Masaccio | The Pisa Altarpiece (1426) |

Masaccio was the most revolutionary painter of the Early Renaissance. 'The Virgin and Child' in the National Gallery is the central fragment of one of his most important works, a polyptych made at the age of 25 for the church of the Carmine in Pisa.

|

Conjectural arrangement of the surviving panels [2]

|

The painting is the central panel of a large, 19 pieces winged altar executed for a chapel of the Carmelite Church in Pisa. The panels of the altarpiece are in various museums. The painting has been cut down at the base, and has lost its original frame, although the arch at the top, firmly locating the throne behind it, is Masaccio's. The silver-leaf backing of the Virgin's red robe has tarnished, the red itself has darkened, and the paint surface is abraded and disfigured, revealing the green undermodelling of the Virgin's face. The original effect would have been much more decorative. Yet decoration could never have been Masaccio's main interest. The Virgin, as voluminous as a Roman statue, sits on a massive throne incorporating the three orders of columns of Roman architecture. The wavy pattern at the base is copied from Roman sarcophagi. The Child himself, naked and plump like a sculpted Roman putto, wears an elliptical halo on his head; its foreshortening defines his position on his mother's lap. The altarpiece was confined within an old-fashioned format: a richly carved, conservative Gothic retable, with little images of saints set into the frame, one on top of the other. Vasari gave a detailed description of the work which was the basis for art critics for the attempt at reconstruction and for the recovery and identification of the work which was dismantled and dispersed in the 18th century. Only eleven pieces have so far come to light and they are not sufficient to enable a reliable reconstruction of the whole work.

|

|

Madonna with Child and Angels (detail), 1426, egg tempera on poplar, 136 x 73 cm, National Gallery, London |

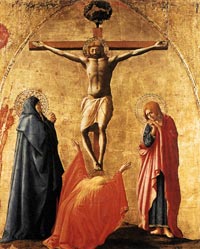

| This is the centre of an altarpiece commissioned by a Pisan notary, Ser Giuliano degli Scarsi, for the chapel of Saint Julian in Santa Maria del Carmine, Pisa. The grapes the Child eats refer to the blood shed on the cross and the wine of the Last Supper. The surface is disfigured by losses and old retouchings and was originally more decorative: the Virgin's dress was a translucent red over silver leaf, which has now dulled. The altarpiece is likely to have been designed as a polyptych. The rediscovery of this panel by BernardBerenson in an English private collection in 1907 was the culmination of a campaign of research that had occupied Masaccio scholars for decades. The format of this painting is unusually tall and narrow for the central composition of a polyptych of this date. [0] Masaccio was an innovative artist, who influenced the course of the Renaissance in Italy. This altarpiece shows an early use of single-point linear perspective. Elements of the painting meet at a central vanishing-point and are foreshortened to accommodate the viewpoint of the spectator looking up. The figure of the Child is three-dimensional, emphasised by his elliptical halo. Masaccio may been influenced by the sculptor Donatello who is known to have collected payments for the altarpiece on Masaccio's behalf. The painting contains six figures: the Madonna and Child and four angels. The Madonna is the centre figure and is larger than any of the others to signify her importance. Christ sits on her knees, eating grapes offered to him by his mother. Although he is an exceedingly babyish baby (in comparison to the babies of Masaccio's immediate predecessors, like Lorenzo Monaco or Gentile da Fabriano), the grapes are a symbol of his blood which indicates Christ's awareness of his eventual death. The infant Christ is noticeably plump and childish except for his glance, which is profoundly reflective. His mother offers him the eucharistic grapes, fully cognizant of their portent. The child eats them unhesitatingly. His halo is oval in shape - a circle foreshortened in space. This rationalistic invention by Masaccio was first prominently used in the Brancacci Chapel.[3] The Madonna looks sorrowfully at her child, as she also realises his fate. Art in Tuscany | Masaccio, Madonna and Child with Angels On February 19th 1426 Masaccio agreed to paint an altarpiece for a chapel in the church of the Carmine in Pisa for the sum of 80 florins. On December 26th of that year the work must have been already completed since payment for it is recorded on this date. Vasari gave a detailed description of the work which was the basis for art critics for the attempt at reconstruction and for the recovery and identification of the work which was dismantled and dispersed in the 18th century. Only eleven pieces have so far come to light and they are not sufficient to enable a reliable reconstruction of the whole work. The Crucifixion is one of the eleven panels (one of the top panels) connected with the Pisa Polyptych. As in the main panel, the Gothic arch determines the pictorial frame, the upward stress of which Masaccio modifies in his composition. To counter the vertical trust imposed by the arch, Masaccio creates a strong horizontal effect with the rather exaggerated extension of the arms of Christ on the cross. Although Masaccio still uses the gilt background for his representation, the atmospheric effects remain hauntingly convincing. |

||||

|

||||

Masaccio, Polyptych of Santa Maria del Carmine in Pisa, Crucifixion, Galleria Nazionale di Capodimonte. |

Piero della Francesca, Polyptych of Misericordia: Crucifixion, tempera and oil on panel, Sansepolcro, Museo Civico |

|||

This subject had presented difficulties for artists because St Peter, to avoid irreverent comparison with Christ, had insisted on being crucified upside down. Masaccio meets the problem by underscoring it, the diagonals of Peter's legs are repeated in the shapes of the two pylons, which are based on the ancient Roman Pyramid of Gaius Cestius. Between the pyramids, the cross is locked into the composition. Within the small remaining space the executioners loom toward us with tremendous force as they hammer in the nails. Peter's halo, upside down, is shown in perfect foreshortening. |

||||

This painting is the central predella panel of the Pisa Altarpiece, directly beneath the enthroned Madonna and Child. Compared to Gentile da Fabriano's painting of the same subject done in Florence just a few years before, Masaccio's treatment is entirely new. Besides offering lifelike portraits of the patron and his nephew in contemporary dress at the middle right, he has given the entire scene a convincing atmosphere which surrounds the figures and the landscape. In the distance, the atmosphere breaks down the clarity of the forms resulting in an effect which is referred to as aerial perspective. |

||||

The two scenes represented on this panel are St Julian Slaying His Parents, and St Nicholas saving Three Sisters from Prostitution.

|

Predella panel from the Pisa Altar, 1426, Staatliche Museen, Berlin |

|||

|

||||

Masaccio, Beheading of St John the Baptist, (detail), 1426, Berlin, Staatliche Museen

|

||||

[John T. Spike, Masaccio, 1996, Abbeville Press Inc, pp. 142.] Jill Dunkerton and Dillian Gordon, The Pisa Altarpiece, in Carl Brandon Strehlke, ed.The Panel Paintings of Masolino and Masaccio: The Role of Technique, Milan, 2002, 91-93.

|

||||

This page uses material from the Wikipedia articles Masaccio and Madonna and Child, published under the GNU Free Documentation License. |

||||

|

||||

Podere Santa Pia |

Podere Santa Pia, garden view, April |

View from Podere Santa Pia

on the coast and Corsica |

||

|

||||

Santa Maria Novella a Firenze |

Castello Banfi |

Santa Maria del Carmine, Firenze |

||

|

||||

Wood burning pizza oven in Podere Santa Pia |

Perugia

|

Montalcino |

||

|

||||

| Podere Santa Poa offers its guests a breathtaking view over the Maremma hills and the Tyrrhenian sea and and Montecristo | ||||