|

|

| I T

|

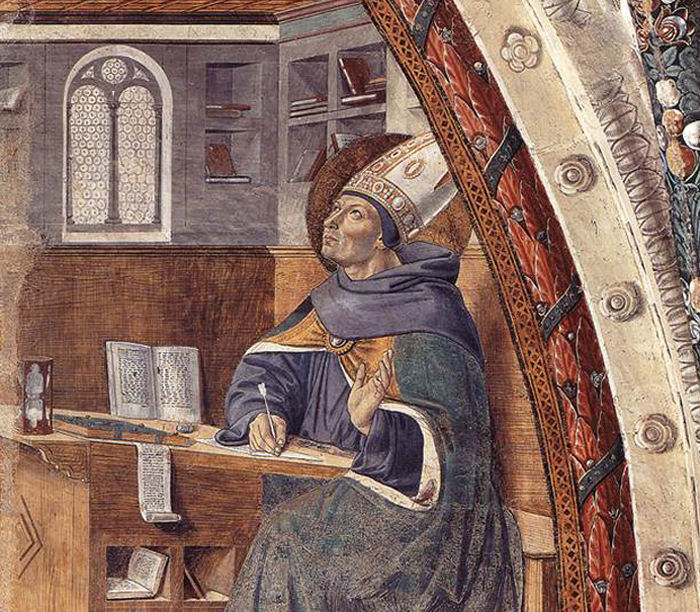

Benozzo Gozzoli, St Augustine Departing for Milan (scene 7, detail), 1464-65, fresco, 220 x 230 cm, Apsidal chapel, Sant'Agostino, San Gimignano |

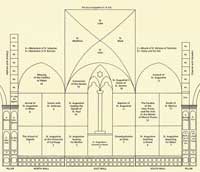

Benozzo Gozzoli | Fresco cycle in the apsidal chapel of Sant'Agostino, San Gimignano Sant'Agostino |

In 1464 Gozzoli left Florence for San Gimignano, where he executed some extensive works; in the church of Sant'Agostino, a composition of St. Sebastian protecting the City from the Plague of this same year, 1464; over the entire choir of the church, a triple course of scenes from the legends of St Augustine, from the time of his entering the school of Tegaste on to his burial, seventeen chief subjects, with some accessories; in the Pieve di San Gimignano, the Martyrdom of Sebastian, and other subjects, and some further works in the city and its vicinity. The church of Sant'Agostino in San Gimignano is a single-aisled hall church with three apsidal chapels and an open roof truss. It was built by the Augustinian canons between 1280 and 1298, and it represents a typical example of the Gothic architecture of the mendicant orders in central Italy. Benozzo Gozzoli, in collaboration with several assistants, produced here his main work, the decorations of the apsidal chapel of the church in 1464-65.[1] By 1463 at the latest, Benozzo had left his native city and moved to San Gimignano for four years, until 1467. He had left Florence because of the plague, for towns at higher altitudes such as San Gimignano were thought to be less at risk. Here, in collaboration with several assistants, he produced his main work, the decorations of the apsidal chapel of the church of Sant'Agostino (1464-65). The single-aisled hall church with three apsidal chapels and an open roof truss, built by the Augustinian canons between 1280 and 1298, is a typical example of the Gothic architecture of the mendicant orders in central Italy. Benozzo was given the commission by Fra Domenico Strambi, a learned Augustinian monk belonging to the monastery who in 1449 had been given a grant by the town to study theology at the Sorbonne in Paris. The paintings were produced within the contemporary context of the reformation of the monastery of Sant'Agostino. The intention was to merge it with the Augustinian order of San Salvatore in Lecceto near Siena. The choir, being the place where the community of monks assembled, was decorated with a didactic program of the life and work of St Augustine. The cycle of St Augustine is one of the main works of Tuscan narrative art dating from the middle of the century. It can take its place alongside the fresco cycle of the Legend of the True Cross (1453/54) by Piero della Francesca in Arezzo and Donatello's Passion Pulpit and Resurrection Pulpit (1460-62) in San Lorenzo in Florence. |

| The cycle depicts 17 scenes from the life of the Father of the Church. When selecting the scenes from the legend of St Augustine, Benozzo had to create his own iconography without using models, and Domenico Strambi helped him to achieve this. The distinguishing feature of the pictorial program is a simple construction of scenes which shows the protagonists in realistic rural, urban or architectural surroundings. The 17 pictures, which are arranged in three rows, use the traditional horizontal direction of reading, from the bottom left to the top right. Strambi is thought to be the author of the Latin inscriptions which comment on the events in each case. An innovation was the uniform system of architectural frames, in which painted pilasters separate each of the pictures from each other. It represents a direct preliminary stage to Domenico Ghirlandaio's painted wall structure of several loggia-like storeys. Benozzo arranged the life of St Augustine in three sections. In the lowest register he depicts the education, teachings and journeys of the saint. (1) The School of Tagaste, (2) St Augustine at the University of Carthage, (3) St Augustine Leaving his Mother, (4) St Augustine's Journey to Rome, (5) Disembarkation at Ostia, (6) St Augustine Teaching in Rome, (7) St Augustine Departing for Milan. The middle register shows his path to Christian faith: Finally, in the lunette fields the culmination of his journey through life appears. Here, as in Montefalco, the cycle is read from the bottom upwards, and as a result should be interpreted as a painted metaphor of a striving to reach God. (1) The School of Tagaste The middle register shows his path to Christian faith: Finally, in the lunette fields the culmination of his journey through life appears. (18) Frescoes of saints on the pillars |

||

|

||

The School of Tagaste (scene 1, north wall, detail), 1464-65, fresco, 220 x 230 cm, Apsidal chapel, Sant'Agostino, San Gimignano

|

||

| The first scene, The School of Tagaste, relates to his Confessions. This, probably his best-known work, was written between 397 and 401. The picture shows him starting school at the elementary school of Tagaste. The teacher walking towards the young Augustine is greeting him by gently caressing his face. Within the family group his mother, St Monica, is highlighted by means of a golden halo which obeys the laws of perspective. In the simultaneous scene on the right the teacher is punishing a pupil while the little Augustine is attentively studying a school slate with Greek letters on it. From the scale of the buildings and figures it can be seen how far the pictorial space extends backwards. In this way Benozzo creates a counterweight to the arrangement of the figures parallel to the picture in the foreground. Particularly characteristic of this cycle is the city view with buildings in the style of the Early Renaissance, including depictions of some that really exist. The inscription tells us that Augustine made considerable advances within a short space of time in the Latin school of Tagaste, and emphasizes the Latin element that dominated his education. |

||

2 St Augustine at the University of Carthage |

||

|

||

St Augustine at the University of Carthage (scene 2, north wall), Apsidal chapel, Sant'Agostino, San Gimignano |

||

| The fresco with St Augustine at the University of Carthage has been severely damaged. St Augustine is kneeling on the right side in front of two seated scholars. Between them, in the background, appear two youthful figures framed by a classical pediment portal. In 371 St Augustine went to the University of Carthage in order to study the liberal arts. These can be subdivided into the trivium of grammar, rhetoric and logic, and the quadrivium of arithmetic, geometry, astronomy and music. In his encyclopaedia work "Satiricon" (ca. 450), Marcianus Capella stated that there were seven liberal arts. In Carthage, Augustine became familiar with Cicero's philosophical treatise "Hortensius'; and this led to his first conversion, when he adhered to Manichaeism. This was a dualistic philosophy founded by the Persian Mani (216-273), which comprised the battle between light and darkness, between good and evil. In the two first pictures, the School of Tagaste and the University of Carthage, the figural scenes appear within a perspectively painted architecture typical of the Early Renaissance. In contrast to Montefalco, the figures and architecture here form a harmonious whole. |

|

|

3 St Augustine Leaving his Mother |

||

|

||

St Augustine Leaving his Mother (scene 3, east wall), 1464-65, fresco, 220 x 230 cm, Apsidal chapel, Sant'Agostino, San Gimignano |

||

| The fresco on the east wall behind the altar was severely damaged and was restored in the 18th century. It depicts St Augustine leaving his Mother. The figure of St Monica, absorbed in prayer, on the left side of the picture is an almost exact quotation of the motif of St Augustine in the previous fresco. St Augustine's mother appears twice in the fresco. On the left she is kneeling in a church interior which is furnished with a Gothic tracery window and a Gothic polyptych. On the right she is sadly supporting her head and blessing her son with her raised hand. | ||

4 St Augustine's Journey to Rome 5 Disembarkation at Ostia |

||

|

||

Disembarkation at Ostia (scene 5, east wall), 1464-65, fresco, 220 x 230 cm, Apsidal chapel, Sant'Agostino, San Gimignano |

||

| St Augustine made his journey to Rome in 383. The following frescoes (scenes 4 and 5) show both this scene and his Disembarkation at Ostia. Augustine left his native country as he was disappointed by the fantastical mythology of the Manichaeists and finally abandoned this philosophy.

In this picture it is particularly clear how Benozzo, in contrast to his earlier fresco cycles, chose a close-up composition for his frescoes, particularly in the lower register. This makes it possible for the figures in the foreground to appear as if on a stage. In contrast to the real events, though, Benozzo moved to scene to a typically Tuscan hilly landscape. |

||

6 St Augustine Teaching in Rome |

||

|

||

St Augustine Teaching in Rome (scene 6, south wall), 1464-65,, fresco, 220 x 230 cm , Apsidal chapel, Sant'Agostino, San Gimignano |

||

| The scene of St Augustine Teaching in Rome shows the saint as an older man and scholar of rhetoric. Compared to Augustine's start at the School of Tagaste, Benozzo gave the scene an appropriate distance from the observer. The arrangement and scale of the figures underline the perspective indicated by the floor tiles. The parallel lines converge on the figure of the saint. The two listeners sitting to the right of him are repeated on the left as almost mirror images, thereby supporting the balance of the spatial composition. The pictorial space opens out towards the teacher. The dog sitting on the floor in the foreground is given a predominantly negative status in the Bible. The Fathers of the Church, in contrast, valued it as a guard and loyal shepherd, and it was interpreted as a symbol of the preacher. | ||

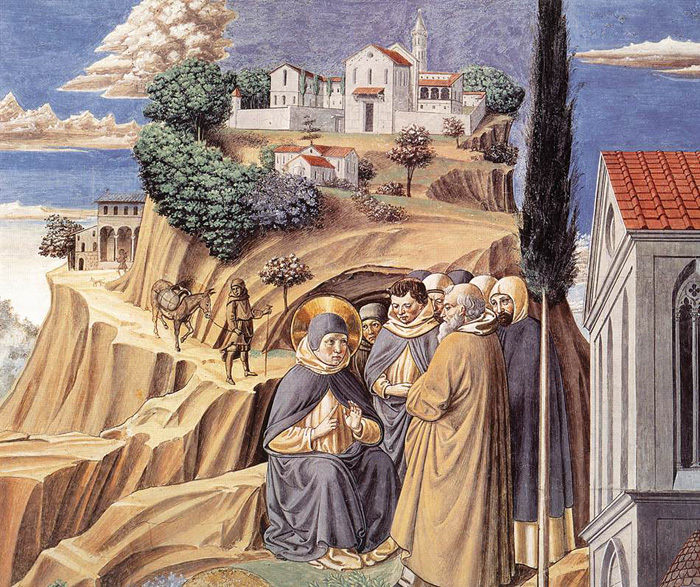

7 St Augustine Departing for Milan |

||

|

||

Benozzo Gozzoli, St Augustine Departing for Milan (scene 7, south wall), 1464-65, fresco, 220 x 230 cm, Apsidal chapel, Sant'Agostino, San Gimignano |

||

| St Augustine had left Rome in the autumn of 384 in order to take up the position of municipal teacher of rhetoric in Milan. St Augustine departing for Milan is depicted by Benozzo in the manner described in the Confessions, as a pilgrimage in search of the true faith. It is thought that the figure on the right edge of the picture is a self portrait of the artist. The gestures and facial expressions clearly express reserve, while at the same time his left hand is pointing at the travelling saint. Above the train of pilgrims two angels are holding an inscription which names the client and artist: ELOQUII SACRI DOCTOR PARISINUS ET ENGENS, GEMINGNACI FAMA DECUSQUE SOLI, HOC PROPRIO SUMPTU DOMINICUS ILLE SACELLUM INSIGNEM IUSSIT PINGERE BENOTIUM. MCVVVLXV - "As a teaching preacher in Paris and as an important [man], the fame and credit to the country of Gimignano, that Dominicus had this holy tabernacle painted at his own expense by the famous Benozzo. 1465." |

||

8 Arrival of St Augustine in Milan |

||

|

||

Arrival of St Augustine in Milan (scene 8, north wall), 1464-65, fresco, 220 x 230 cm, Apsidal chapel, Sant'Agostino, San Gimignano |

||

| The first picture in the second row on the left shows the Arrival of St Augustine in Milan. In front of a columned loggia, which is reminiscent of the Loggia dei Lanzi (between 1376 and 1381) with three bays in Florence, St Augustine appears in several small simultaneous scenes. Here Benozzo makes a more decisive use than he did in Montefalco of the opportunities of emphasizing the scenes in the picture by means of the architecture: in one place, the saint is standing in front of a column, and at another between two columns.

In the Arrival of St Augustine in Milan, Benozzo once again combines three scenes from the legend of St Augustine as simultaneous events. On the first occasion St Augustine appears before the columned loggia and a servant is helping him take off his riding clothes. In the background, the saint is kneeling before a Muslim scholar. In the foreground on the right we can see St Augustine being greeted by St Ambrose. |

||

9 Scenes with St Ambrose |

||

|

||

Scenes with St Ambrose (scene 9, north wall), 1464-65, fresco, 220 x 230 cm, Apsidal chapel, Sant'Agostino, San Gimignano |

||

| The fresco showing the Scenes with St Ambrose depicts St Augustine hearing the bishop preaching in Milan. Here, too, St Augustine is depicted twice: on the left he is talking with the seated St Ambrose. On the right side St Augustine has taken his seat at the edge of the picture before a niche. At this point the fresco is unfortunately severely damaged. The two scenes are clearly separated from each other by the construction of the picture. The preaching of St Ambrose made it possible for St Augustine to overcome the Manichaeist criticism of the Bible by means of allegorical biblical exegesis and Neoplatonic intellectuality. St Ambrose caused Augustine finally to convert to Christianity. |

||

10 St Augustine Reading the Epistle of St Paul |

||

|

||

St Augustine Reading the Epistle of St Paul (scene 10, east wall), 1464-65, fresco, 220 x 230 cm, Apsidal chapel, Sant'Agostino, San Gimignano |

||

| In the following fresco, St Augustine hears a voice in the seclusion of a garden commanding him to "take up the book and read". Accordingly, he takes up the epistle of St Paul to the Romans, and starts reading Romans 13:13 ff., which warns sinners to "put ye on the Lord Jesus Christ, and make not provision for the flesh, to fulfil the lusts thereof." On the right his intellectual friend Alypius is reaching out to him with his hand. Two old friends, on the left side, are keeping their distance from his on account of his change of faith. The phrase coined by St Augustine, "credo ut intelligam, intelligo ut credam" - "I believe that I might understand, and understand that I might believe" - appears to have been visually translated into this picture. | ||

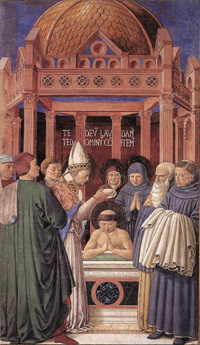

11 Baptism of St Augustine |

||

|

||

Baptism of St Augustine (scene 11, east wall), 1464-65, fresco, 220 x 230 cm, Apsidal chapel, Sant'Agostino, San Gimignano |

||

| St Augustine is seen at the very moment he is baptized, kneeling in prayer before the pillars of a baptistery behind a rectangular basin filled with water, on which the picture's date of origin has been recorded: ADI PRIMO DAPRILE MILLE CCCCLXIIII (1 April 1464). He is surrounded by his followers, including his mother who is standing behind him. The clergyman holding the newly baptized man's clothing is thought to be a portrait of Domenico Strambi, the man who commissioned the cycle.

The Baptism of St Augustine was, according to the "Legenda Aurea" or Golden Legend, carried out at Easter 378 by St Ambrose in Milan with the words "te Deum laudamus" (we praise you as [our] God), to which St Augustine replied "te Dominum confitemur" (we recognize your as [our] Lord). This liturgical hymn of thanksgiving, the "Te Deum", is mentioned in the "Legenda Aurea" as being a song of praise between St Ambrose and St Augustine. In the medieval liturgy, the "Te Deum" was sung as the conclusion of Matins the midnight office, and on ceremonial liturgical occasions. The melody is one of the oldest Gregorian chants. The architecture of the baptistery, with an individual pilaster for each of the figures in the picture, emphasizes the religious dignity of the event. |

||

12 The Parable of the Holy Trinity |

||

|

||

The Parable of the Holy Trinity (scene 12, south wall, detail), 1464-65, fresco, 220 x 230 cm, Apsidal chapel, Sant'Agostino, San Gimignano |

||

| In the next fresco of the cycle, a boy on the left is attempting to use a spoon to transfer all the waters of the ocean into a little hollow. The episode is described in an apocryphal letter of Cyril of Jerusalem, and shows that the client was a particularly good expert on literature concerning St Augustine. In the letter Cyril writes that St Augustine, while thinking about the Trinity, met a small child on the beach who was attempting to ladle out the oceans using a spoon. When St Augustine explained to him how impossible his plan was, the boy replied by telling him that the mystery of the Holy Trinity was also not something that could be comprehended by the human mind. The scene is a parable of the unbridgeable gap between faith and reason. In the middle distance, St Augustine is sitting surrounded by a circle of monks on a bare path leading to a monastery on the top of the mountain. The Visit to the Monks of Mount Pisano is depicted for the first time in this fresco, emphasizing its uniqueness. In the foreground on the right, St Augustine is giving the rule of the order to the hermit monks. He is wearing the dress of Augustinian hermits, a black habit with a pointed hood, leather belt and shoes. There is no historical proof of St Augustine's journey to Tuscany. The event is also not mentioned in the Confessions. However, oral tradition has it that St Augustine stayed in Tuscany after his mother's death. Due to grief at the loss of his mother, he is said to have forgotten to write it down. According to tradition, St Augustine visited the hermit monks of Mount Pisano. This legend was very popular as it suggested that the Augustinian hermits had originated in Tuscany. In fact, St Augustine founded his community in the fourth century in northern Africa. The rule of the Augustinians, dating from 388/389, is the oldest Western monastic rule. In 12 short chapters it lays down the fundamentals of monastic life. The goals of the monastic community are poverty, brotherly love, obedience, prayer, reading the Scriptures, work and apostolic work: a life characterized by seclusion and humility. Not until 1256 did Pope Alexander (1254-1261) found the order of Augustinian hermits by combining several Italian groups of hermits who had been living according to the rule of St Augustine since 1243. |

||

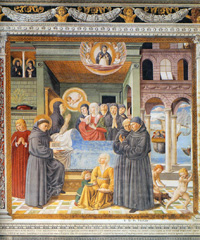

13 Death of St Monica |

||

|

||

Death of St Monica (scene 13, south wall), 1464-65, fresco, 220 x 230 cm, Apsidal chapel, Sant'Agostino, San Gimignano |

||

| The Death of St Monica (387) in Ostia is combined with the departure for Carthage in the last picture of the second row. Here the client, Domenico Strambi, has also allowed himself to be immortalized. He is standing on the right next to the death bed, as we are told by the initials in the frame: F D M Paris, Frater Dominicus Magister Parisinus.

This picture field shows the praying St Monica on her deathbed. Above, St Monica appears in a small glory of angels in which her soul is being carried up to heaven. In the background on the right one can, through an open colonnade, see the departure of St Augustine for Numidia. |

||

14 Blessing of the Faithful at Hippo |

||

|

||

Blessing of the Faithful at Hippo (scene 14, north wall), 1464-65, fresco, width 440 cm, Apsidal chapel, Sant'Agostino, San Gimignano |

||

| The Blessing of the Faithful at Hippo occupies the lunette field on the north wall and is as wide as the two pictures beneath it put together. The badly damaged fresco shows the Blessing of the Faithful at Hippo.

In a perspectively constructed church interior St Augustine is blessing the faithful of Hippo kneeling on the left side. On the severely damaged right side, he can still be recognized by his bishop's miter. The church interior contains numerous references to known works of art from the Early Renaissance. For example, on the door lunette on the left edge of the picture there is a terracotta group in the style of Luca della Robbia. |

||

15 Conversion of the Heretic |

||

| The little lunette field to the left of the window depicts the Conversion of the Heretic and Manichaeist presbyter Fortunatus. Here St Augustine is depicted as a bishop, though he is wearing the habit of the Augustinian hermits beneath his surplice. The event is described in the "Legenda Aurea" and refers to the many conversions made by St Augustine and his successful battle against heresy. | ||

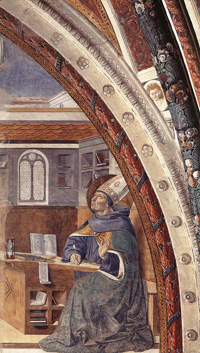

16 St Augustine's Vision of St Jerome |

||

|

||

St Augustine's Vision of St Jerome (scene 16, 1464-65, fresco, Apsidal chapel, Sant'Agostino, San Gimignano |

||

| The lunette field on the right shows St Augustine's Vision of St Jerome with the former depicted as a scholar. This type of depiction was based on late classical pictures of authors and became extremely important in the 15th century. It was used by famous masters such as Botticelli and Domenico Ghirlandaio for their paintings in the Ognissanti monastery in Florence. |  |

|

|

||

Funeral of St Augustine (scene 17, south wall), 1464-65, fresco, width 440 cm, Apsidal chapel, Sant'Agostino, San Gimignano |

||

| The last scene showing the Funeral of St Augustine appears in the lunette field on the south wall. The construction of the picture is clearly reminiscent of the Death of St Francis in Montefalco, but because of the open columned loggia in the background it has a more harmonious composition. As in Montefalco, thedead man's bier is standing in the foreground.

The loggia behind the mourners is a quotation of the Ospedale degli Innocenti (orphanage) which Filippo Brunelleschi started building in Florence in 1419. The orphanage, which is situated in the vicinity of the monastery of San Marco, would certainly have been known by Benozzo, for the innovative columned architecture that the building used soon spread right across Europe. It is all the more astonishing, however, that in this picture pillars instead of columns are supporting the arches, in keeping with a requirement in Leon Battista Alberti's famous treatise "De Re Aedificatoria" (On Architecture), written in 1451. |

||

Frescoes of saints on the pillars |

||

| The two entrance pillars to the chapel round off the fresco paintings with four saints on each side. These eight saints represent an important addition to the life of St Augustine. Their portraits are placed in niches in order to create the impression that they are sculptures. The impression of painted sculptures is contradicted by the garments which extend beyond the painted architecture. On the northern pillar are St Monica, St Sebastian, St Bartolus and St Gimignano. On the southern pillar St Nicholas of Bari, St Fina, St Nicholas of Tolentino and Raphael and Tobias are depicted. The eight saints standing in niches on the fronts and sides of the choir pillars are important elements in the design. The four saints in the lower register, Sebastian, Bartolus, Nicholas of Tolentino and Tobias, are each provided with a story related to their lives. St Monica, the mother of St Augustine, is in contrast to customary iconography holding a book instead of a rosary. This may be a reference to her son's eagerness to study, for he learnt about the Christian faith from his mother. The patron saint of San Gimignano was a local saint, and he is holding a realistic view of the town in his hands. According to legend, he is supposed to have protected it from Attila's attacks while he was bishop of Modena. This prompted the little town, formerly called Silvio, to change its name to Gimignano. St Sebastian, who according to St Ambrose came from Milan, suffered his martyrdom in Rome at the end of the third century. He, one of the 14 auxiliary saints, is holding an arrow and a palm frond, attributes which identify him as a martyr. As an auxiliary saint in time of plague, his worship became increasingly important from the 14th century onwards. In keeping with the other pictures in the lower register, the composition includes a "historia" which relates to the life of the saint. St Bartolus, the patron saint offering protection from infectious diseases, came from the vicinity of San Gimignano and was also depicted here for that reason. He was born in San Gimignano in 1228 and lived as a member of the Third Order of Franciscans in the monastery of San Vito in Pisa. Himself a leper, for 20 years he ran the leper home in Cellole near San Gimignano, where he died in 1300. St Nicholas was the bishop of Myra in Lycia (now in Turkey), which is why he is also known as Nicholas of Myra, and he died in about 350. His relics were stolen from Myra by pirates in 1087 and brought to Bari, which explains the saint's official name. He is holding three golden balls in his hand, which according to the so-called legend of the virgins he gave to three impoverished girls so that they would have a dowry befitting their station and would not be disgraced. St Fina is only depicted in the area around San Gimignano. Though she died in 1253, aged just 15 years, her short life is said to have been filled with miracles. Despite her poverty she was charitable and had a heroic capacity for suffering. Benozzo has depicted the virgin with her characteristic attribute, the roses. The picture type of the archangel Raphael and Tobias first appeared in the 15th century. The event depicts a parable of God's mercy: Tobias, who was sent out on a journey by his blinded father, is being protected and guided by the archangel Raphael. When Tobias washes his feet in a river, he is frightened by a large fish, which he catches and guts on the advice of the angel. The innards prove to be a medicine which he can use to restore his father's sight. St Nicholas of Tolentino, who was not canonized until 1446, was one of the most popular saints of the order of Augustinian hermits, which he entered in 1255. The attribute he is holding is a white lily, a symbol of the purity of his mind. |

||

|

||

|

||

View of the vaults, 1464-65, fresco, Apsidal chapel, Sant'Agostino, San Gimignano |

||

| The vaulting shows the four Evangelistson concentrically painted clouds. The four Evangelists symbolize the kingdom of God, and they are depicted on the four fields of the groin vault in the process of reading or writing down their works: St Mark is shown with the lion, St Matthew with the angel, St Luke with the ox and St John with the eagle. The concentrically painted clouds create the impression of a circular vault. | ||

|

||

[1] Benozzo di Lese, surnamed Gozzoli after his death, was a favorite pupil of Fra Angelico. Vasari’s somewhat amusing commentary on him is that he was "of great invention, very fertile in animals, in perspective, in landscapes, and in ornament. He produced so much during his life that it is plain he cared for no other occupation; and although compared to others who surpassed him in drawing he was not very excellent, yet the amount of work he did placed him ahead of all his contemporaries, because, in the multitude of his works, some turned out well." |

On the right edge of the fresco St Augustine Departing for Milan, the painter has immortalized himself in a light red garment |

|

The progress shown in this picture in the naturalistic movement, in the direction pointed out by Fra Filippo, is most remarkable. The landscape is still purely subjective and devoid of the qualities of outdoor work; but there appears a most noteworthy distinction of specific character in the trees, the evergreen and deciduous pines and cypresses especially being recalled with landscape feeling, and the foreground plants being done in the sentiment of a lover of nature. Though recorded as the pupil of Fra Angelico,—and so far as the processes of his art may be concerned he may have been so, as Fra Angelico was an admirable master of the fresco and tempera processes,—in the spirit of his work, his intellectual and artistic tendencies, Benozzo is the son and heir of Fra Filippo, and his successor in the line which Masaccio had pointed out and the Frate had walked in. There is not only the recognition of the individual type in all his personages, but there is the distinct and undeniable indication of the use of the model through drawings made for all the figures in his compositions. There is no advance towards realism, but a complete abandonment of the visionary and ecstatic type so marked in Fra Angelico. We come down to plain flesh and blood, and every personage in this long procession has posed for the drawing made for it. It is the most extraordinary agglomeration of pose-plastique in all the range of the Renaissance; and in the densest part of the crowd, and no matter what his action, every actor turns his face more or less so as to be seen and recognized by those who know him. There is no mistaking that for every one of these heads and all the principal figures careful drawings must have been made from life. Every figure says, "I am being drawn by Benozzo for his great picture of the Magi." It is such a collection of unquestionable portraits as I do not know elsewhere in the world. Hic tumulus est Benotii Florentini quif proxime has pinxit historias From Wikisource, Century Magazine by W. J. Stillman, Volume 39, Issue 1 (November, 1889), Old Italian Masters. Benozzo Gozzoli |

||

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Benozzo Gozzoli | ||

Holiday accomodation in Tuscany | Podere Santa Pia | Artist and writer's residency

|

||||

Podere Santa Pia |

Podere Santa Pia, garden view, April |

View from terrace with a stunning view over the Maremma and Montecristo |

||

|

|

|

||

San Gimignano |

Abbazia di Monte Oliveto Maggiore |

San Marco, Firenze |

||

San Gimignano |

||||

San Gimignano is situated in the Val d'Elsa, 56 km south of Florence. Its walls and fortified houses form an unforgettable skyline, in the heart of the Etruscan landscape. |

|

|||

Palazzo Medici Riccardi, Florence |

Piazza della Santissima Annunziata in Florence |

Florence, Duomo |

||