| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| I T

|

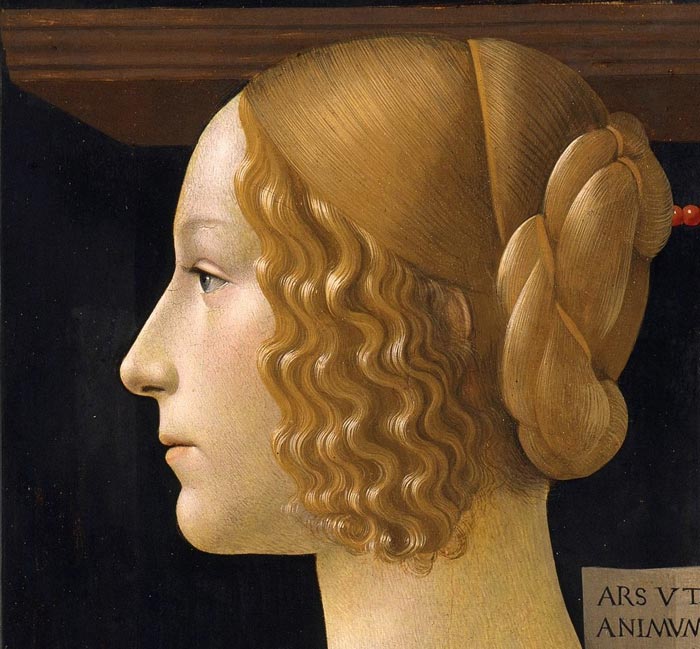

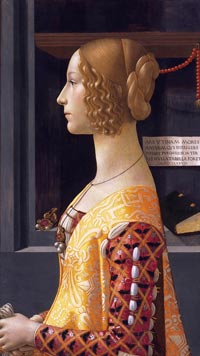

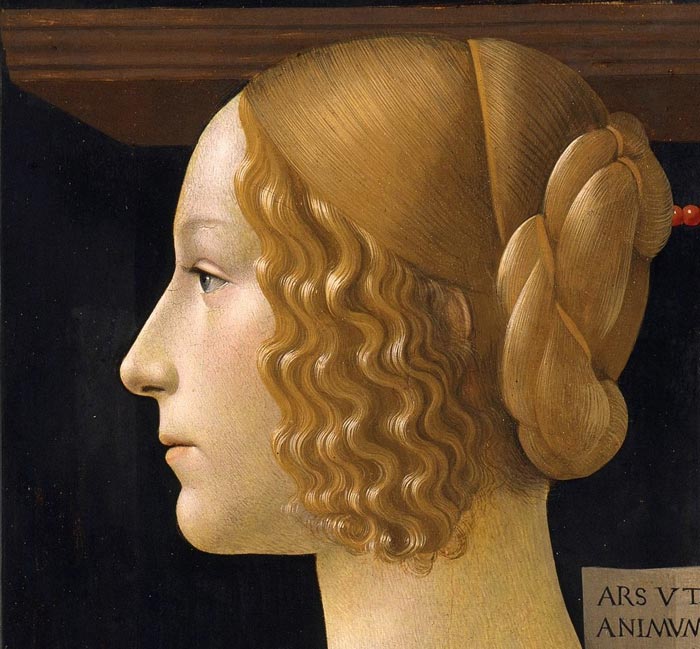

Domenico Ghirlandaio, Giovanna degli Albizzi Tornabuoni (detail), c. 1488/1490, tempera on panel, Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

Domenico Ghirlandaio | Portrait of Giovanna degli Albizzi Tornabuoni

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Independent portraits of women were rare prior to the mid-15th century. They often depicted a prospective partner for a royal or noble marriage. More common for the time were ruler portraits depicting both husband and wife. These portraits were likely executed in the traditional profile view because of its association with ancient coins and medallions.

As the 15th century progressed, portraits of females, independent of men, increased in popularity. The story that lies behind Ghirlandaio’s painted image of Giovanna degli Albizzi Tornabuoni is as captivating as the work of art itself. More than 500 years after it was painted, the panel now opens a window onto Florentine, Early Renaissance culture: a journey in time that will reveal to us the nature of life in this flourishing 15th-century city, its social and commercial relations and its religious convictions and domestic life.

Domenico Ghirlandaio incorporated portraits of his contemporaries in many biblical scenes. It is probably for precisely that reason that he was so popular among the rich Florentines, who were particularly keen on self portrayal. This makes it all the more astonishing that so few secular portraits by Ghirlandaio have survived.

There are two paintings dating from about 1490, in the Paris Musée du Louvre and in Madrid, that are masterpieces of his art and yet fundamentally different: Giovanna Tornabuoni is idealized to the extent of becoming an "icon" of beauty for young Florentine girls, while the old man with the boy is painted with a pitiless degree of realism. Ghirlandaio does not shrink even from depicting his nose in all its disfigurement.

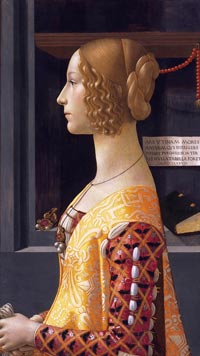

The painting in Madrid depicts Giovanna degli Albizzi in a magnificent garment made of gold brocade with tight, slitted silk sleeves. She came from one of the most important Florentine families and in 1486 married Lorenzo Tornabuoni. After her early death Ghirlandaio created two portraits, and it is possible that he was able to produce the cartoon for them while she was still alive.

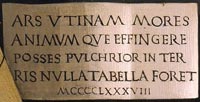

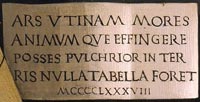

She is wearing a valuable piece of jewelry, comprising a ruby in a gold setting with three silky shining pearls, hanging from her neck by a delicate cord. There is a very similar item of jewelry on the shelf behind her, and this, combined with red coral beads against the black background, gives the work a noble elegance. These beads are part of a rosary, and the section that is hanging straight down emphasizes the vertical line of her back, and also directs our gaze to the prayer book. Between these two "pious" objects is a little note alluding to the beautiful soul of the portrayed woman by means of an epigram written by the Roman poet Martial in the first century A.D.: Ars utinam mores animumque effigere posses pulchrior in terris nulla tabella foret. (Art, if only you could portray mores and spirit, there would be no more beautiful picture on earth).

|

The young Giovanna, born in 1468 into one of the city’s leading families, married Lorenzo, a high-born youth from another prominent family – the Tornabuoni, who were related to the Medici- in 1486. The panel reveals how his life was blighted by the death of his young wife while she was pregnant with their second child and how the grief-stricken young man turned to one of the great masters of the day and a friend of the family, Domenico Ghirlandaio, to commission a portrait that would allow him to commemorate and honour the memory of his wife for posterity through an image that would reflect her interior as well as her exterior beauty:

A R S V T I N A M M O R E S

A N I M V M Q V E E F F I N G E R E

P O S S E S P V L C H R I O R I N T E R R I S N V L L A T A B E L L A F O R E T

M C C C C L X X X V I I I: “If only art could reproduce the character and spirit! In all the world a more beautiful painting will not be found.”

The profile view commonly used for early Renaissance painted portraits conforms to the format of portrait medals, which Pisanello introduced in the 1430s. His Cecilia Gonzaga, representing the daughter of the duke of Mantua, is the first known Renaissance medal to portray a woman. Reflecting the humanist fascination with the classical past, medals emulated ancient Roman coins depicting the Caesars in strict profile. As the profile view was also used for images of female saints, it was eminently suitable for portraits of young brides, who were expected to bring honor to their husbands' families through virtuous behavior. The upright posture and averted gaze dictated by the profile format reinforced the impression of moral rectitude and echoed the Renaissance theorist Leon Battista Alberti's admonition that young women should comport themselves with self-restraint and "a grave demeanor." The painted profile portrait generally went out of vogue in the late fifteenth century, although it was still used under special circumstances. Domenico Ghirlandaio's Giovanna degli Albizzi Tornabuoni, for example, is a posthumous portrait, apparently commissioned by Giovanna's husband to preserve the memory of his young wife, who had died in childbirth.

|

|

Domenico Ghirlandaio, Giovanna degli Albizzi Tornabuoni, c. 1488/1490, tempera on panel, Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

|

“If only art could reproduce the character and spirit! In all the world a more beautiful painting will not be found.”

This is the inscription to be found on the cartouche that Ghirlandaio included in the portrait. The words are a variant of the end of an epigram by the poet Martial. The text has a double meaning, firstly referring to the virtues possessed by Giovanna during her lifetime and which could barely be reproduced in images, and secondly, exalting the art of painting and expressing a concept on the lines of “see what painting is capable of”. There is also no doubt that the commission from the Tornabuoni, to whom the artist was closely linked, encouraged Ghirlandaio to exert all his efforts and produce the best of which he was capable. The panel is still in magnificent condition, allowing us to appreciate the great care with which it was painted. The face, hands, clothing and objects surrounding Giovanna are painted with great beauty and delicacy. The panel occupied a place of honour in one of Lorenzo Tornabuoni’s apartments in the family palace, which was among the most sumptuous in Florence along with those of the Medici. It was displayed in a wide, gilded frame in the “chamera del palco d’oro”, a room that had a gilded ceiling and other gilded elements and was located close to the “chamera di Lorenzo, bella”, which was the young man’s private chamber.

Important paintings were made for the decoration and furnishings of Lorenzo’s chamber in Palazzo Tornabuoni, the symbolic centre of his own, new household.

Works that graced Lorenzo’s luxurious chamera include three beautifully preserved panels illustrating the story of Jason and Medea and the spectacular tondo by Domenico Ghirlandaio with the Adoration of the Magi. Together with scenes from the Trojan War, these pictures exalted the Greco-Roman concept of heroism as well as lofty Christian ideals, against the background of great cultural optimism and the belief in a new Golden Age.

|

|

A R S V T I N A M M O R E S

A N I M V M Q V E E F F I N G E R E

P O S S E S P V L C H R I O R I N T E R

R I S N V L L A T A B E L L A F O R E T

M C C C C L X X X V I I I |

In a fresco in the Tornabuoni Chapel, Giovanna is depicted as an entire figure witnessing the Visitation. The artist used that portrait in his panel painting with a new background, though he unfortunately cut the arms and hands off rather awkwardly. The delightful young woman now stands out, in a clear contrast of light against dark, from the black niche in the background. The reserved beauty of the young woman is fittingly expressed in the formal clarity of the composition.

Giovanna degli Albizzi had married Lorenzo Tornabuoni in 1486 when she was not yet eighteen years old -- a marriage arranged through the mediation of Lorenzo's cousin, Lorenzo the Magnificent.

The marriage had been a sumptuous occasion, marking the union of two among the most important and oldest Florentine families which in the first half of the century had been political enemies. A cortège of one hundred well-born girls and fifteen young men had accompanied Giovanna to the cathedral of Florence, Santa Maria del Fiore, where the wedding ring was given to her in presence of the Spanish ambassador to the Pope. The festivities included banquets and dances organised on wooden platforms, specially built for the occasion next to the Tornabuoni and the Albizzi palaces. In October 1487, Giovanna had given birth to Giovanni Tornabuoni's first grandson, who had been also called Giovanni. By the time Ghirlandaio painted her portrait in the Visitation, she was already dead. She died one year after the birth of her son, during a new pregnancy, and was buried in S. Maria Novella.

Giovanni's posthumous portrait in this cycle confirms to posterity the importance of her place amongst the Tornabuoni, as she was the means through which the family name was transmitted to a new generation. The hieratic character of her image is stressed, through the repetition of pose and garments, by another portrait painted in the story facing the Visitation fresco.

The fine background shows the influence of both classical and Flemish art on Ghirlandaio. On the right is an ancient edifice, while the city landscape on the right is typical of Early Netherlandish painting. The balcony in the middle with two young men stretching out is probably a reference to Jan van Eyck's Madonna of Chancellor Rolin, or to Rogier van der Weyden's St. Luke Painting the Madonna. Two other figures are portrayed walking upwards next to the dividing wall. The city is fanciful, but details like the tower of Florence's Palazzo Vecchio and the Santa Maria Novella campanile, as well as Rome's Colosseum are from real buildings.

All the elements in this picture were explicitly required in Tornabuoni's contract with Ghirlandaio: the landscape, the city, the animals, the perspective, the portraits and the classical elements.

Art in Tuscany | Domenico Ghirlandaio | The Tornabuoni Chapel

|

|

|

| Domenico Ghirlandaio had several prominent patrons, who he painted a number of portraits of; including the Medici family and the Tornabuoni family. His piece, Adoration of the Magi, from 1487 of the Giovanni Tornabuoni collection, has been at the Uffizi Gallery since 1790.

The marriage between Giovanna degli Albizzi and Lorenzo Tornabuoni is the best documented of all those that took place in late 15th-century Florence. So splendid was this event that it was still written about a century later, and there are numerous works of art directly related to it, including the frescoes commissioned from Botticelli for the family’s country residence. The most splendid acquisitions were undoubtedly those made to decorate and furnish Lorenzo’s chamber, the symbolic centre of the couple’s new home. The paintings for the “chamera di Lorenzo, bella” in the Palazzo Tornabuoni still survive, most of them in outstandingly good condition. Four of them will now be seen together for the first time in 500 years, including the magnificent tondo of The Adoration of the Magi, a masterpiece by Ghirlandaio and an exceptional loan from the Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence. The exhibition will provide a unique occasion on which to see these works displayed together and juxtaposed with other paintings and objects that illustrate the context of the wedding. The exhibition brings together a fascinating group of secular images of various types that reveal the cultural values described in the nuptial poem that the humanist Naldo Naldi wrote on the occasion of this event. The texts and works of art related to the wedding also open a door onto elite Florentine culture and express prevailing opinions on concepts such as love, beauty and fidelity.

In addition, they offer a wide-ranging survey of traditions, values and social ideals, as well as revealing the taste for the ornate and the refinement characteristic of late 15th-century, Florentine patrician society. In addition to the details of her wedding, a wealth of information survives on Giovanna’s short but intense life, recorded in a variety of sources, including the Ricordi - a sort of diary - written by her father, Maso di Luca. Recently rediscovered, it offers a glimpse of family life at the period. Her account books with annotations on movements of money and goods, for example, those relating to the wedding, also provide detailed information on Giovanna’s life.

Domenico Ghirlandaio | The Adoration of the Magi |

|

Domenico Ghirlandaio, Adoration of the Three Kings (Adoration of the Magi), 1487, Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Female portraits by Domenico Ghirlandaio

|

Domenico Ghirlandaio’s talents as a portraitist were praised by Vasari, who singled out his ability to capture the model’s features in a realistic manner. Together with his workshop assistants, Ghirlandaio was responsible for a group of portraits that display a great variety of representational choices. Many of these works are innovative in composition and stylistic approach. The influence of Flemish art, in particular that of Hans Memling, is evident in the female likeness at the Lindenau Museum. The Portrait of Selvaggia Sassetti, probably conceived by Domenico but executed by his younger brother David, highlights the presence of the sitter, whose gaze is directed in a straight line towards the viewer. Instead the fine Portrait of a Young Woman, from the Museu Calouste Gulbenkian, evokes a more poetic atmosphere. In the case of the Portrait of Giovanna degli Albizzi Tornabuoni, Domenico Ghirlandaio was personally responsible for both the conception of the portrait and its execution. Ghirlandaio communicates the sitter’s grace and captivating dignity in a highly effective manner. For the portrait of Giovanna the painter deliberately employed the traditional profile pose.

|

Portrait of Selvaggia Sassetti, ca. 1487–88

|

Many commentators on this portrait observed that the sitter appears to be the same person as the girl standing behind the kneeling girl in the fresco of the Resurrection of the Boy in the Sassetti Chapel in the church of Santa Trinità, Florence. She is one of Sassetti's seven daughters, Selvaggia Margharita (born in 1470). Her wedding in 1488 seems to be the most likely occasion for commissioning the portrait, in which she is more mature than she is in the fresco that was painted three years earlier.

Domenico Ghirlandaio | The Sassetti Chapel in the Santa Trinita church in Florence

|

|

Domenico Ghirlandaio, and a workshop assistant, possibly David Ghirlandaio, Portrait of Selvaggia Sassetti, New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Domenico Ghirlandaio, and a workshop assistant, possibly David Ghirlandaio, Portrait of Selvaggia Sassetti, New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

|

Portrait of a Young Woman, ca. 1490–94

|

|

|

| The young woman portrayed is reminiscent of the artist’s frescoes depicting the female members of the Sassetti family in one of the chapels of Santa Trinità in Florence. She is dressed in the Florentine fashion of that time, wearing layers of tight-fitting clothes and a coral necklace to decorate the neckline.

The luminosity and freshness of the subject, dressed in a red Florentine gown and wearing a coral necklace, is handled with a realism and naturalism typical of the last quarter of the Fifteenth century.

Like Botticelli’s images of females, those by Ghirlandaio reveal an aesthetic compromise that emphasises an idealistic stylisation and the decorative harmony of the whole. This style appeared at a time when portraits were spreading among the bourgeoisie and there was a growing taste for realistic characterisation of figures, which corresponded to a general trend towards humanising art. Ghirlandaio managed to create a local atmosphere by maintaining a type of figure that did not show excessive concern for detail. This style developed from frescoes and was inherited from the previous century.[2] |

|

Domenico Ghirlandaio and workshop, Portrait of a Young Woman, ca. 1490–94, Lisbon, Museu Calouste Gulbenkian

|

Portrait of Lucrezia Tornabuoni, about 1475

|

|

|

The sitter resembles a young woman in the frescoes painted by Ghirlandaio for Francesco Sassetti in the church of Santa Trinita, Florence. She has been plausibly identified as Sibilla, the eldest of Sassetti's daughters.

Gert Jan van der Sman (in Ghirlandaio y el Renacimiento en Florencia. Exhibition catalogue, Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, 2010) accepts the identification of the sitter as Selvaggia Sassetti and dates the picture about 1487–88. He calls it a "spin-off" from the commission of the fresco cycle in the Sassetti chapel and places it within "a group of independent portraits made under the supervision of Ghirlandaio in close collaboration with an assistant, possibly David".[3] |

|

Portrait of Lucrezia Tornabuoni, attributed to Domenico Ghirlandaio, about 1475, Washington, National Gallery of Art |

Art in Tuscany | Domenico Ghirlandaio

Giorgio Vasari's Lives of the Artists | Domenico Ghirlandaio, painter of Florence

Virtue and Beauty: Leonardo's "Ginevra de' Benci" and Renaissance Portraits of Women | The exhibition surveyed the phenomenal rise of female portraiture in Florence from c. 1440 to c. 1540 and was on view in the West Building of the National Gallery of Art from 30 September 2001 through 6 January 2002.

Ghirlandaio and Renaissance Florence at Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza | www.museothyssen.org

Portrait of a Young Woman | Museu Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisboa | www.museu.gulbenkian.pt

[1] Ghirlandaio and Renaissance Florence' | Domenico Ghirlandaio’s Portrait of Giovanna degli Albizzi Tornabuoni has traditionally been the iconic image that represents the Old Master Paintings collection of the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza. An absolute masterpiece within the artist’s oeuvre and within Florentine art, it perfectly and beautifully reflects Renaissance ideals of the last quarter of the fifteenth century.

Giovanna, born on 18 December 1468, was the eighth daughter of Maso di Luca degli Albizzi and Caterina Soderini. She received the type of education considered appropriate for young women of her social status. The most important event in Giovanna’s life was her marriage to Lorenzo Tornabuoni (1468–1497), heir to an influential family with links to the Medici. Their wedding was celebrated in September 1486: the festivities were most lavish and for three days the beautiful Giovanna held centre stage. On 11 October 1487 the young couple’s first child, Giovannino, was born, but tragically, Giovanna died aged nineteen during her second pregnancy the following year. She was buried in the church of Santa Maria Novella on 7 October 1488.

Giovanna has been preserved for posterity by Domenico Ghirlandaio, who around 1489 received the commission for a posthumous portrait intended to hang permanently in a place of honour in the Palazzo Tornabuoni. The painting and its wider context are the focus of the present exhibition at the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza. Notably, Ghirlandaio emphasised three aspects of the sitter’s personality — her beauty, her role as the wife of Lorenzo, and her virtue and devoutness.

"Behind every work of art there lies a story. Naturally, the older the work the more difficult it is to trace these stories, and this is particularly the case with most Quattrocento paintings, for which documentation is sparse. Domenico Ghirlandaio's Portrait of Giovanna degli Albizzi Tornabuoni is a notable exception to this rule. There is no mystery to the identity of the portrait's subject, and its original location is well documented.

(...) From early on, Giovanna's grandfather, Luca di Maso degli Albizzi (1382-1458), distanced himself from his older brother Rinaldo and allied himself with the Medici. Luca's worldly goods had remained exempt from the devastating confiscation meted out to his brother in 1434. Luca distinguished himself as the captain of the Florentine Galleys and travelled extensively throughout most of Europe. He married twice. His first wife was Lisabetta di Niccolo' de' Bardi, with whom he was espoused between 1410 and 1425. His second wife, Aurelia di Niccola de' Medici, belonged to a lesser branch of the Medici family. Aurelia bore him six children. The first-born, Maso di Luca (1426-1491), would also marry twice, and it was from his second marriage that Giovanna was born.

(...) Giovanna degli Albizi, noted for her heavenly beauty, who married Lorenzo Tornabuoni, cousin of Lorenzo the Magnificent, when she was 17 years old. Lorenzo's father, Giovanni di Francesco Tornabuoni, had accumulated great wealth as the manager of the Rome branch of the Medici bank, in addition to acting as the intermediary between the Medici and the pope on numerous occasions. In Florence, Giovanni Tornabuoni established himself as a lover and patron of the arts by first enlarging the family palace and providing it with an imposing façade, and subsequently having the Cappella Maggiore of the church of Santa Maria Novella decorated by Domenico Ghirlandaio. Giovanni had all the means at his disposal to ensure that Lorenzo, his only legitimate son, would become a person well versed in a broad range of subjects and interests and a successful businessman, in accordance with the humanist ideal of the Renaissance man. After Giovanni's sister Lucrezia (1427-1482) married Piero di Cosimo de' Médici (1416-1469) in 1444, the Tornabuoni found themselves in a very favourable position on the social ladder.

Named after his cousin Lorenzo il Magnifico (1448-1492), who was at this time the most powerful man in Florence.

(...) The documentation of the marriage of Lorenzo and Giovanna is more extensive than is usual. Although no notarial deeds have been preserved, the absence of these is fully compensated for by other sources. One exceptional record comes in the form of a celebratory nuptial poem, known as an epithalamium, composed by the humanist Naldo Naldi; it will be regularly cited in this catalogue. The tradition of recording the splendours of a wedding in this kind of literary form was much more in line with the more courtly North Italian culture than the world of the Florentine mercantile aristocracy and further illustrates the princely tastes and lofty ambitions of the Tornabuoni, both father and son. (...)"

[2] Calouste Sarkis Gulbenkian was an Armenian businessman and philanthropist. He played a major role in making the petroleum reserves of the Middle East available to Western development. By the end of his life he had become one of the world's wealthiest individuals and his art acquisitions considered one of the greatest private collections.

Calouste Gulbenkian revealed his passion for art at an early age. This reflected his origins in Cappadocia — a major crossroads of religions and art--and Constantinople — another crossroads of civilizations and the capital of the Romans, Greeks, and Ottoman Turks. Throughout his life, he assembled an eclectic and unique collection that was influenced by his travels and his personal taste. Calouste Gulbenkian's collection of paintings includes works by Bouts, Van de Weyden, Lochner, Cima de Conegliano, Carpaccio, Rubens, Van Dyck, Frans Hals, Rembrandt, Guardi, Gainsborough, Romney, Lawrence, Fragonard, Corot, Renoir, Nattier, Boucher, Manet, Degas and Monet. A favourite sculpture of his was the marble original of Houdon's famous Diana, which had belonged to Catherine of Russia and which Gulbenkian purchased from the Hermitage Museum in 1930.

The collection grew over the years. The Paris collection was divided for security reasons and part was sent to London. In 1936, the collection of Egyptian art was entrusted to the care of the British Museum while the finest paintings went to the National Gallery. Later, in 1948 and 1950, the same works would be sent on to the National Gallery of Art in Washington.

As his collection grew, Gulbenkian grew more concerned about how to preserve his achievement but also how to avoid paying taxes on his legacy. In 1937 he started discussions with Kenneth Clark, who had advised him in assembling his collection, about a “Gulbenkian Institute” at the National Gallery in London. However he was declared an “enemy under the act” by the British Government during the Second World War because he had followed the French Government to Vichy as a member of the Persian diplomatic delegation. The British temporarily confiscated his share of the oil from the Iraq Petroleum Company. Although this was a technical legal decision--and after the war the concession was returned to him with compensation--this action of his adopted country irritated him as he suspected that his partners were using the British Government to squeeze him out of the partnership.

Consequently he then considered the National Gallery of Art in Washington as a potential home for his collection and in 1943 Lord Radcliffe, his British lawyer, became his chief discussion partner and confidante. At the time of his death Gulbenkian does not appear to have decided where he wanted his collection to be housed and finally left it to Radcliffe to decide. However it was clear that Gulbenkian wanted his collection brought together under one roof where people could appreciate what one man could achieve in his lifetime.

After his death, arduous negotiations with the French Government and the National Gallery in Washington ensued. In 1960, the entire collection was brought to Portugal, where it was exhibited at the Palace of the Marquises of Pombal (Oeiras) from 1965 to 1969. Fourteen years after the death of this illustrious collector his wish was fulfilled, when the Calouste Gulbenkian Museum-specially built to house his collection-opened in Lisbon.

[3] Bernard Berenson (in a letter to Michael Friedsam. June 16, 1924), attributes it to Domenico Ghirlandaio, identifies the sitter as the lady whose portrait appears in the fresco of Saint Francis Raising the Dead Child, in the chapel of the Sassetti family in the church of the Santa Trinita, Florence. |

|

|

| |

|

Holiday accomodation in Tuscany | Podere Santa Pia | Artist and writer's residency

|

|

|

. |

|

|

Podere Santa Pia |

|

Podere Santa Pia, garden view, April |

|

View from Podere Santa Pia

on the coast and Corsica |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bagni San Filippo |

|

Arcidosso

|

|

Montalcino |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The façade and the bell tower of

San Marco in Florence |

|

Montefalco |

|

Florence, Duomo |

| |

|

|

|

|

The Church of Ognissanti was founded in 1251 by the Ordine degli Umiliati, rationalized the organization of the hamlet located on the site (it was outside the city walls at the time), which was specialized in woolworking.

Completely rebuilt in 1627 by B. Pettirossi, the church was completely restored following the damage caused by the 1966 flood. The façade done by Matteo Nigetti in 1637 is one of the earliest examples of Florentine Baroque; it was restored in 1872. The interior is a single nave with a sumptuously decorated transept.

Formerly in the sacristy for 84 years, Giotto's monumental Crucifix is now back in the Florentine church for which it was painted in 1310-1315, after a careful 8-year long restoration by the Opificio delle pietre dure (OPD).

The niches, in the church, are decorated with two frescoes referring to water: Sarah at Jacob's pit and Moses who makes water gush from the rock, two 17th century works by Giuseppe Romei.

The central fresco, which entirely covers the wall (8.10 x 4 m), is the work of Domenico Ghirlandaio (1449-1494), who produced with this work one of the best examples of his art, representing a serene yet dramatic episode of the Last Supper: the apostles are painted in the moment in which Jesus announces that one of them will betray him.

Following the requests of the monks who commissioned the painting, Ghirlandaio picked out a large number of apparently decorative details, which are in reality a precise symbolic reference to the drama of the Passion and Redemption of Christ, as for instance the evergreen plants, the flight of quails, the oranges, the cherries, the dove and the peacock.

By being a separate fresco, it can be compared to the style of the sinopite on the left wall.

Address: Via Borgognissanti 42 - Florence

Opening hours: 8:00-12:00/16:00-18:00

Art in Tuscany | Florence | Church of Ognissanti |

|

Church of Ognissanti Church of Ognissanti

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Church of Ognissanti

Church of Ognissanti