of the decoration of the Camera degli Sposi is the fictive oculus, or opening to the sky, located on the room's low ceiling. Created with sharp foreshortenings, the oculus is ringed with figures looking down on the room below; a potted plant is precariously perched on its wooden support, seemingly ready to fall at any moment. It is a brilliant tour de force that invariably engages the spectator, who must join in the game by standing directly beneath the circular trellis.

Mantegna demonstrated his mastery of trompe l’œil in his depictions of architecture and sculpture (his oculus in the Camera degli Sposi in the Palazzo Ducale in Mantua). He used this painterly artifice here by adding a porphyry frame, acting as an imaginary window onto the picture space. In doing so, he was evoking the theory discussed by Alberti in his De Pictura (1435), according to which the painting is a window on reality. The two executioners, daringly cut off below the shoulders, enhance this illusionist effect, which Mantegna used in other works, including The Crucifixion (INV 368). The viewer is invited to place himself at the same height as the archers, thus adopting their point of view and humbling himself before the sculptural body of the saint towering above him. The very low vanishing point, upward-looking viewpoint and masterful foreshortening imbue the martyr with a solemn monumentality.

|

|

Ceiling

|

|

The famous false opening of the sky on the ceiling, a prototype of a trompe-l’oeil. The magnificent details of the ceiling and some of the busts and scenes stand among the most convincing trompe l'oeil passages of the entire Italian Renaissance

. |

In their attempts to interpret the group portrait on the north (fireplace) wall, commonly referred as La Corte dei Gonzaga (The Court of Gonzaga), a number of scholars have sought to identify it as a specific historical event, much as they have the one on the west wall, conventionally called L'Incontro (The Meeting). However, there is no indication in the paintings themselves that these are crucial events, no hint of their historical significance, something that may have been incorporated into the background. Therefore increasing numbers of scholars have tended to doubt that the pictures represent actual historical events.

The identity of some of the portraits has been clarified based on existing documents. The girls beside the marchesa are her two daughters Paola and Barbara. Ludovico Gonzaga is seated on a chair by the left pilaster. He turns to the side to speak with a man who has just entered from the left. To Gonzaga's right sits his wife, Barbara von Hohenzollern-Brandenburg, surrounded by her sons and daughters, a nurse, and a female dwarf. Beneath the right arcade, which is closed by a curtain that is drawn aside only slightly at the outside corner, stand a number of noblemen in elegant and colourful costumes. This procession of courtiers, identified by the colours of their leggings as adherents of the Gonzaga, is led by a young blond man who, like the presumed secretary at the left edge of the picture, stands in front of the painted pilaster. He is flanked by associates who are in part obscured by the same pilaster. The blond youth with a dagger at his waist was identified as Rodolfo Gonzaga.

Although many scholars tried to identify the figures in the painting, the only ones that can be considered confirmed are those of the marchese's immediate family. |

|

Ludovicio Gonzaga |

|

Mantegna's Camera Degli Sposi, edited by Michele Cordaro ; essays by Maurizio Marabelli, Giovanni Rodella, Giuseppina Vigliano, Milano, Electa, 1993.

Mantegna's Camera Degli Sposi focuses solely on Andrea Mantegna's cleaned and restored fresco decorations for "La Camera Degli Sposi" ("The Wedding Chamber") in Mantua's Palazzo Ducale. These frescoes are major achievements in the art of the Italian Renaissance and influenced all the leading artists of the age. This book examines the technique, iconography and historical interpretation of the fresco cycle, as well as the difficulties of its restoration. Each scene is reproduced in its entirety and in close-up, revealing its myriad details and giving an intimate view of the whole of the room.

Art in Tuscany | Italian Renaissance painting

Camera degli Sposi: mostra di Andrea Mantegna al castello di San Giorgio - Mantova (it) | www.cameradeglisposi.it

Art in Tuscany | Giorgio Vasari's Lives of the Artists | Andrea Mantegna

Giorgio Vasari | Le vite de' più eccellenti architetti, pittori, et scultori italiani, da Cimabue insino a' tempi nostri | Andrea Mantegna

Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Andrea Mantegna, Camera picta - Ceiling and Camera picta - Court.

[1] From 1460 Mantegna was court painter to the Gonzaga rulers of Mantua, his most important work here being the decoration of the Camera degli Sposi (the Bridal Chamber, completed 1474) of the Palazzo Ducale. Again a mastery of perspective is displayed, but also, in the representations of the Gonzaga family and court, Mantegna's skill as a portraitist. Perhaps the most significant part of the scheme is the painting of the ceiling, the middle of which is illusionistically opened up to the sky for the first time since antiquity. From over the fictive balustrade of a circular balcony, figures appear to look down into the room below. Such convincing illusionism was not accomplished again until Raphael in the Vatican and Correggio at Parma before reaching its consummation in the stunning illusionism of l7th century Baroque ceilings in Rome. Also for the Gonzaga family was the series of nine monumental canvases of the Triumphs of Caesar (c 1486, London, Hampton Court) which, in addition to all his usual characteristics, reveal Mantegna's interest in antique bas reliefs. For Isabella d'Este, the wife of Francesco Gonzaga, Mantegna painted the Madonna della Vittoria (1495-6) and the Parnassus (both Paris, Louvre).

Vasari included Andrea Mantegna amongst those who, from Piero della Francesca to Luca Signorelli, had introduced “for the excessive study… a certain dry, crude and cutting manner”: to force themselves, they tried to use the impossibility of art with all its trials and tribulations in the landscapes and views that were, in their turn, difficult to paint, so hard and difficult to see for those who observed them. The scorci (foreshortenings) were the perspectives, with a marked referral by Vasari to those from the bottom to the top.

[2] Ludovico II (or III) of Gonzaga, also spelled Lodovico (June 5, 1412 – June 12, 1478) was the ruler of the Italian city of Mantua from 1444 to his death in 1478. Ludovico was the son of Gianfrancesco Gonzaga and Paola Malatesta. He married Barbara of Brandenburg, niece of Emperor Sigismund, in 1437. He succeeded to the marquisate of Mantua in 1444.

Ludovico followed the path of his father Gianfrancesco, fighting as condottiero for the Visconti of Milan from 1446, but spent the following year in the service of Venice in the league formed with Florence against Milan. In 1450 he received permission to lead an army for King Alfonso of Naples in Lombardy, with the intent of gaining some possessions for himself. However, Francesco Sforza, the new duke of Milan, enticed him with the promise of Lonato, Peschiera and Asola, formerly Mantuan territories but then part of Venice. Venice responded by sacking Castiglione delle Stiviere (1452) and hiring Ludovico's brother, Carlo.

On June 14, 1453, Ludovico routed the troops of Carlo at Goito, but Venetian troops under Niccolò Piccinino thwarted any attempt to regain Asola. The Peace of Lodi (1454) obliged Ludovico to give back all his conquests, and to renounce definitively his claim to the three cities. However, he obtained his brother's land after Carlo's childless death in 1478.

The moment of highest prestige for Mantua was the Council held in the city from May 27, 1459 to January 19, 1460, summoned by Pope Pius II to launch a crusade against the Ottoman Turks, who had conquered Constantinople some years earlier.

In 1460, Ludovico appointed Andrea Mantegna as court artist to the Gonzaga family.

From 1466 he was more or less constantly at the service of the Sforza of Milan. He died in Goito in 1478, during a plague. He was buried in Mantua cathedral.

[3] Two Milanese ambassadors visiting the Camera Picta in 1470

In 1470 the Duke of Milan, Galeazzo Maria Sforza, sent two ambassadors to Mantua to discuss a renewal of the contract under which Marchese Ludovico Gonzaga had served for twenty years as lieutenant general of Milan. In their first report home, the Milanese envoys recount how they were received by Ludovico and how they were showed the Camera Picta, which was still unfinished at the time.

Afterwards [Lodovico] began talking about light matters and, after chatting for a while, showed us a room he is having painted where are portrayed al naturale his lordship, Madonna Barbara his consort, Lord Federico, and all his other sons and daughters. While talking about these figures, he had both his daughters come, namely the younger, Madonna Paola, and the elder, Madonna Barbara, who seemed to us a pretty and gentlev lady, with a good air and good manners.

Randolph Starn and Loren Patridge: Arts of Power: Three Halls of State in Italy, 1300-1600 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992), p. 84.

Mantegna devised an integrated scheme according to which the room is conceived as a pavilion, open on the sides and topped by an elaborate architectural framework perforated by a Classical oculus. As custom and practical considerations dictated, the ceiling must have been painted first. Inset within the classical intersecting ribs are roundels with simulated marble busts of the first eight Caesars. The roundels are surrounded by wreaths supported by putti strongly reminiscent of those painted by Castagno on the soffit of the arch of the chapel of S Tarasio in S Zaccaria, Venice. The oculus represents a tour de force of di sotto in sù illusionism. Winged putti, drastically foreshortened, play among the openings in the balustrade while women courtiers and domestics look into the room with a mixture of curiosity and amusement.

Over the fireplace on the north wall is the so-called Court Scene. Ludovico is shown surrounded by members of his family and to the right stand retainers wearing the Gonzaga colours. The Marchese is shown in conversation with his secretary, Marsilio Andreasi, while his dog Rubino rests comfortably under his chair. This image of the reigning marchese is that of an active paternalist governor, head of a secure dynasty. The figures stand before and behind the painted piers, which are crowned by real stone corbels from which the ceiling vaults spring. Mantegna subtly combined fictive elements with real ones, adapting viewpoints so that the spectator is constantly under pressure to believe the illusion and enter into the fiction of the represented scenes. Although it has been claimed that the Court Scene illustrates a specific historical moment (Signorini), it is more likely that it should be understood as an idealized group portrait of the ruler and his family. In 1470 the ambassadors of the Duke of Milan were taken to see the room and they witnessed that this wall was already completed.

On the west wall, adjacent to the Court Scene (which is painted largely in secco, hence its poorer state of preservation), is the Meeting Scene, representing an open-air encounter between Ludovico and his second son, Cardinal Francesco. Again it is unlikely that a specific moment is intended since among the other figures in the scene are the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick III, who never visited Mantua, and Christian I, King of Denmark and brother-in-law of Barbara of Brandenburg, who was in Mantua in 1474. A Classical city, exquisitely executed, dominates the landscape background behind the figures. In the lunettes are Gonzaga devices and above them are painted simulated reliefs set against painted gold mosaic backgrounds showing scenes from the stories of Arion, Hercules and Orpheus, which symbolically allude to Gonzaga virtues. Above the doorway in the west wall are putti bearing an inscribed stone slab in which Mantegna dedicated ‘this slight work’ (OPVS HOC TENVE) to Ludovico and Barbara. It is dated 1474. Despite the proclaimed modesty, Mantegna was doubtless counting on the viewer’s awareness that ‘tenue’ could also mean ‘subtle’ or ‘fine’ and a few centimetres away amidst the foliage decoration of the pilaster on the right he introduced his self-portrait.'

Source: The Grove Dictionary of Art

|

| This page uses material from the Wikipedia articles Andrea Mantegna and Ludovico II Gonzaga, Marquis of Mantua, published under the GNU Free Documentation License, and the The Grove Dictionary of Art. |

|

|