|

|

| I T | Benozzo Gozzoli, The Magi Chapel in Palazzo Medici Riccardi of Florence |

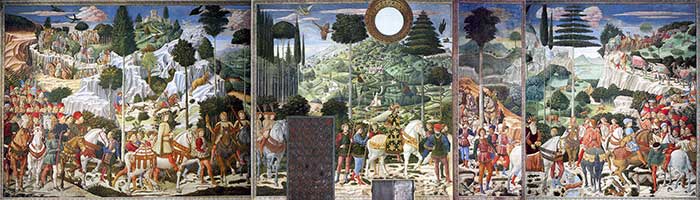

Benozzo Gozzoli | Procession of the Magi in the Palazzo Medici-Riccardi in Florence (1459-60) |

Benozzo Gozzoli (c. 1421 – 1497) was an Italian Renaissance painter from Florence. Gozzoli was trained by both Lorenzo Ghiberti and Fra Angelico and from them he evolved a narrative style of great charm. He is best known for a series of murals in the Palazzo Medici-Riccardi depicting festive, vibrant processions with wonderful attention to detail and a pronounced International Gothic influence. The Chapel of the Magi, built and decorated in the fifteenth century, features a harmonious decoration of enchanting beauty. The frescoes of Benozzo Gozzoli, more famous even than the artist himself, constitute one of the most eminent illustrations of Medici Florence. |

||

|

||

| As early as 1442 Pope Martin V had given the Medicis permission to build a private chapel with a portable family altar. The chapel, in the first floor of the Medicis' private residence, was built by Michelozzo di Bartolomeo between 1446 and 1449 and dedicated to the Holy Trinity. It comprises an almost square main room and, one step higher, an equally nearly square chancel. The two are separated from each other by two Corinthian pillars.[1] |

||

In the apse the ranks of angels, with marvelously ornate clothes and wings, are depicted in the act of flying, singing, worshipping on their knees, and weaving festoons of flowers; the verses inscribed in their haloes tell us that the hymn they are intoning is the Gloria.

|

|

|

|

||

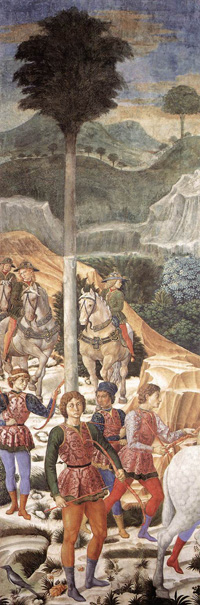

Benozzo Gozzoli, Procession of the Youngest King (detail), 1459-60, Palazzo Medici-Riccardi, Firenze |

||

|

||

| Benozzo Gozzoli, Procession of the Youngest King (detail), 1459-60, Palazzo Medici-Riccardi, Firenze |

||

Procession of the Youngest King (east wall) |

||

|

||

Benozzo Gozzoli, Procession of the Youngest King (detail), 1459-60, Palazzo Medici-Riccardi, Firenze |

||

| Over a rich landscape probably influenced by Flemish artists (perhaps through tapestries), Gozzoli portrayed the members of the Medici family riding in the foreground of the fresco on the wall at the right of the altar. A young Lorenzo il Magnifico leads the procession on a white horse, followed by his father Piero the Gouty and the family founder, Cosimo. Then come Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta and Galeazzo Maria Sforza, respectively lord of Rimini and Milan: they did not take part in the Council, but were guests of the Medici in Florence in the time the frescoes were painted. After them is a procession of illustrious Florentines, such as the humanists Marsilio Ficino and the Pulci brothers, the members of the Art Guilds and Benozzo himself. The painter can be recognized for he is looking towards the observer and for the scroll on his red hat, reading Opus Benotii. | ||

With a landscape background filling the rest of of the pictorial space, this fresco was designed like contemporary tapestries, a new type of courtly art destined for wealthy patrons. |

|

|

| Benozzo has also immortalized himself in the densely crowded retinue in close proximity to the "familiari". We know this from the inscription of his name on the red cap. In recent research the two youths in front of Benozzo have been identified as Lorenzo and Giuliano Medici. By having themselves depicted in the procession of the Three Kings, the Medicis were demonstrating both their political and their financial power. They had themselves depicted at the end of the procession, as part of the youngest king's retinue, and not as part of the retinue of the oldest king, who is nearest their goal. |

|

|

| Members of the Medici family are portrayed in the youngest king's retinue. For example, the man riding on a brown mule has been identified as Cosimo de' Medici (1389-1464). Benozzo Gozzoli placed his own self-portrait among the Medicis. His red cap bears the inscription BENOTII. He is standing behind two youths, who, it is now believed, portray Lorenzo and Giuliano de' Medici. |

||

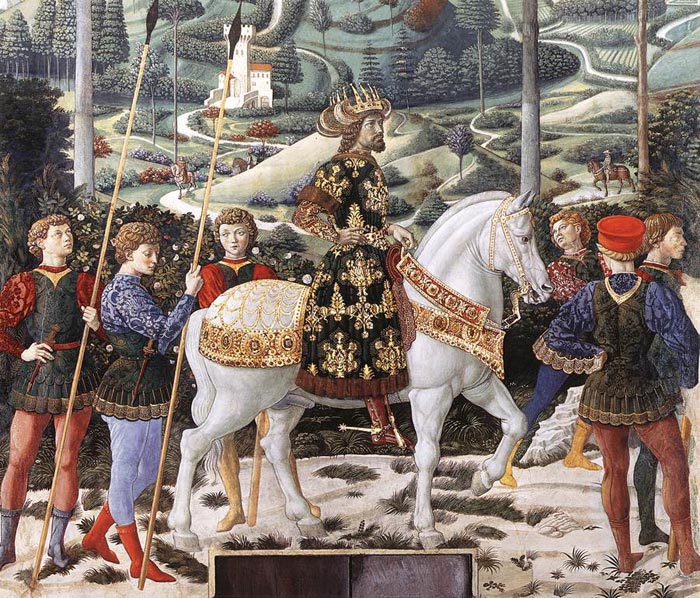

| So magnificent a procession with so many figures, which in addition was in a family chapel and not in a public church, was ideally suited for incorporating portraits of famous contemporaries. However, the identification of the youngest king as Lorenzo de' Medici, which can be first proven to have appeared in a travel guide in the late 19th century, is purely a figment of the imagination. Despite the seven spheres of the Medici coat of arms in the oval golden medals on his horse's bridle, such an identification is impossible due to the age of the depicted man - at the time the work was painted, Lorenzo was not yet ten years old. |

East Wall, alleged portrait of Lorenzo il Magnifico.

The youngest of the Magi was thought to be a likeness of Lorenzo the Magnificent. He is at the head of a cortege which includes Cosimo de' Medici, Piero the Lame and his brother Giuliano. Lorenzo's face is characterized by shining eyes, a strong, square jaw and fine mouth. However, it is not probable since at the time the work was created, he was just ten years old. |

|

Most of the figures in the Procession of the Magi were painted from live models and given the likeness of Benozzo Gozzoli's contemporaries. The painter tried to represent as many likeness as possible, often without concern for the actual space taken up by the body. Only a few figures enjoy sufficient space. The artist's self-portrait is indicated by an inscription BENOTII on his hat.[2] |

||

Procession of the Middle King (south wall) |

||

|

||

Benozzo Gozzoli, Procession of the Middle King (south wall), 1459-60, fresco, Chapel, Palazzo Medici-Riccardi, Florence |

||

On the following wall, the bearded character on a white horse is the Byzantine emperor John VIII Palaiologos. The three girls next to him have been identified as the three daughters of Piero de' Medici, Nannina, Bianca and Maria. |

||

| The middle king is represented with the features of Emperor John VII Paleologus. For this representation Benozzo based his work on a medallion designed by Pisanello in 1438. However, he made the face younger and replace the traditional and unwieldy Byzantine tiara with a crown resting on a peacock-plumed velvet cap.[3] | ||

Procession of the Old King (west wall) |

||

|

||

Benozzo Gozzoli, Procession of the Old King (west wall), 1459-60, fresco, Chapel, Palazzo Medici-Riccardi, Florence |

||

The oldest king is closest to the Christ Child on the altarpiece and is followed by the largest procession of pilgrims. His vanguard is made to appear visually longer due to the about-turn that the procession makes. He is wisely and calmly gazing towards the young king on the opposite wall. His long gray full beard shows him to be from the Middle East, for the Florentines of the 15th century, where a smoothly shaved face was the predominant fashion, considered this to be the decisive characteristic of the Orient.

|

||

|

||

Benozzo Gozzoli, Procession of the Old King (detail, west wall), 1459-60, fresco, Chapel, Palazzo Medici-Riccardi, Florence

|

||

| The young herald riding before the old king corresponds formally with the figure of the young king on the opposite wall. On the right side of the image a group of supporters or agents of the Medici can be seen, such as Bernardo Giugni, Francesco Sassetti, Agnolo Tani, and perhaps Dietisalvi Neroni and Luca Pitti, who were to become enemies in 1466. |

||

| In 1659, the Riccardi family bought the Palazzo Medici and undertook some structural changes. This included, in 1689, the building of an exterior flight of stairs leading up to the first floor. For this purpose the entrance to the chapel had to be moved. During the process, two sections of wall were cut out of the south western corner, in the Procession of the Oldest King. After the stairs were finished, the cut out elements were mounted on a corner of the wall projecting into the room. During the course of this, the oldest king's horse was cut up and mounted on two different segments of the wall. The picture shows the backfill wall with the cut out section of the procession of the old king. | ||

[1] Built in the mid fifteenth century by Michelozzo on commission from the Medici, the Palazzo Medici became the prototype of Renaissance civil architecture. The robust and austere pile of the mansion, originally designed as a sort of cube, was for at least a century the most direct and efficacious symbol of the political and cultural primacy of the Medici in Florence. Representation in art

|

In 1659, the Riccardi family bought the Palazzo Medici and undertook some structural changes. This included, in 1689, the building of an exterior flight of stairs leading up to the first floor. For this purpose the entrance to the chapel had to be moved. During the process, two sections of wall were cut out of the south western corner, in the Procession of the Oldest King. After the stairs were finished, the cut out elements were mounted on a corner of the wall projecting into the room. During the course of this, the oldest king's horse was cut up and mounted on two different segments of the wall. The picture shows the backfill wall with the cut out section of the procession of the old king. |

|

|

|

||

This page is published under the GNU Free Documentation License. It uses material from the Wikipedia articles Magi Chapel and Palazzo Medici Riccardi. |

||

Holiday accomodation in Tuscany | Podere Santa Pia | Artist and writer's residency

|

||||

Podere Santa Pia |

Podere Santa Pia, garden view, April |

View from terrace with a stunning view over the Maremma and Montecristo |

||

Abbadia d’Ombrone and Monastero d’Ombrone near Castelnuovo Berardenga. |

Arcidosso |

Montalcino | ||

Palazzo Medici Riccardi, Florence |

Piazza della Santissima Annunziata in Florence |

Florence, Duomo |

||

|

|

|

||

San Gimignano |

Abbazia di Monte Oliveto Maggiore |

San Marco, Firenze |

||