| |

|

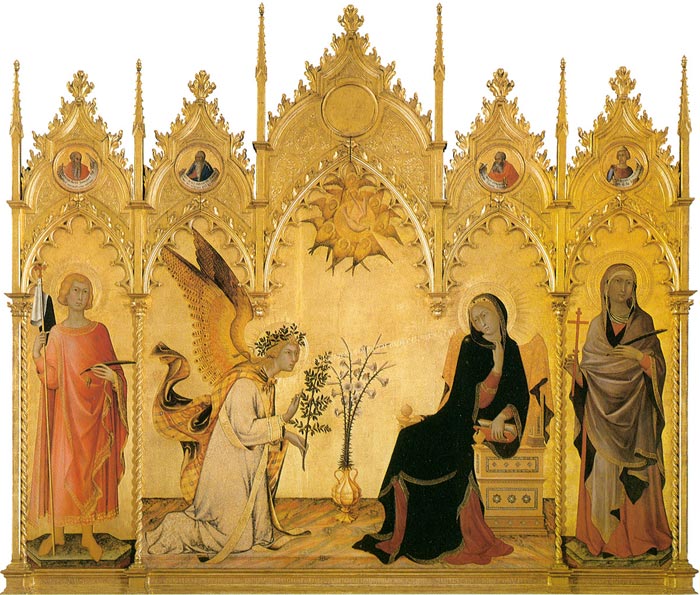

The Annunciation with St. Margaret and St. Ansanus is a painting by the Italian Gothic artists Simone Martini and Lippo Memmi, now housed in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, Italy. It is a wooden triptych painted in tempera and gold, with a central panel having double size. Considered Martini's masterwork and one of the most outstanding works of Gothic painting,[1] the work was originally painted for a side altar in the Siena Cathedral.

History

The painting originally decorated the altar of St. Ansanus in the Cathedral of Siena, and had been commissioned as part of a cycle of four altarpieces dedicated to the city's patrons saints (St. Ansanus, St. Sabinus of Spoleto, St. Crescentius and St. Victor) during 1330-1350. These included the Presentation at the Temple by Ambrogio Lorenzetti (altar of St. Crescentius, 1342), the Nativity of the Virgin by Pietro Lorenzetti (1342, Altar of St. Sabinus), and a Nativity, now disassembled, attributed to Bartolomeo Bulgarini from 1351 (altar of St. Victor). All the paintings should represent stories of the Life of the Madonna, and were crowned by Duccio di Buoninsegna's Maestà. The artists' use of expensive lacquer, extensive gold leafing and the difficult to obtain lapis lazuli in the painting demonstrates the communal prestige of the commission.

The date of the painting is specified in a fragment of the original frame, now embedded in the 19th-century renovation. It lists the name of Simone Martini and his brother-in-law Lippo Memmi (SYMON MARTINI ET LIPPVS MEMMI DE SENIS ME PINXERVNT ANNO DOMINI MCCCXXXIII), although it is unknown which parts they executed. A hypothesis is that Martini painted the central panel, while Memmi was responsible of the side saints and the tondoes with prophets in the upper part.[1]

The work, in both size and style, has no similarities with any other contemporary painting in Italy. It can be compared instead to French illuminated manuscripts of that time, as well as to paintings from Germany or England. His "northern European" style granted Martini a call from the papal court in Avignon, where there were Italian but no Florentine painters, as the Giottesque classical manner was met with little interest by the Gothic culture of the area.

The painting remained in the cathedral until 1799, when Grand Duke Peter Leopold had it moved to Florence in exchange of two canvasses by Luca Giordano. The original frame, carved by Paolo di Camporegio and gilt by Memmi, was renovated in 1420 and replaced by a modern one in the 19th century.

Description

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

The work is composed of a large central panel depicting the Annunciation, and two side panels with St. Ansanus (left), and female saint, generarally identified with St. Maxima[2] or St. Margaret, in the right, and four tondoes in the cusps: Jeremiah, Ezechiel, Isiah and Daniel.

The Annunciation shows the archangel Gabriel entering the house of the Virgin Mary to communicate her that she will soon bear the child Jesus, whose name means the "Savior." Gabriel holds an olive branch in his hand, a traditional symbol of peace, while pointing at the Holy Ghost's dove with the other. The dove is descending from heaven, from the center of the mandorla of eight angels above, about to enter the Virgin's right ear. In fact, along the path of the dove, viewers see Gabriel's utterance, "Hail, thou that art highly favored, the Lord is with thee: blessed art thou among women." The angel's mantle shows a detailed "tartar cloth" pattern and fine gilt feathers.

The Virgin, sitting on a throne, is portrayed at the moment that she is startled out of her reading, reacting with a graceful and composed reluctance, looking with surprise at the celestial messenger. Also, her dress has an arabesque-like pattern.

At the sides, the two patrons saints of the cathedral are separated by the central scene by two decorate twisting columns. The background, completely gilt, has a vase of lilies, an allegory of purity often associated to the Virgin Mary.

The use of a Gothic line, plus such realistic elements as the book, the vase, the throne, the pavement in perspective, the realistic action of the two figures and their subtle nuances of character are a substantial detachment from the bi-dimensionality typical of Byzantine art.

|

|

Simone Martini e Lippo Memmi, Annunciazione tra i santi Ansano e Massima (particolare della Vergine), 1333, Galleria degli Uffizi, Firenze

|

The Annunciation is considered an absolute masterpiece and one of the greatest examples of Sienese Gothic painting, characterized by the wonderful elegance of both line and color.

The Archangel has just touched ground in front of the Virgin as shown by his unfold wings and his swirling mantle. The scene seems a theatrical performance, as stressed by the comic strip like sentence in the middle of the composition with the greeting of the angel. The Virgin is portrayed almost surprised and frightened by the sudden appearance. Her movement, so prim and elegant, adds a certain effect of sophistication to the work.

The altarpiece has a gold background, so bound to tradition, and still very much in demand for the depictions of sacred stories. The artists adhered therefore to what customers required, but they used to insert some details that could make the composition more realistic.

For this purpose Simone Martini included some delightful details in the main scene as the marble floor, the mantle of the archangel, the pot of lilies, the half-closed book of Mary and her throne, all of which suggest a real space, otherwise penalized by the gold background.

The garments of the four characters take shape thanks to the snaky and decorative line typical of Sienese school.

The painting is then fully Sienese for the beauty and the gentleness of lines and colors, just in opposition to Florentine style, more related to the volume and the shape.[3]

|

|

Simone Martini e Lippo Memmi, Annunciazione tra i santi Ansano e Massima (particolare, l'arcangelo Gabriele), 1333, Galleria degli Uffizi, Firenze

Detail of the Annunciation Angel

|

|

Simone Martini e Lippo Memmi, Annunciazione tra i santi Ansano e Massima (particolare, l'arcangelo Gabriele appare alla Vergine), 1333, Gallerie degli Uffizi, Firenze [1]

|

A complete novelty in the iconography of the Annunciation is the manifestly fearful attitude of the Virgin.

The first to faithfully reproduce Simone's invention was Lippo Memmi himself, in the Annunciation of the Collegiate Church of San Gimignano. The same attitude of the Martinian Madonna is then found in a masterpiece by Ambrogio Lorenzetti, the Annunciation of the Hermitage of Montesiepi, where the Virgin is so frightened that she clings to a column, and again in the Annunciation painted by Andrea di Bartolo in the polyptych of the Pieve di Buonconvento of 1397, or in the Annunciation of Taddeo di Bartolo (Siena, Pinacoteca Nazionale) [4] .

We also see this attitude of the Virgin in 15th century with the ‘Maestro dell'Osservanza’ (in the Pala dell'Osservanza), or in the Annunciations with the Saints John the Baptist and Bernardinus painted by Giovanni di Pietro and Matteo di Giovanni, or, for example, in the 16th century with Domenico Beccafumi's Annunciation in the church of San Martino in Foro (Sarteano).

|

| |

|

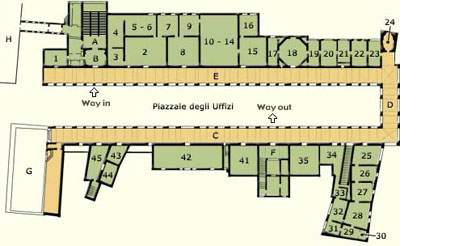

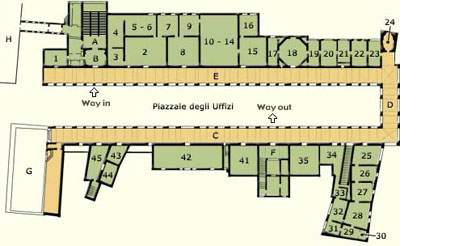

Gallerie degli Uffizi

Postal & visiting address: Piazzale degli Uffizi, I-50122 Florence (Firenze)

Web | www.uffizi.firenze.it

Museum Hours

Open Tuesday through Sunday, 8:15am – 6:50pm

Closed: every Monday, January 1, May 1, December 25

Room Plan

|

|

|

| |

|

|

The Annunciation by Simone Martini and Lippo Memmi is one of the greatest examples of Sienese Gothic paintings and is placed at the Uffizi.

The Annunciation was made for the Sant’Ansano altar in the Duomo of Siena. In 1979, it was moved to the Uffizi. It is located in the International Gothic Room and is an important example of this period of art history.

S E C O N D F L O O R

Room 1 - Archaeological room

Room 2 - Giotto and 13th Century

Room 3 - Senese Painting 14th Century

Room 4 - Florentine Painting 14th Century

Room 5/6 - International Gothic

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

The Annunciation | Art in Tuscany

Art in Tuscany | Giorgio Vasari's Lives of the Artists | Simone Martini (1285-1344) and Lippo Memmi (d. 1357)

[1] The earliest evidence of Simone's activity is the Maestà fresco in the Palazzo Pubblico (Town Hall) in Siena, signed and dated 1315 (restored and perhaps revised by Simone's himself in 1321). The relationship between Simone's fresco and Duccio di Buoninsegna's Maestà altarpiece of 1311 for the Cathedral of Siena, in the theme of the Madonna in Majesty and in the figure types, suggests that Simone may have received his training in the shop of that earlier Sienese master. If Giorgio Vasari's statement that Simone died at the age of 60 is correct, then the painter was born about 1284 and the Maestà is a mature work by a man of 30, for whom there is no trace of formative years.

The divergence from Duccio's primarily Italo-Byzantine form and expression indicates that Simone's art was rooted in the French Gothic tradition, although there is still no answer to the question of whether he actually worked in France in his earlier years. In the courtly treatment of the subject, the emphasis on richly decorative detail, and the naturalness of space and scale, Simone's fresco announces a new Sienese style. The Virgin's specific role as protector of Siena is conveyed by the location of the fresco in the Council Room of the Town Hall, by a moralizing inscription on justice and oppression, and by the presence of the patron saints of the town.

About 1317 King Robert of Anjou called Simone to Naples and knighted the painter during his stay. The French accent in Simone's art was welcome at the Angevin court. St. Louis of Toulouse Crowning Robert of Anjou (Naples) depicts the saint, canonized in 1317, receiving the heavenly crown and bestowing on his brother the secular crown of the Angevins, thereby renouncing his right to the throne. The altarpiece thus served as both votive icon and testimony to the right of kingship. Simone reveals in this work his consummate skill in the use of the tempera medium and ornamented gold leaf. A series of small scenes (predella) beneath the main panel, depicting episodes from the life of St. Louis, heralds the painter's subsequent works in the varieties of spatial construction and the dramatic force of figure groupings, facial expressions, and gestures. The Renaissance preoccupation of a century later with methods of space depiction had its origins in such early Sienese works.

Following the sojourn in Naples, Simone worked in Pisa (Madonna and Saints, 1319) and Orvieto (Madonna and Saints, 1320). There are no documents or works to affirm Vasari's mention of Simone's activity in Florence, nor is there certainty as to the period of his stay in Assisi, where he frescoed the Chapel of St. Martin in the Lower Church of S. Francesco. These frescoes, along with the fresco Condottiere Guidoriccio da Fogliano (1328) in the Town Hall in Siena, demonstrate Simone's superb talent as a mural decorator and as a recorder of the world of Gothic chivalry and elegance.

In the St. Martin frescoes the entire range of the artist's vision and method unfolds: the sophisticated rendering of interior space and details of architectural setting; a rich interplay of linear rhythms, subtly variegated and luminous colors, and elaborately ornamented costumes and trappings; the close observation of facial expression and a clear division of the personages of a narrative into a social hierarchy through the differentiation of types. The fresco of Guidoriccio faces Simone's earlier Maestà so that in the same official room the religious and secular protectors of the city are confronted. The condottiere had liberated the Tuscan fortress-towns of Montemassi and Sassoforte in 1328. He rides his handsomely bedecked horse proudly in the foreground, both master and steed displaying the armorial device of diamond and vine. At the crest of the barren landscape the besieged towns rise in stark silhouette against the deep-blue background, while the general's encampment holds the far-right hill and valley. This fresco stands as the first in a series of equestrian portraits of heroes in Italian medieval and Renaissance art.

In contrast to the concern for time and place in the frescoes, the Annunciation altarpiece, painted in 1333 for the Cathedral of Siena (now in Florence), emits an atmosphere of sublime unreality. The inscription on the panel records that Lippo Memmi, whose sister Simone had married in 1324, collaborated on the altarpiece. In its elegance of line and rhythm, the exquisitely rendered details of costume, setting, and flower symbols, and the fragile sentiment of the participants in the sacred event, the Annunciationis a supreme masterpiece in the history of lyrical art.

Simone spent his last years at the papal court in Avignon, where he arrived in 1340 accompanied by his brother and collaborator, Donato. They came to Avignon as artists and as official representatives of the Church in Siena. Only one signed and dated work is known from this period in France, the Holy Family (1342; Liverpool). Frescoes in the Cathedral are in a ruined state. A group of four small panels with scenes of the Passion and an Annunciation diptych (now in various museums) project a fervent emotionalism and dramatic tension matched only by the late sculpture of Giovanni Pisano. At Avignon, Simone and the poet-humanist Petrarch formed a close friendship. The painter executed a frontispiece for Petrarch's copy of Commentaries on Virgil (now in Milan), and the poet records in one of his sonnets that Simone painted a portrait, now lost, of his beloved Laura.

Subsequent generations of lesser Sienese painters of the 14th century relied heavily on Simone's model, but a more crucial inheritance is found in that late Gothic mode of European art about 1400 - the International Style. It was Simone Martini who brought Sienese painting into the mainstream of European art.

Further Reading

Giovanni Paccagnini, Simone Martini (1955; trans. 1957), is the most complete and dependable monograph on Martini's work. John White, Art and Architecture in Italy, 1250-1400 (1966), is a masterful survey of late medieval Italian art with penetrating critical essays on individual artists. Evelyn Sandberg Vavalà's two works, Uffizi Studies (1948) and Sienese Studies (1953), provide a history of Florentine and Sienese painting based on a close formal analysis of paintings in the principal galleries of the two cities. An old but still useful study is Ferdinand Schevill, Siena: The History of a Mediaeval Commune (1909).

["Simone Martini." Biographies. Answers Corporation, 2006. Answers.com 25 Nov. 2010. ]

[2] Simone Martini must undoubtedly have been influenced by the proto-Humanist cultural world of Petrarch, and we can see clearly how the manuscript illumination of Petrarch's Virgil in the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan, with its classical and naturalistic overtones (sophisticated gestures, white cloth drapery, the delicate figures of the shepherd and the peasant), anticipates the typical style of early 15th-century French manuscript illumination.

The altarpiece known as Passion Polyptych (or Orsini Polyptych), with panels now in a number of European museums (Angel of the Annunciation and Virgin of Annunciation, as well as Crucifixion and Deposition in Antwerp, the Road to Calvary in Paris and the Entombment in Berlin) is signed "Pinxit Symon "on the two panels of the Crucifixion and the Deposition. It presents several problems, both in terms of stylistic analysis and dating. Some scholars, stressing the fact that it is so different stylistically from all the other works of Simone's Avignon period (nervous lines and expressions), think that it may have been painted earlier and then transported to France; others believe that it may be a late work, commissioned by Napoleone Orsini, who died in the Curia in Avignon in 1342. Orsini's coat-of-arms appears in the background of the Road to Calvary. The polyptych was probably transferred to the charterhouse of Champmol, near Dijon, in the late 14th century.

[3] Source: Annunciation by Simone Martini and Lippo Memmi at Uffizi Gallery | www.uffizi.org

The original frame, carved by Paolo di Camporegio and gilt by Memmi, was renovated in 1420 and replaced by a modern frame in the 19th century.

[4] Simone Martini et Lippo Memmi, « Annunciazione con due Santi. Pala di Sant’Ansano » | Guide artistique de la Province de Sienne | www.provincedesienne.com

|

| |

|

|

|

|