|

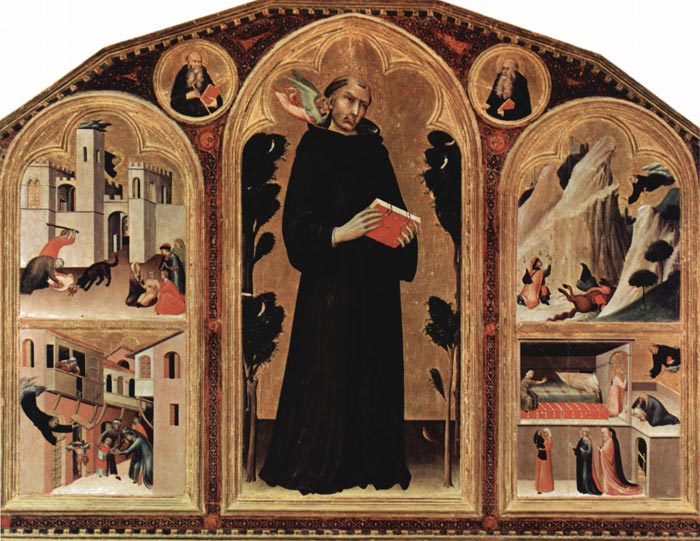

| Blessed Agostino Novello Altarpiece, 1324, tempera on wood, 198 x 257 cm, Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena |

Simone Martini | The Blessed Agostino Novello Altarpiece |

After having spent several years in Assisi, Pisa and Orvieto, only occasionally returning to Siena for very brief periods during which he worked in the Palazzo Pubblico (on one occasion to retouch the Maestà, on another to paint some works that are no longer extant), Simone Martini actually returned to Siena on a stable basis. This appears to have been a rather calm period of his life and it was at this time that he married Giovanna Memmi: perhaps feeling tired after his travels, working for so many different patrons in different places, Simone decided to settle in his home town. [1] It was sometime around 1325 and Simone was a well established painter, at the height of his artistic maturity. His experiences working for the House of Anjou and the Franciscans, in international environments where political interests frequently took the place of religious spirit and where art became an effective means of visualizing and promoting temporal power, had made Simone much more a man of the world: he had set off from Siena as a talented but simple Sienese painter, and he returned as a famous artist, selfconfident and experienced. Back in Siena, Simone worked for the Government of the Nine adding more and more splendid works to the Palazzo Pubblico, year after year; most of these paintings have not survived and we only know about them from the payments recorded in the Biccherna ledgers. It was during this second Sienese period that Simone painted some of his most famous paintings, such as the Blessed Agostino Novello Altarpiece, the celebrated fresco of Guidoriccio da Fogliano and the Annunciation now in the Uffizi, the only one that is actually signed and dated.[1] |

|

|

||||

|

||||

Podere Santa Pia, an ancient country estate, faces the gentle hills of Maremma Region. Although Santa Pia is off the beaten track it is the ideal choice for those seeking a peaceful, uncontaminated environment. |

||||

Podere Santa Pia |

Podere Santa Pia, view from the garden on the valley below |

Florence, Duomo |

||

Tombolo di Feniglia |

Crete Senesi, Asciano |

L'eremo di Montesiepi (the Hermitage of Montesiepi) |

||

|

||||

| Arezzo | Sansepolcro |

Sunsets in Tuscany |

||

|

||||

| Podere Santa Pia and the breathtaking view on the Tyrrhenian coast | ||||