|

|

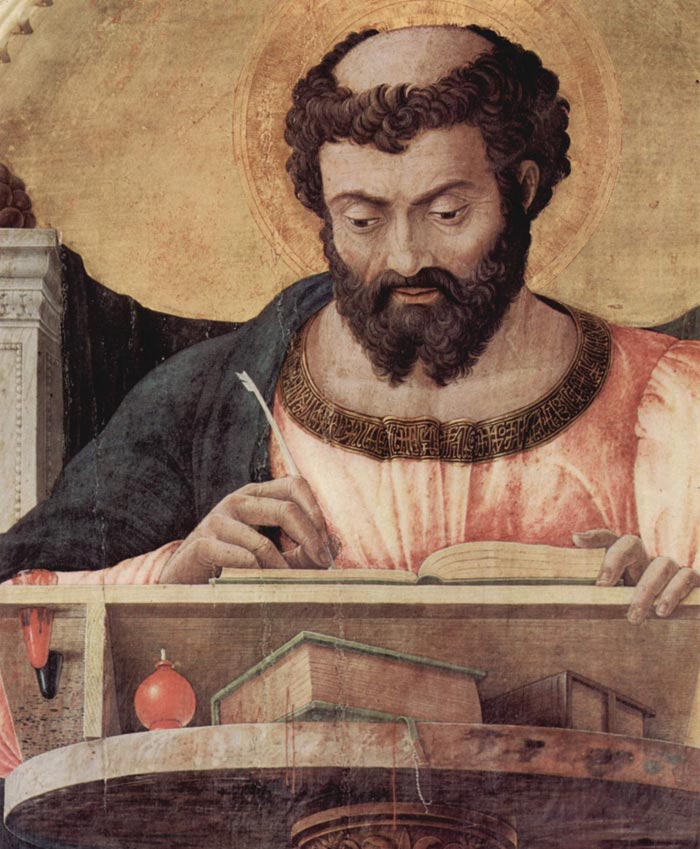

Andrea Mantegna, San Luca Altarpiece, (detail), 1453, panel, 177 x 230 cm, Milano, Pinacoteca di Brera |

|

Giorgio Vasari | Lives of the Most Eminent Painters Sculptors and Architects Andrea Mantegna |

| ANDREA MANTEGNA (1431-1506) PAINTER OF MANTUA |

||

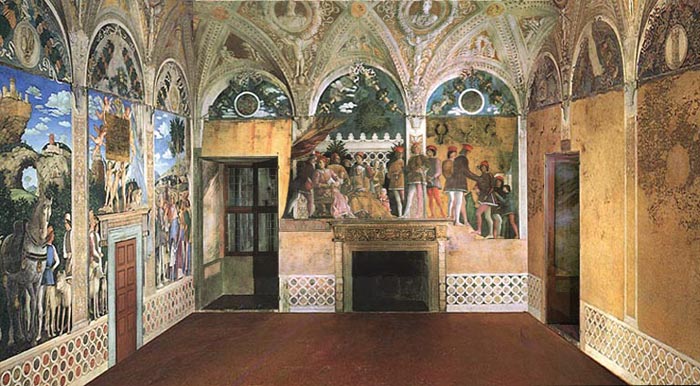

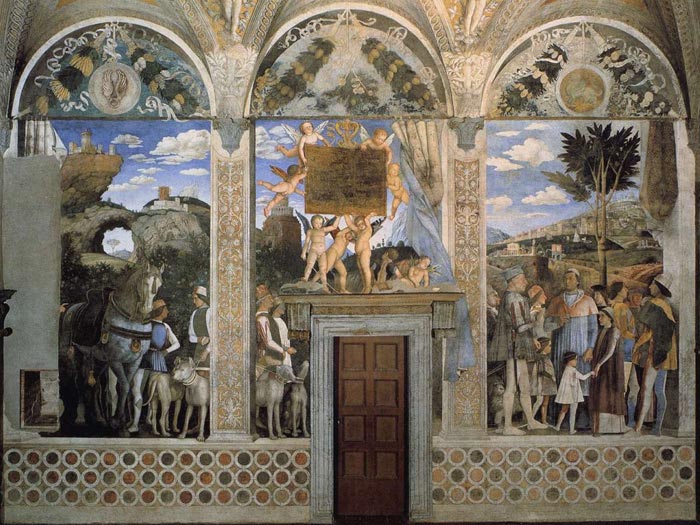

| How great is the effect of reward on talent is known to him who labors valiantly and receives a certain measure of recompense, for he feels neither discomfort, nor hardship, nor fatigue, when he expects honor and reward for them; nay, what is more, they render his talent every day more renowned and illustrious. It is true, indeed, that there is not always found one to recognize, esteem, and remunerate it as that of Andrea Mantegna was recognized. This man was born from very humble stock in the district of Mantua; and, although as a boy he was occupied in grazing herds, he was so greatly exalted by destiny and by his merit that he attained to the honorable rank of Chevalier, as will be told in the proper place. When almost full grown he was taken to the city, where he applied himself to painting under Jacopo Squarcione, a painter of Padua, who as it is written in a Latin letter from Messer Girolamo Campagnola to Messer Leonico Timeo, a Greek philosopher, wherein he gives him information about certain old painters who served the family of Carrara, Lords of Padua took him into his house, and a little time afterwards, having recognized the beauty of his intelligence, adopted him as his son. Now this Squarcione knew that he himself was not the most able painter in the world; wherefore, to the end that Andrea might learn more than he himself knew, he made him practise much on casts taken from ancient statues and on pictures painted upon canvas which he caused to be brought from diverse places, particularly from Tuscany and from Rome. By these and other methods, therefore, Andrea learnt not a little in his youth; and the competition of Marco Zoppo of Bologna, Dario da Treviso, and Niccolo Pizzolo of Padua, disciples of his master and adoptive father, was of no small assistance to him, and a stimulus to his studies. Now after Andrea, who was then no more than seventeen years of age, had painted the panel of the high altar of S. Sofia in Padua, which appears wrought by a mature and well-practised master, and not by a youth, Squarcione was commissioned to paint the Chapel of S. Cristofano, which is in the Church of the Eremite Friars of S. Agostino in Padua; and he gave the work to the said Niccolo Pizzolo and to Andrea. Niccolo made therein a God the Father seated in Majesty between the Doctors of the Church, and these paintings were afterwards held to be in no way inferior to those that Andrea executed there. And in truth, if Niccolo, whose works were few, but all good, had taken as much delight in painting as he did in arms, he would have become excellent, and might perchance have lived much longer than he did; for he was ever under arms and had many enemies, and one day, when returning from work, he was attacked and slain by treachery. Niccolo left no other works that I know of, save another God the Father in the Chapel of Urbano Perfetto.* [* This seems to be a printer's or copyist's error for Prefetto.] Andrea, thus left alone in the said chapel, painted the four Evangelists, which were held very beautiful. By reason of this and other works Andrea began to be watched with great expectation, and with hopes that he would attain to that success to which he actually did attain; wherefore Jacopo Bellini, the Venetian painter, father of Gentile and Giovanni, and rival of Squarcione, contrived to get him to marry his daughter, the sister of Gentile. Hearing this, Squarcione fell into such disdain against Andrea that they were enemies ever afterwards; and in proportion as Squarcione had formerly been ever praising the works of Andrea, so from that day onward did he ever decry them in public. Above all did he censure without reserve the pictures that Andrea had made in the said Chapel of S. Cristofano, saying that they were worthless, because in making them he had imitated the ancient works in marble, from which it is not possible to learn painting perfectly, for the reason that stone is ever from its very essence hard, and never has that tender softness that is found in flesh and in things of nature, which are pliant and move in various ways; adding that Andrea would have made those figures much better, and that they would have been more perfect, if he had given them the colour of marble and not such a quantity of colors, because his pictures resembled not living figures but ancient statues of marble or other suchlike things. This censure piqued the mind of Andrea; but, on the other hand, it was of great service to him, for, recognizing that Squarcione was in great measure speaking the truth, he set himself to portray living people, and made so much progress in this art, that, in a scene which still remained to be painted in the said chapel, he showed that he could wrest the good from living and natural objects no less than from those wrought by art. But for all this Andrea was ever of the opinion that the good ancient statues were more perfect and had greater beauty in their various parts than is shown by nature, since, as he judged and seemed to see from those statues, the excellent masters of old had wrested from living people all the perfection of nature, which rarely assembles and unites all possible beauty into one single body, so that it is necessary to take one part from one body and another part from another. In addition to this, it appeared to him that the statues were more complete and more thorough in the muscles, veins, nerves, and other particulars, which nature, covering their sharpness somewhat with the tenderness and softness of flesh, sometimes makes less evident, save perchance in the body of an old man or in one greatly emaciated; but such bodies, for other reasons, are avoided by craftsmen. And that he was greatly enamored of this opinion is recognized from his works, in which, in truth, the manner is seen to be somewhat hard and sometimes suggesting stone rather than living flesh. Be this as it may, in this last scene, which gave infinite satisfaction, Andrea portrayed Squarcione in an ugly and corpulent figure, lance and sword in hand. In the same work he portrayed the Florentine Noferi, son of Messer Palla Strozzi, Messer Girolamo della Valle, a most excellent physician, Messer Bonifazio Fuzimeliga, Doctor of Laws, Niccolo', goldsmith to Pope Innocent VIII, and Baldassarre da Leccio, all very much his friends, whom he represented clad in white armor, burnished and resplendent, as real armor is, and truly with a beautiful manner. He also portrayed there the Chevalier Messer Bonramino, and a certain Bishop of Hungary, a man wholly witless, who would wander about Rome all day, and then at night would lie down to sleep like a beast in a stable; and he made a portrait of Marsilio Pazzo in the person of the executioner who is cutting off the head of S. James, together with one of himself. This work, in short, by reason of its excellence, brought him a very great name. The while that he was working on this chapel, he also painted a panel, which was placed on the altar of S. Luca in S. Giustina, and afterwards he wrought in fresco the arch that is over the door of S. Antonino, on which he wrote his name. In Verona he painted a panel for the altar of S. Cristofano and S. Antonio, and he made some figures at the corner of the Piazza, della Paglia. In S. Maria in Organo, for the Monks of Monte Oliveto, he painted the panel of the high altar, which is most beautiful, and likewise that of S. Zeno. And among other things that he wrought while living in Verona and sent to various places, one, which came into the hands of an Abbot of the Abbey of Fiesole, his friend and relative, was a picture containing a half-length Madonna with the Child in her arms, and certain heads of angels singing, wrought with admirable grace; which picture, now to be seen in the library of that place, has been held from that time to our own to be a rare thing. Now, the while that he lived in Mantua, he had labored much in the service of the Marquis Lodovico Gonzaga, and that lord, who always showed no little esteem and favor towards the talent of Andrea, caused him to paint a little panel for the Chapel of the Castle of Mantua; in which panel there are scenes with figures not very large but most beautiful. In the same place are many figures foreshortened from below upwards, which are greatly extolled, for although his treatment of the draperies was somewhat hard and precise, and his manner rather dry, yet everything there is seen to have been wrought with much art and diligence. For the same Marquis, in a hall of the Palace of S. Sebastiano in Mantua, he painted the Triumph of Caesar, which is the best thing that he ever executed. In this work we see, grouped with most beautiful design in the triumph, the ornate and lovely car, the man who is vituperating the triumphant Caesar, and the relatives, the perfumes, the incense, the sacrifices, the priests, the bulls crowned for the sacrifice, the prisoners, the booty won by the soldiers, the ranks of the squadrons, the elephants, the spoils, the victories, the cities and fortresses counterfeited in various cars, with an infinity of trophies borne on spears, and a variety of helmets and body armor, headdresses, and ornaments and vases innumerable; and in the multitude of spectators is a woman holding the hand of a boy, who, having pierced his foot with a thorn, is showing it, weeping, to his mother, in a graceful and very lifelike manner. Andrea, as I may have pointed out elsewhere, had a good and beautiful idea in this scene, for, having set the plane on which the figures stood higher than the level of the eye, he placed the feet of the foremost on the outer edge and outline of that plane, making the others recede inwards little by little, so that their feet and legs were lost to sight in the proportion required by the point of view; and so, too, with the spoils, vases, and other instruments and ornaments, of which he showed only the lower part, concealing the upper, as was required by the rules of perspective; which same consideration was also observed with much diligence by Andrea degli Impiccati* [* Andrea dal Castagno.] in the Last Supper, which is in the Refectory of S. Maria Nuova. Wherefore it is seen that in that age these able masters set about investigating with much subtlety, and imitating with great labor, the true properties of natural objects. And this whole work, to put it briefly, is as beautiful and as well wrought as it could be; so that if the Marquis loved Andrea before, he loved and honored him much more ever afterwards. What is more, he became so famous thereby that Pope Innocent VIII, hearing of his excellence in painting and of the other good qualities wherewith he was so marvellously endowed, sent for him, even as he was sending for many others, to the end that he might adorn with his pictures the walls of the Belvedere, the building of which had just been finished. Having gone to Rome, then, greatly favored and recommended by the Marquis, who made him a Chevalier in order to honor him the more, he was received lovingly by that Pontiff and straightway commissioned to paint a little chapel that is in the said place. This he executed with diligence and love, and with such minuteness that the vaulting and the walls appear rather illuminated than painted ; and the largest figures that are therein, which he painted in fresco like the others, are over the altar, representing the Baptism of Christ by S. John, with many people around, who are showing by taking off their clothes that they wish to be baptized. Among these is one who, seeking to draw off a stocking that has stuck to his leg through sweat, has crossed that leg over the other and is drawing the stocking off inside out, with such great effort and difficulty, that both are seen clearly in his face; which bizarre fancy caused marvel to all who saw it in those times. It is said that this Pope, by reason of his many affairs, did not pay Mantegna as often as he would have liked, and that therefore, while painting certain Virtues in terretta in that work, he made a figure of Discretion among the rest, whereupon the Pope, having gone one day to see the work, asked Andrea what figure that was; to which Andrea answered that it was Discretion; and the Pope added: "If thou wouldst have her suitably accompanied, put Patience beside her." The painter understood what the meaning of the Holy Father was, and he never said another word. The work finished, the Pope sent him back to the Duke with much favor and honorable rewards. The while that Andrea was working in Rome, he painted, besides the said chapel, a little picture of the Madonna with the Child sleeping in her arms; and within certain caverns in the landscape, which is a mountain, he made some stone-cutters quarrying stone for various purposes, all wrought with such delicacy and such great patience, that it does not seem possible for such good work to be done with the thin point of a brush. This picture is now in the possession of the most Illustrious Lord, Don Francesco Medici, Prince of Florence, who holds it among his dearest treasures. In our book is a drawing by the hand of Andrea on a half-sheet of royal folio, finished in chiaroscuro, wherein is a Judith who is putting the head of Holofernes into the wallet of her Moorish slave-girl; which chiaroscuro is executed in a manner no longer used, for he left the paper white to serve for the light in place of white lead, and that so delicately that the separate hairs and other minute details are seen therein, no less than if they had been wrought with much diligence by the brush; wherefore in a certain sense this may be called rather a work in color than a drawing. The same man, like Pollaiuolo, delighted in engraving on copper; and, among other things, he made engravings of his own Triumphs, which were then held in great account, since nothing better had been seen One of the last works that he executed was a panel picture for S. Maria della Vittoria, a church built after the direction and design of Andrea by the Marquis Francesco, in memory of the victory that he gained on the River Taro, when he was General of the Venetian forces against the French. In this panel, which was wrought in distemper and placed on the high altar, there is painted the Madonna with the Child seated on a pedestal; and below are S. Michelagnolo, S. Anna, and Joachim, who are presenting the Marquis who is portrayed from life so well that he appears alive to the Madonna, who is offering him her hand. Which picture, even as it gave and still continues to give universal pleasure, also satisfied the Marquis so well that he rewarded most liberally the talent and labor of Andrea, who, having been remunerated by Princes for all his works, was able to maintain his rank of Chevalier most honorably up to the end of his life. Andrea had competitors in Lorenzo da Lendinara who was held in Padua to be an excellent painter, and who also wrought some things in terracotta for the Church of S. Antonio and in certain others of no great worth. He was ever the friend of Dario da Treviso and Marco Zoppo of Bologna, since he had been brought up with them under the discipline of Squarcione. For the Friars Minor of Padua this Marco painted a loggia which serves as their chapterhouse; and at Pesaro he painted a panel that is now in the new Church of S. Giovanni Evangelista; besides portraying in a picture Guidobaldo da Montefeltro, at the time when he was Captain of the Florentines. A friend of Mantegna's, likewise, was Stefano, a painter of Ferrara, whose works were few but passing good; and by his hand is the adornment of the sarcophagus of S. Anthony to be seen in Padua, with the Virgin Mary, that is called the Vergine del Pilastro. But to return to Andrea himself; he built a very beautiful house in Mantua for his own use, which he adorned with paintings and enjoyed while he lived. Finally he died in 1517, at the age of sixty-six, and was buried with honorable obsequies in S. Andrea; and on his tomb, over which stands his portrait in bronze, there was placed the following epitaph: ESSE PAREM HUNG NORIS, SI NON PRjEPONIS, APELIT, jENEA MANTINÉE QUI SIMULACRA VIDES. Andrea was so kindly and praiseworthy in all his actions, that his memory will ever live, not only in his own country, but in the whole world; wherefore he well deserved, no less for the sweetness of his ways than for his excellence in painting, to be celebrated by Ariosto at the beginning of his thirty-third canto, where he numbers him among the most illustrious painters of his time, saying: Leonardo, Andrea Mantegna, Gian Bellino. This master showed painters a much better method of foreshortening figures from below upwards, which was truly a difficult and ingenious invention; and he also took delight, as has been said, in engraving figures on copper for printing, a method of truly rare value, by means of which the world has been able to see not only the Bacchanalia, the Battle of Marine Monsters, the Deposition from the Cross, the Burial of Christ, and His Resurrection, with Longinus and S. Andrew, works by Mantegna himself, but also the manners of all the craftsmen who have ever lived. |

|

[1] Vasari, Giorgio (b Arezzo, 30 July 1511; d Florence, 27 June 1574). Italian painter, architect, and writer, active mainly in Florence and Rome. In his day he was a leading painter, architect, and artistic impresario, but his activities in these fields have been completely overshadowed by his role as the most important of all artistic biographers. His great book, generally referred to as Lives of the Artists, has earned him the title of the father of art history; it is not only the fundamental source of information on Italian Renaissance art, but also a key document in shaping attitudes about the period for centuries afterwards. (The book was first published in Florence in 1550 as Le vite de' più eccellenti architetti, pittori, et scultori italiani—The Lives of the Most Eminent Italian Architects, Painters, and Sculptors; in 1568 there was a second, much enlarged edition, in which the title is slightly changed, the painters being mentioned first. In addition to biographies, the book contains a lengthy introduction dealing with artists' materials and techniques.) Vasari wrote from a particular aesthetic viewpoint, and his book is not only a collection of biographical information but also a critical history of style. He believed that art is in the first instance imitation of nature and that progress in painting consists in the perfecting of the means of representation. He thought that such representational skills had been taken to high levels in classical antiquity, that art had then passed through a long period of decline in the Middle Ages, and that it had begun to revive in the 14th century in Tuscany (he was heavily biased in favour of his own region). The main theme of the Lives was to set forth this revival—its initiation by Cimabue and Giotto, its steady advance at the hands of such artists as Brunelleschi, Donatello, and Masaccio, and its culmination with Leonardo, Raphael, and above all Michelangelo, whom Vasari idolized and whose biography was the only one of a living artist to appear in the first edition of his book (the second edition adds accounts of several artists then living, including Vasari's autobiography). The idea of artistic ‘progress’ that he promoted subsequently coloured most writing on the period. Given the wide scope and vast size of the book (the second edition has roughly the same wordage as the Bible), it is not surprising that it contains many errors and contentious points (see, for example, Andrea del Castagno and Andrea del Sarto). However, by the standards of the time Vasari was a diligent researcher and he gathered together an enormous amount of invaluable information, which he presented in a lively style, full of memorable anecdotes. Moreover, his qualitative judgements have generally stood the test of time well: the artists and works he most admired are by and large still the ones we most admire today. His book became the model for artistic biographers in other countries, such as van Mander in the Netherlands, Sandrart in Germany, and Palomino in Spain. As a painter, Vasari was one of the most prolific decorators of his period, but he is not now highly regarded, his work representing the most in-bred and affected kind of Mannerism. His best-known achievement in this field is probably the decoration (1546) of the grand salon in the Palazzo della Cancelleria, Rome, with scenes celebrating the life of Pope Paul III, commissioned by his grandson Cardinal Alessandro Farnese. Pressed for quick results by the cardinal, Vasari enlisted a team of assistants and finished the work within 100 days, earning the room its nickname of the Sala dei Cento Giorni. When Michelangelo was told of the remarkable speed with which the work had been accomplished, he is said to have made the withering response ‘E si vede’ (So it appears). As an architect Vasari has a higher reputation; his most important building is the Uffizi in Florence, and he designed and decorated his own house in Arezzo, now a museum dedicated to him. Vasari was the first important collector of drawings, using them partly as research material for his biographies, for the insight they gave into the creative process, and he also played the leading role in establishing Florence's Accademia del Disegno. [IAN CHILVERS. "Vasari, Giorgio." The Oxford Dictionary of Art. 2004. Encyclopedia.com. (June 13, 2011).] |

||||

Art in Tuscany | Art in Tuscany | Giorgio Vasari | Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects |

||||

|

Art in Tuscany | Andrea Mantegna |

||||

Holiday accomodation in Tuscany | Podere Santa Pia | Artist and writer's residency

|

||||

Podere Santa Pia |

Podere Santa Pia, garden view, April |

View from Podere Santa Pia

on the coast and Corsica |

||

Podere Santa Pia, garden view, December |

Piazza della Santissima Annunziata in Florence |

Perugia |

||

The façade and the bell tower of San Marco in Florence |

Piazza della Santissima Annunziata in Florence |

Florence, Duomo |

||