|

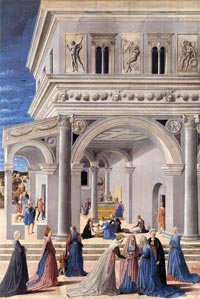

| Fra Carnevale, The Birth of the Virgi (detail), 1467, tempera and oil on wood, 145 x 96 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

Fra Carnevale | Birth of the Virgin and the Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple, 1467 |

The Birth of the Virgin is apparently a lateral panel from a highly original altarpiece commissioned in 1467 for the church of Santa Maria della Bella at Urbino. [1]

|

||

| This exceptionally rich painting has a companion in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the subject of which is usually identified as the Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple. The subjects, function, and authorship of the two panels have been much debated though recent scholarship makes it all but certain that they are the lateral panels of an altarpiece painted in 1467 for a lay confraternity of flagellants in the hospital church of Santa Maria della Bella in Urbino. The artist of that altarpiece was Fra Carnevale. Vasari [Ref. 1568] attests that the altarpiece was studied by the young Bramante, who was later to become the architect of Saint Peter's in Rome, and later sources assure us that in the seventeenth century it was confiscated by Cardinal Antonio Barberini, who in 1631 was papal legate to the city. In an inventory of Cardinal Antonio Barberini's possessions in Palazzo Barberini, Rome, drawn up in 1644 [Ref. Lavin 1975] we find the following descriptions of the panels in New York and Boston under numbers 13 and 14: "a painting on wood that shows a perspective with some women who greet each other . . . by Fra Carnevale," and "a similar painting that shows a perspective with some women on their way to church . . . by Fra Carnevale" ("Un quadro in tavola che rappresenta una prospettiva con alcune donne che s'incontrano, con cornice tinta di noce con un filetto d'oro, di mano di fra Carnovale per sopra finestra," and "Un quadro simile che rappresenta una prospettiva con alcune donne che vanno in chiesa, con cornice tinta di noce con un filetto d'oro, di mano di fra Carnovale"). From documents published by Carloni [Ref. 2005] we know that in 1632 the bishop of Urbino wrote to Cardinal Barberini to announce that the "prospettivi" had been sent to Rome in two crates. These must refer to the two panels from Santa Maria della Bella, for three months later payment was made to Claudio Ridolfi for a painting than can only have been the replacement of Fra Carnevale's altarpiece. That work shows the Birth of the Virgin (288 x 185 cm; now in the parish church of Groppello d'Adda), which presumably reflected the dedication of the altar. |

||

| What do we know about the church of Santa Maria della Bella? In 1565 the hospital buildings—including the small church of Santa Maria della Bella—were assigned to the nuns of the Convertite del Gesù, and it is possible that works of art were shifted about within the new convent [see Franco Mazzini, "Urbino, i mattoni e le pietre," Pesaro, 1999, pp. 421–22], confusing their original function. However, apart from Claudio Ridolfi's replacement altarpiece, the only other work certainly from the church (which had three altars) is a fresco of the Crucifixion painted by the late-Gothic Ferrarese artist Antonio Alberti in 1442 (Gallerie Nazionale, Urbino). What deserves consideration is the probability that the secular slant in the paintings is related to their setting in a confraternity oratory. If Fra Carnevale's approach to the subject of the New York panel may be described as oblique, in the Boston picture it is almost inscrutable. Despite the absence of any haloes, the picture is most often described as showing the Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple, which, according the "Golden Legend", took place when Mary was three years old. A good deal of license can be found in representations of the scene in the fifteenth century, but they all include Joachim, the Virgin's father, who is nowhere in sight in Fra Carnevale's painting. Moreover, instead of the traditional Jewish priest shown officiating at this event, Fra Carnevale shows three figures gathered at the high altar—apparently a Franciscan, possibly a Dominican or a friar wearing priestly robes, and a hooded figure—while two pilgrims are shown against the right-hand entrance pier. (Is one of these supposed to be Joachim or Joseph?) The remaining figures in the church are exclusively young males who chat, rest, or walk about. Two wear festive wreaths in their hair (one composed of roses, the other of leaves), while the coif of the young girl in blue is adorned with roses and a stem of rose leaves or myrtle. Kanter [Ref. 1994] reasonably suggested that the scene may show the marriage of the fourteen-year-old Virgin, imagined as an actual, fifteenth-century ceremony, with the prospective bride on her way to church, accompanied by her female relatives and two male guardians (once again, one of the women holds prayer beads). It is far easier to point out the anomalies in the depiction of this scene than it is to suggest an alternative subject. For this reason it is important to point out that the decorative reliefs on the church façade clearly depict events in the Virgin's life—the Annunciation and the Visitation—and that the three marble steps the young girl is about to climb are shown with fissures, as though to denote the passage from one age to another. Typically, this would be the transition from the era under the Law to that of Grace, but there is also the suggestion of the passage from a pagan past, symbolized by the dancing maenad and piping satyr on the bases of the columns and the classical urn with a branch protruding from its opening, to the Christian era, announced by the reliefs above the arches. There would thus seem to be no way around the religious content of both pictures, and the most probable identifications remain the Birth of the Virgin and the Presentation in the Temple or the Marriage of the Virgin. There is no basis for conjecturing that the pictures formed part of a larger series or cycle. Not only are the two panels the same size (neither has been cut down), but the scenes are constructed on a precisely mirror-image perspective grid, with the vanishing point located along the left edge of the New York panel and the right edge of the Boston panel, 62 centimeters from the bottom. In both, three stairs divide a foreground space from an interior one, viewed through a large, classical arch. The perspective must have been worked out on a separate piece of paper so that the results could be transferred to both panels by simply flipping the cartoon. The perspective grid was elaborated in greater detail in the New York panel—the incisions are clearly visible in the left background, where a mathematically determined diminution of the figures was wanted—but in both, pinpricks along the vertical edges indicating the transversals were carefully transposed [see Additional Views]. This sort of mirror-image type of construction would have made no sense if extended to further narrative panels, and it really only leaves open the possibility of a missing center element with a centralized perspective scheme. At the top of both panels are incisions marking off three arcs; in the Metropolitan panel these arcs are cusped. The frame thus had a Gothic profile, with small arches supported on consoles. This type of frame is found in numerous Marchigian altarpieces. The difference here is that they are aligned horizontally, as in an altarpiece by Paolo da Viso (Pinacoteca Civica, Ascoli Piceno). The type of frame indicated could have extended over a center panel or a niche containing a sculpture. As has long been acknowledged, architecture is the real protagonist of the compositions. In the New York panel the setting is a grand, secular palace bearing affinities with the Ducal Palace of Urbino. The character of the two ex-Barberini panels can, indeed, only be explained by the culture of the court of Urbino: of Federigo da Montefeltro, whose keen interest in architecture as well as in perspective is well known, and of his counselor-relative Ottaviano Ubaldini, who Giovanni Santi (Raphael's father) says painters and sculptors looked upon as a father. (Documents actually place Fra Carnevale in close touch with Ottaviano.) It is in this regard that the similarities of certain details in the panels with decorative elements in the palace become significant. The Montefeltro eagle that decorates the right hand spandrel of the palace in the New York panel is as though copied from the coat of arms above the fireplace of the Sala della Jole. The pseudo-antique reliefs bear a close, stylistic affinity with the bacchic frieze on that same fireplace, while the dolphin capitals of the column within the palace in the New York panel bear a striking similarity to those framing the main door into the Sala della Jole. Fra Carnevale's name occurs in a sixteenth-century list of engineers who had been employed on the Ducal Palace, along with Luciano Laurana and Francesco di Giorgio, and it has been forcefully argued that prior to 1468 and the appointment of Laurana as chief architect, the Dominican painter had a hand in the planning of the Sala della Jole [see Refs. Strauss 1979, pp. 136–41; and Borsi 1997, pp. 60–62). That he did architectural designs has received confirmation from a document of 1455 in which he is mentioned as the author of designs for capitals for the cathedral of Urbino. The ex-Barberini paintings only make sense if we think of them as addressed not only to the confraternity members but to Federico and Ottaviano.[2 |

||

|

||||

|

This article incorporates material from the Wikipedia article Fra Carnevale published under the GNU Free Documentation License. |

||||

|

||||

Podere Santa Pia |

Podere Santa Pia, garden view in April |

Sansepolcro |

||

|

||||

San Quirico d'Orcia |

Pienza |

Cortona |

||

Vasari Corridor, Florence |

Piazza della Santissima Annunziata in Florence |

Florence, Duomo |

||

| Santa Pia is located 3 km from Castigliocello Bandini, 15 km from Abazziia San 't Antimo and Montalcino, close to art cities like Siena, Pienza, Montepulciano and San Quirico d'Orcia, and 1 hour away from the seaside. Grosseto is Tuscany`s most southernly province and is considered to be the capital of Tuscan Maremma. Grosseto is the most southern Tuscan province. The town is situated about 12 kilometres from the sea, in the heart of Tuscan Maremma, a wide alluvial plain. In the past, the lake Prile spread over most of this territory. The lake has almost disappeared due to the drainage works undertaken in this area during the centuries. The various natural reserves surrounding Grosseto witness nonetheless Maremma`s past as a marshland. South of Grosseto flows the Ombrone, the most important river in southern Tuscany. At the river mouth there is the Parco dell`Uccellina. The ancient city walls built in 1574 under Grand Duke Francesco I de` Medici still surround its historical centre. Situated in a former marshland that was once infested with malaria, at present the province of Grosseto is a real paradise for those who love culture, nature and good cuisine. Grosseto countryside is scattered with ancient Etruscan towns, such as Roselle, Populonia and Vetulonia. Those who love nature can visit the Parco Naturale della Maremma (Maremma Natural Park), the Riserva Naturale Diaccia Botrona (Diaccia Botrona Nature Reserve) and the Parco Nazionale dell`Arcipelago Toscano (Tuscan Archipelago National Park) and spot some dolphins and whales in the Santuario dei Cetacei (Cetacea Sanctuary). Principina a Mare and Orbetello lagoon are renowned seaside resorts, whereas in the interior there is Saturnia with its famous spas. |

||||

|

||||

Monte Amiata and the surroundings of Podere Santa Pia |

||||