|

|

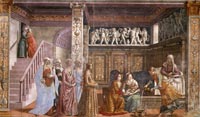

Domenico Ghirlandaio, The Expulsion of Joachim from the Temple (detail), fresco in the Cappella Tornabuoni, Santa Maria Novella, Firenze |

|

|

| Domenico di Tommaso del Ghirlandajo, who, from his talent and from the greatness and the vast number of his works, may be called one of the most important and most excellent masters of his age, was made by nature to be a painter; and for this reason, in spite of the opposition of those who had charge of him (which often nips the finest fruits of our intellects in the bud by occupying them with work for which they are not suited, and by diverting them from that to which nature inclines them), he followed his natural instinct, secured very great honour for himself and profit for his art and for his kindred, and became the great delight of his age. He was apprenticed by his father to his own art of goldsmith, in which Tommaso was a master more than passing good, for it was he who made the greater part of the silver votive offerings that were formerly preserved in the press of the Nunziata, and the silver lamps of the chapel, which were all destroyed in the siege of the city in the year 1529. Tommaso was the first who invented and put into execution those ornaments worn on the head by the girls of Florence, which are called ghirlande;[23] whence he gained the name of Ghirlandajo, not only because he was their first inventor, but also because he made an infinite number of them, of a beauty so rare that none appeared to please save such as came out of his shop. Being thus apprenticed to the goldsmith's art, but taking no pleasure therein, he was ever occupied in drawing. Endowed by nature with a perfect spirit and with an admirable and judicious taste in painting, although he was a goldsmith in his boyhood, yet, by devoting himself[Pg 220] ever to design, he became so quick, so ready, and so facile, that many say that while he was working as a goldsmith he would draw a portrait of all who passed the shop, producing a likeness in a second; and of this we still have proof in an infinite number of portraits in his works, which show a most lifelike resemblance. His first pictures were in the Chapel of the Vespucci in Ognissanti, where there is a Dead Christ with some saints, and a Misericordia over an arch, in which is the portrait of Amerigo Vespucci, who made the voyages to the Indies; and in the refectory of that place he painted a Last Supper in fresco. In S. Croce, on the right hand of the entrance into the church, he painted the Story of S. Paulino; wherefore, having acquired very great fame and coming into much credit, he painted a chapel in S. Trinita for Francesco Sassetti, with stories of S. Francis. This work was admirably executed by him, and wrought with grace, lovingness, and a high finish; and he counterfeited and portrayed therein the Ponte a S. Trinita, with the Palace of the Spini. On the first wall he depicted the story of S. Francis appearing in the air and restoring the child to life; and here, in those women who see him being restored to life—after their sorrow for his death as they bear him to the grave—there are seen gladness and marvel at his resurrection. He also counterfeited the friars issuing from the church behind the Cross, together with some grave-diggers, to bury him, all wrought very naturally; and there are likewise other figures marvelling at that event which give no little pleasure to the eye, among which are portraits of Maso degli Albizzi, Messer Agnolo Acciaiuoli, and Messer Palla Strozzi, eminent citizens often cited in the history of the city. On another wall he painted S. Francis, in the presence of the vicar, renouncing his inheritance from his father, Pietro Bernardone, and assuming the habit of sackcloth, which he is girding round him with the cord. On the middle wall he is shown going to Rome and having his Rule confirmed by Pope Honorius, and presenting roses in January to that Pontiff. In this scene he depicted the Hall of the Consistory, with Cardinals seated around, and certain steps ascending to it, furnishing the flight of steps with a balustrade, and painting there some half-length figures portrayed from the life, among which is the portrait of the[Pg 221] elder Lorenzo de' Medici, the Magnificent; and there he also painted S. Francis receiving the Stigmata. In the last he made the Saint dead, with his friars mourning for him, among whom is one friar kissing his hands—an effect that could not be rendered better in painting; not to mention that a Bishop in full robes, with spectacles on his nose, is chanting the prayers for the dead so vividly, that only the lack of sound shows him to be painted. In one of two pictures that are on either side of the panel he portrayed Francesco Sassetti on his knees, and in the other his wife, Monna Nera, with their children (but these last are in the aforesaid scene of the child being restored to life), and with certain beautiful maidens of the same family, whose names I have not been able to discover, all in the costumes and fashions of that age, which gives no little pleasure. Besides this, he made four Sibyls on the vaulting, and an ornament above the arch on the front wall without the chapel, containing the scene of the Tiburtine Sibyl making the Emperor Octavian adore Christ, which is executed in a masterly manner for a work in fresco, with much vivacity and loveliness in the colours. To this work he added a panel wrought in distemper, also by his hand, containing a Nativity of Christ that should amaze any person of understanding, wherein he portrayed himself and made certain heads of shepherds, which are held to be something divine. Of this Sibyl and of other parts of this work there are some very beautiful drawings in our book, made in chiaroscuro, and in particular the view in perspective of the Ponte a S. Trinita. For the Frati Ingesuati he painted a panel for their high-altar, with certain Saints kneeling—namely, S. Giusto, Bishop of Volterra, who was the titular Saint of that church; S. Zanobi, Bishop of Florence; an Angel Raphael; a S. Michael, clad in most beautiful armour; and other saints. For this work Domenico truly deserves praise, for he was the first who began to counterfeit with colours certain trimmings and ornaments of gold, which had not been done up to that time; and he swept away in great measure those borders of gilding that were made with mordant or with bole, which were more suitable for church-hangings than for the work of good masters. More beautiful than all the other figures is the Madonna, who has the Child in her arms and four little angels[Pg 222] round her. This panel, which is wrought as well as any work in distemper could be, was then placed in the church of those friars without the Porta a Pinti; but since that building, as will be told elsewhere, was destroyed, it is now in the Church of S. Giovannino, within the Porta S. Piero Gattolini, where there is the Convent of the aforesaid Ingesuati. In the Church of Cestello he painted a panel—afterwards finished by his brothers David and Benedetto—containing the Visitation of Our Lady, with certain most charming and beautiful heads of women. In the Church of the Innocenti he painted the Story of the Magi on a panel in distemper, which is much extolled. In this are heads most beautiful in expression and varied in features, both young and old; and in the head of Our Lady, in particular, are seen all the dignity, beauty, and grace that art can give to the Mother of the Son of God. On the tramezzo[24] of the Church of S. Marco there is another panel, with a Last Supper in the guest-room, both executed with diligence; and in the house of Giovanni Tornabuoni there is a round picture with the Story of the Magi, wrought with diligence. In the Little Hospital, for the elder Lorenzo de' Medici, he painted the story of Vulcan, in which many nude figures are at work with hammers making thunderbolts for Jove. And in the Church of Ognissanti in Florence, in competition with Sandro di Botticello, he painted a S. Jerome in fresco (which is now beside the door that leads to the choir), surrounding him with an infinite number of instruments and books, such as are used by the learned. The friars having occasion to remove the choir from the place where it stood, this picture, together with that of Sandro di Botticello, has been bound round with irons and transported without injury into the middle of the church, at the very time when these Lives are being printed for the second time. He also painted the arch over the door of S. Maria Ughi, and a little shrine for the Guild of Linen-Manufacturers, and likewise a very beautiful S. George, slaying the Dragon, in the same Church of Ognissanti. And in truth he had a very good knowledge of the method of painting on walls, which he did with very great facility, although he was scrupulously careful in the composition of his works. |

Domenico Ghirlandaio, Death of St. Francis |

||

|

||

Domenico Ghirlandaio, Death of St. Francis, 1482-1485, Cappella Sassetti, Santa Trinità, Florence |

||

Being then summoned to Rome by Pope Sixtus IV to paint his chapel, in company with other masters, he painted there Christ calling Peter and Andrew from their nets, and the Resurrection of Jesus Christ, the greater part of which has since been spoilt in consequence of being over the door, on which it became necessary to replace an architrave that had fallen down. There was living in Rome at this same time Francesco Tornabuoni, a rich and honoured merchant, much the friend of Domenico. This man, whose wife had died in childbirth, as is told in the Life of Andrea Verrocchio, desiring to honour her as became their noble station, had caused a tomb to be made for her in the Minerva; and he also wished Domenico to paint the whole wall against which this tomb stood, and likewise to make for it a little panel in distemper. On that wall, therefore, he painted four stories—two of S. John the Baptist and two of the Madonna—which brought him truly great praise at that time. And Francesco took so much pleasure in his dealings with Domenico, that, when the latter returned to Florence rich in honour and in gains, Francesco recommended him by letters to his relative Giovanni, telling him how well the painter had served him in that work, and how well satisfied the Pope had been with his pictures. Hearing this, Giovanni began to contemplate employing him on some magnificent work, such as would honour his own memory and bring fame and profit to Domenico. Now it chanced that the principal chapel of S. Maria Novella (a convent of Preaching Friars), formerly painted by Andrea Orcagna, was injured in many parts by rain in consequence of the roof of the vaulting being badly covered. For this reason many citizens had wished to restore it, or rather, to have it painted anew; but the owners, who belonged to the family of the Ricci, had never consented to this, being unable to bear so great an expense themselves, and unwilling to allow others to do so, lest they should lose the rights of ownership and the distinction of the arms handed down to them by their ancestors. Giovanni, then, being desirous that Domenico should make him his memorial there, set to work in this matter, trying various ways; and finally he promised the Ricci to bear the whole expense himself, to give them some sort of recompense, and to have their arms placed in the most conspicuous and honourable place in that[Pg 224] chapel. And so they came to an agreement, making a contract in the form of a very precise instrument according to the terms described above. Giovanni allotted this work to Domenico, with the same subjects as were painted there before; and they agreed that the price should be 1,200 gold ducats of full weight, with 200 more in the event of the work giving satisfaction to Giovanni. Thereupon Domenico put his hand to the work and laboured without ceasing for four years until he had finished it—which was in 1485—to the very great satisfaction and contentment of Giovanni, who, while admitting that he had been well served, and confessing ingenuously that Domenico had earned the additional 200 ducats, said that he would be pleased if he would be satisfied with the original price. And Domenico, who esteemed glory and honour much more than riches, immediately let him off all the rest, declaring that he set much greater store on having given him satisfaction than on the matter of complete payment. Giovanni afterwards caused two large coats of arms to be made of stone—one for the Tornaquinci and the other for the Tornabuoni—and placed on the pilasters without the chapel, and in the arch he placed other arms belonging to that family, which is divided into various names and various arms—namely, in addition to the two already mentioned, those of the Ghiachinotti, Popoleschi, Marabottini, and Cardinali. And afterwards, when Domenico painted the altar-panel, he caused to be placed in the gilt ornament, under an arch, as a finishing touch to that panel, a very beautiful Tabernacle of the Sacrament, on the frontal of which he made a little shield a quarter of a braccio in length, containing the arms of the said owners—that is, the Ricci. And a fine jest it was at the opening of the chapel, for these Ricci looked for their arms with much ado, and finally, not being able to find them, went off to the Tribunal of Eight, contract in hand. Whereupon the Tornabuoni showed that these arms had been placed in the most conspicuous and most honourable part of the work; and although the others exclaimed that they were invisible, they were told that they were in the wrong, and that they must be content, since the Tornabuoni had caused them to be placed in so honourable a position as the neighbourhood of the most Holy Sacra[Pg 225]ment. And so it was decided by that tribunal that they should be left untouched, as they may be seen to-day. Now, if this should appear to anyone to be outside the scope of the Life that I have to write, let him not be vexed, for it all flowed naturally from the tip of my pen. And it should serve, if for nothing else, at least to show how easily poverty falls a prey to riches, and how riches, if accompanied by discretion, achieve without censure anything that a man desires. |

||

|

||

|

||

Domenico Ghirlandaio, Announcement of Death to St Fina, 1473-75, fresco, Collegiata, San Gimignano |

||

But to return to the beautiful works of Domenico; in that chapel, first of all, are the four Evangelists on the vaulting, larger than life; and, on the window-wall, stories of S. Dominic, S. Peter Martyr, S. John going into the Desert, the Madonna receiving the Annunciation from the Angel, and many patron saints of Florence on their knees above the window; while at the foot, on the right hand, is a portrait from life of Giovanni Tornabuoni, with one of his wife on the left, which are both said to be very lifelike. On the right-hand wall are seven scenes—six below, in compartments as large as the wall allows, and the last above, twice as broad as any of the others and bounded by the arch of the vaulting; and on the left-hand wall are also seven scenes from the life of S. John the Baptist. The first on the right-hand wall is the Expulsion of Joachim from the Temple, wherein patience is depicted in his countenance, with that contempt and hatred in the faces of the others which the Jews felt for those who came to the Temple without having children. In this scene, in the part near the window, are four men portrayed from life, one of whom, old, shaven, and wearing a red cap, is Alesso Baldovinetti, Domenico's master in painting and in mosaic. Another, bareheaded, who is holding one hand on his side and is wearing a red mantle, with a blue garment below, is Domenico himself, the master of the work, who portrayed himself in a mirror. The one who has long black locks and thick lips is Bastiano da San Gimignano, his disciple and brother-in-law; and the last, who has his back turned, with a little cap on his head, is the painter David Ghirlandajo, his brother. All these are said, by those who knew them, to be truly vivid and lifelike portraits. In the second scene is the Nativity of Our Lady, executed with great diligence, and, among other notable things that he painted therein, there is in the[Pg 226] building (drawn in perspective) a window that gives light to the room, which deceives all who see it. Besides this, while S. Anna is in bed, and certain ladies are visiting her, he painted some women washing the Madonna with great care—one is getting ready the water, another is preparing the swaddling-clothes, a third is busy with some service, a fourth with another, and, while each is attending to her own duty, another woman is holding the little child in her arms and making her laugh by smiling at her, with a womanly grace truly worthy of such a work; besides many other expressions that are in each figure. In the third, which is above the first, is the Madonna ascending the steps of the Temple, with a building which recedes from the eye correctly enough, in addition to a nude figure that brought him praise at that time, when few were to be seen, although it had not that complete perfection which is shown by those painted in our own day, for those masters were not as excellent as ours. Next to this is the Marriage of Our Lady, wherein he represented the unbridled rage of those who are breaking their rods because they do not blossom like that of Joseph; and this scene has an abundance of figures in an appropriate building. In the fifth are seen the Magi arriving in Bethlehem with a great number of men, horses, and dromedaries, and a variety of other things—a scene truly well composed. Next to this is the sixth, showing the impious cruelty practised by Herod against the Innocents, wherein there is seen a most beautiful combat between women and soldiers, with horses that are striking and driving them about; and in truth this is the best of all the stories that are to be seen by his hand, for it is executed with judgment, intelligence, and great art. There may be seen therein the impious resolution of those who, at the command of Herod, without regard for the mothers, are slaying those poor infants, among which is one, still clinging to the breast, that is dying from wounds received in its throat, so that it is sucking, not to say drinking, as much blood as milk from that breast—an effect truly natural, and, being wrought in such a manner as it is, able to kindle a spark of pity in the coldest heart. There is also a soldier who has seized a child by force, and while he runs off with it, pressing it against his breast to kill it, the mother is seen hanging from his hair in[Pg 227] the utmost fury, and forcing him to bend his back in the form of an arch, so that three very beautiful effects are shown among them—one in the death of the child, which is seen expiring; the second in the impious rage of the soldier, who, feeling himself drawn backwards so strangely, is shown in the act of avenging himself on the child; and the third is that the mother, seeing the death of her babe, is seeking with fury, grief, and disdain to prevent the villain from going off scathless; and the whole is truly more the work of a philosopher admirable in judgment than of a painter. There are many other emotions depicted, which will demonstrate to him who studies them that this man was without doubt an excellent master in his time. Above this, in the seventh scene, which embraces the space of two, and is bounded by the arch of the vaulting, are the Death and the Assumption of Our Lady, with an infinite number of angels, and innumerable figures, landscapes, and other ornaments, of which he used to paint an abundance in his facile and practised manner. |

||

|

||

Domenico Ghirlandaio, The Birth of the Baptist |

||

|

||

Domenico Ghirlandaio, The Birth of the Baptist, fresco in the Cappella Tornabuoni, Santa Maria Novella, Firenze |

||

On the other wall are stories of S. John, and in the first is Zacharias sacrificing in the Temple, when the Angel appears to him and makes him dumb for his unbelief. In this scene, showing how sacrifices in temples are ever attended by a throng of the most distinguished men, and wishing to make it as honourable as he was able, he portrayed a good number of the Florentine citizens who then governed that State, particularly all those of the house of Tornabuoni, both young and old. Besides this, in order to show that his age was rich in every sort of talent, above all in learning, he made a group of four half-length figures conversing together at the foot of the scene, representing the most learned men then to be found in Florence. The first of these, who is wearing the dress of a Canon, is Messer Marsilio Ficino; the second, in a red mantle, with a black band round his neck, is Cristofano Landino; the figure turning towards him is Demetrius the Greek; and he who is standing between them, with one hand slightly raised, is Messer Angelo Poliziano; and all are very lifelike and vivacious. In the second scene, next to this, there follows the Visitation of Our Lady to S. Elizabeth, with a company of many women dressed in costumes of those times, among whom is a portrait of Ginevra de' Benci, then a most beautiful maiden. In the[Pg 228] third, above the first, is the birth of S. John, wherein there is a very beautiful scene, for while S. Elizabeth is lying in bed, and certain neighbours come to see her, and the nurse is seated suckling the infant, one woman is joyfully demanding it from her, that she may show to the others what an unexampled feat the mistress of the house has performed in her old age. Finally, there is a woman, who is very beautiful, bringing fruits and flasks from the country, according to the Florentine custom. In the fourth scene, next to this, is Zacharias, still dumb, marvelling—but with undaunted heart—that this child should have been born to him; and while they keep asking him about the name, he is writing on his knee, with his eyes fixed on his son, whom a woman who has knelt down before him is holding reverently in her arms, and he is tracing with his pen on the paper, "John shall be his name," to the no little marvel of many other figures, who appear to be in doubt whether the thing be true or not. There follows in the fifth his preaching to the multitude, in which scene there is shown that attention which the populace ever gives when hearing new things, particularly in the heads of the Scribes, who, while listening to John, appear from a certain expression of countenance to be deriding his law, and even to hate it; and there are seen many men and women, variously attired, both standing and seated. In the sixth S. John is seen baptizing Christ, in whose reverent expression Domenico showed very clearly the faith that should be placed in such a Sacrament. And since this did not fail to achieve a very great effect, he depicted many already naked and barefooted, waiting to be baptized, and revealing faith and willingness carved in their faces; and one among them, who is taking off his shoe, personifies readiness itself. In the last, which is in the arch next to the vaulting, are the sumptuous Feast of Herod and the Dance of Herodias, with an infinite number of servants performing various services in that scene; not to mention the grandeur of an edifice drawn in perspective, which proves the talent of Domenico no less clearly than do the other pictures. The panel, which stands by itself, he executed in distemper, as he did the other figures in the six pictures. Besides the Madonna, who is seated in the sky with the Child in her arms, and the other saints[Pg 229] who are round her, there are S. Laurence and S. Stephen, who are absolutely alive, with S. Vincent and S. Peter Martyr, who lack nothing save speech. It is true that a part of this panel remained unfinished in consequence of his death; but he had carried it so far on that there was nothing left to complete save certain figures on the back, where there is the Resurrection of Christ, with three figures in the other pictures, and the whole was afterwards finished by Benedetto and David Ghirlandajo, his brothers. This chapel was held to be a very beautiful work, grand, ornate, and lovely, through the vivacity of the colours, through the masterly finish in their application on the walls, and because very little retouching was done on the dry, not to mention the invention and the composition of the subjects. And in truth Domenico deserves the greatest praise on all accounts, particularly for the liveliness of the heads, which, being portrayed from nature, present to every eye most lifelike effigies of many distinguished persons. For the same Giovanni Tornabuoni, at his Villa of Casso Maccherelli, which stands on the River Terzolle at no great distance from the city, he painted a chapel which has since been half destroyed through being too near to the river; but the paintings, although they have been uncovered for many years, continually washed by rain and scorched by the sun, have remained so fresh that one might think they had been covered—so great is the value of working in fresco, when the work is done with care and judgment and not retouched on the dry. He also made many figures of Florentine Saints, with most beautiful adornments, in that hall of the Palace of the Signoria which contains the marvellous clock of Lorenzo della Volpaia. And so great was his love of working and of giving satisfaction to all, that he commanded his lads to accept any work that might be brought to his shop, even hoops for women's baskets, saying that if they would not do them he would paint them himself, to the end that none might leave the shop unsatisfied. But when household cares fell upon him he was troubled, and he therefore laid the charge of all expenditure on his brother David, saying to him, "Leave me to work, and do thou provide, for now that I have begun to understand the methods of this art, it grieves me that they will not commission[Pg 230] me to paint the whole circuit of the walls of the city of Florence with stories"; thus revealing a spirit absolutely invincible and resolute in every action. For S. Martino in Lucca he painted S. Peter and S. Paul on a panel. In the Abbey of Settimo, without Florence, he painted the wall of the principal chapel in fresco, with two panels in distemper in the tramezzo[25] of the church. In Florence, also, he executed many pictures, round, square, and of other kinds, which can only be seen in the houses of individual citizens. In Pisa he painted the recess behind the high-altar of the Duomo, and he worked in many parts of that city, painting, for example, on the front wall of the Office of Works, a scene of King Charles, portrayed from life, making supplication for Pisa; and two panels in distemper, that of the high-altar and another, for the Frati Gesuati in S. Girolamo. In that place there is also a picture of S. Rocco and S. Sebastian by the hand of the same man, which was given by one or other of the Medici to those fathers, who have therefore added to it the arms of Pope Leo X. He is said to have been so accurate in draughtsmanship, that, when making drawings of the antiquities of Rome, such as arches, baths, columns, colossea, obelisks, amphitheatres, and aqueducts, he would work with the eye alone, without rule, compasses, or measurements; and after he had made them, on being measured, they were found absolutely correct, as if he had used measurements. He drew the Colosseum by the eye, placing at the foot of it a figure standing upright, from the proportions of which the whole edifice could be measured; this was tried by some masters after his death, and found quite correct. Over a door of the cemetery of S. Maria Nuova he painted a S. Michael in fresco, clad in armour which reflects the light most beautifully—a thing seldom done before his day. At the Abbey of Passignano, a seat of the Monks of Vallombrosa, he wrought certain works in company with his brother David and Bastiano da San Gimignano. Here the two others, finding themselves poorly fed by the monks before the arrival of Domenico, complained to the Abbot, praying him to have them better[Pg 231] served, since it was not right that they should be treated like bricklayers' labourers. This the Abbot promised to do, saying in excuse that it was due more to the ignorance of the monks who looked after strangers than to malice. Domenico arrived, but everything continued just the same; whereupon David, seeking out the Abbot once again, declared with due apologies that he was not doing this for his own sake but on account of the merits and talents of his brother. But the Abbot, like the ignorant man that he was, made no other answer. That evening, then, when they had sat down to supper, up came the stranger's steward with a board covered with bowls and messes only fit for a hangman, exactly the same as before. Thereupon David, flying into a rage, upset the soup over the friar, and, seizing the loaf that was on the table, fell upon him with it and belaboured him in such a manner that he was carried away to his cell more dead than alive. The Abbot, who was already in bed, got up and ran to the noise, believing that the monastery was tumbling down; and finding the friar in a sorry plight, he began to upbraid David. Enraged by this, David bade him be gone out of his sight, saying that the talent of Domenico was worth more than all the pigs of Abbots like him that had ever lived in that monastery. Whereupon the Abbot, seeing himself in the wrong, did his utmost from that time onwards to treat them like the important men that they were. This work finished, Domenico returned to Florence, where he painted a panel for Signor di Carpi, sending another to Rimini for Signor Carlo Malatesta, who had it placed in his chapel in S. Domenico. The latter panel was in distemper, with three very beautiful figures, and with little scenes below; and behind were figures painted to look like bronze, with very great design and art. Besides these, he painted two panels for the Abbey of S. Giusto, a seat of the Order of Camaldoli, without Volterra; these panels, which are wondrously beautiful, he executed at the order of the Magnificent Lorenzo de' Medici, for the reason that the abbey was then held "in commendam" by his son Cardinal Giovanni de' Medici, who was afterwards Pope Leo. This abbey was restored not many years ago by the Very Reverend Messer Giovan Batista Bava of Volterra, who likewise held it "in commendam," to the said Congregation of Camaldoli.[Pg 232] |

||

| Being then summoned to Siena through the agency of the Magnificent Lorenzo de' Medici, Domenico undertook to adorn the façade of the Duomo with mosaics, Lorenzo acting as surety for him in this work to the extent of 20,000 ducats. And he began the work with much confidence and a better manner, but, being overtaken by death, he left it unfinished; even as, by reason of the death of the aforesaid Magnificent Lorenzo, there remained unfinished at Florence the Chapel of S. Zanobi, on which Domenico had begun to work in mosaic in company with the illuminator Gherardo. By the hand of Domenico is a very beautiful Annunciation in mosaic that is to be seen over that side-door of S. Maria del Fiore which leads to the Servi; and nothing better than this has yet been seen among the works of our modern masters of mosaic. Domenico used to say that painting was mere drawing, and that the true painting for eternity was mosaic. |  Mosaic depicting the Annunciation in the lunette above the Porta della Mandorla in the cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence |

|

A pupil of his, who lived with him in order to learn, was Bastiano Mainardi da San Gimignano, who became a very able master of his manner in fresco; wherefore he went with Domenico to San Gimignano, where they painted in company the Chapel of S. Fina, which is a beautiful work. Now the faithful and willing service of Bastiano, who acquitted himself very well, induced Domenico to judge him worthy to have a sister of his own for wife; and so their friendship was changed into relationship—a proof of liberality worthy of a loving master, who was pleased to reward the proficiency that his disciple had acquired by labouring at his art. Domenico caused the said Bastiano to paint a Madonna ascending into Heaven in the Chapel of the Baroncelli and Bandini in S. Croce (although he made the cartoon himself), with S. Thomas below receiving the Girdle—a beautiful work in fresco. |

Bastiano Mainardi, Assumption of the Virgin with the Gift of the Girdle, f resco, Santa Croce, Florence This monumental wall painting is in the Cappella Baroncelli in Santa Croce, Florence. According to Vasari it is the work of Bastiano Mainardi, but it is based on preliminary studies and cartoons by Domenico Ghirlandaio. |

|

[1] After about seven years of writing, Vasari, considered the first art historian and often referred to as the “father of art history”, published his most famous book, Le vite de più eccellenti architetti, pittori, et scultori in 1550. The printer was the Florentine humanist Lorenzo Torrentino (d. 1563). The two-volume, octavo work was dedicated to Cosimo de’ Medici. After its appearance several other biographies of artists appeared, most notably the life of Michelangelo by Asconio Condivi (q.v.). Vasari corrected and enlarged his text, issuing a second edition in 1568. It is this version that all subsequent editions and translations are based, and for which Vasari owes his fame. The work is divided into a preface (proemio), a discussion of the various media, and then three sections devoted to artist biographies arranged chronologically. The first section covers Cimabue to Lorenzo di Bicci, section two from Jacopo della Quercia to Pietro Perugino, and the final section, from Leonardo da Vinci to Michelangelo. Michelangelo was the only artist still living when the Vite appeared. Vasari ends with a section to ‘artists and readers’. Several indexes complete the work. |

||||

Art in Tuscany | Domenico Ghirlandaio | Frescoes in Sant'Andrea a Brozzi, San Donnino | The Tornabuoni Chapel | | Portrait of Giovanna degli Albizzi Tornabuoni | The Adoration of the Magi | Domenico Ghirlandaio, The Sassetti Chapel in the Santa Trinita church in Florence | Domenico Ghirlandaio, Calling of the Apostles, 1481, fresco in the Cappella Sistina | Domenice Ghirlandaio, Last Supper frescoes Giorgio Vasari | Lives of the Most Eminent Painters Sculptors and Architects Art in Tuscany | Art in Tuscany | Giorgio Vasari | Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects |

||||

|

This article incorporates material from the Wikipedia article Domenico Ghirlandaio published under the GNU Free Documentation License. |

||||

Holiday accomodation in Tuscany | Podere Santa Pia | Artist and writer's residency |

||||

Podere Santa Pia |

Podere Santa Pia, garden view, December |

San Qurico d'Orcia |

||

|

||||

Villa Celsa near Florence |

Piazza della Santissima Annunziata in Florence |

Choistro dello Scalzo, Florence |

||

The façade and the bell tower of San Marco in Florence |

Piazza della Santissima Annunziata in Florence |

Florence, Duomo |

||