|

|

Brancacci Chapel, Church of Santa Maria del Carmine in Firenze |

|

Masaccio | Brancacci Chapel in Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence |

The Cappella Brancacci is a small chapel reached through the cloisters of the Santa Maria del Carmine Church. Most of the church was destroyed in a fire in 1771. It is considered a miracle that the Brancacci and Corsini Chapels survived the intense fire that destroyed everything else in less than 4 hours. The Church belongs to the Carmelite order, and like San Lorenzo, offers an unfinished façade. Masaccio was the first great painter of the Italian Renaissance, whose innovations in the use of scientific perspective inaugurated the modern era in painting. [1] |

| The Brancacci Chapel or Cappella dei Brancacci is a chapel in the Church of Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence. It is sometimes called the Sistine Chapel of the early Renaissance for its painting cycle, among the most famous and influential of the period. Construction of the chapel was commissioned by Pietro Brancacci and begun in 1386. Little remains of the mediaeval building, not only because of the extensive 16th-century alterations but also because of a disastrous fire which gutted the church in 1771. What we see today is in large part the result of the late-baroque rebuilding carried out after the fire by Giuseppe Ruggieri. The fire did not however affect the old sacristy, which still has its chapel with Scenes from the life of St Cecilia attributed to Lippo d’Andrea (c. 1400), the Brancacci Chapel in the right transept, or the Corsini Chapel in the left.

|

|

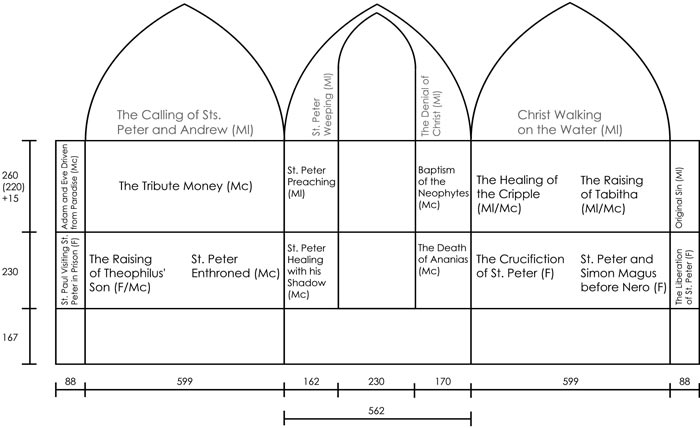

| The frescoes in the upper register are: Adam and Eve in the Earthly Paradise, and Original Sin by Masolino, and the Expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Earthly Paradise with the Tribute Money and the Baptism of the neophytes by Masaccio; also by Masolino are the Preaching of St Peter with the Healing of the lame man and the raising of Tabitha. In the lower register, Masaccio painted the two scenes on the end wall, St Peter curing the sick with his shadow and the Distribution of goods, with the death ot Ananias. |

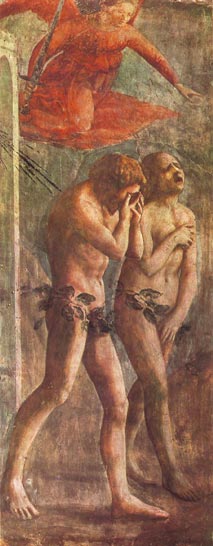

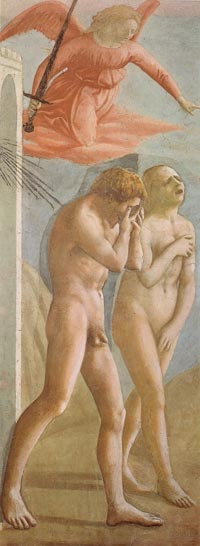

The Expulsion from the Garden of Eden |

||

|

||

Masaccio, The Expulsion Of Adam and Eve from Eden, Brancacci Chapel, Church of Santa Maria del Carmine in Firenze |

||

Masaccio's Expulsion from the Garden of Eden is the first fresco on the upper part of the chapel, on the left wall, just at the left of the Tribute Money. It is famous for its vivid energy and unprecedented emotional realism. It depicts the expulsion from the garden of Adam and Eve, from the biblical Book of Genesis chapter 3, albeit with a few differences from the canonical account. It contrasts dramatically with Masolino's delicate and decorative image of Adam and Eve before the fall, painted on the opposite wall. |

||

|

|

|

|

The fresco was cut at the top during the 18th century architectural alterations. This is one of the frescoes in the chapel which has suffered the greatest damage, for the blue of the sky has been lost. The fig leaves were added three centuries after the original fresco was painted, probably at the request of Cosimo III de' Medici in the late 17th century, who saw nudity as “disgusting”. During restoration in the 1980s the leaves were removed along with centuries of grime to restore the fresco to its original condition. Art in Tuscany | Masaccio | Brancacci Chapel in Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence |

||

|

||

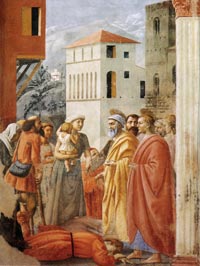

Masaccio, The Tribute Money, fresco in the Brancacci Chapel in Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence |

||

The episode depicts the arrival in Capernaum of Jesus and the Apostles, based on the account given in Matthew's Gospel. Masaccio has included the three different moments of the story in the same scene: the tax collector's request, with Jesus's immediate response indicating to Peter how to find the money necessary, is illustrated in the centre; Peter catching the fish in Lake Genezaret and extracting the coin is shown to the left; and, to the right, Peter hands the tribute money to the tax collector in front of his house. This episode, stressing the legitimacy of the tax collector's request, has been interpreted as a reference to the lively controversy in Florence at the time on the proposed tax reform; the controversy was finally settled in 1427 with the institution of an official tax register, which allowed a much fairer system of taxation in the city. There are other references and allusions which have been pointed out by scholars.

|

||

|

||

|

Masaccio, The Tribute Money, fresco in the Brancacci Chapel in Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence |

||

The Distribution of Alms and the Death of Ananias |

||

|

||

The Distribution of Alms and the Death of Ananias, Cappella Brancacci, Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence |

||

The episode The Distribution of Alms and the Death of Ananias is taken from the account in the Acts of the Apostles (4: 32-37 and 5:1-11) : "For as many as were possessors of lands or houses sold them, and brought the prices of the things that were sold, and laid them down at the apostles' feet: and distribution was made unto every man according as he had need....But a certain man named Ananias, with Sapphira his wife, sold a possession, and kept back part of the price, his wife also being privy to it, and brought a certain part, and laid it at the apostles' feet. But Peter said, Ananias, why hath Satan filled thine heart to lie to the Holy Ghost, and to keep back part of the price of the land?. . . why hast thou conceived this thing in thine heart? thou hast not lied unto men, but unto God. And Ananias hearing these words fell down, and gave up the ghost." Masaccio brings together the two moments of the story: Peter distributing the donations that have been presented to the Apostles and the death of Ananias, whose body lies on the ground at his feet. The scene takes place in a setting of great solemnity, and the classical composition is constructed around opposing groups of characters. No scholar has ever doubted that the entire scene is by Masaccio, except for minor cases of details having been retouched, such as certain parts of Ananias's body, small sections to the far left where the colour had come off, and even tiny areas on St Peter himself.

|

||

The recent restoration has provided us with interesting information: for example, we can now see that there are several details that are not the work of Masaccio, such as St John's pink cloak and his tunic, and Ananias's hands. It was suggested that all these elements were repainted by Filippino Lippi, all in one day's work, over Masaccio's original fresco. As well as a reference to salvation through the faith, this fresco has also been interpretedas another statement in favour of the institution of the Catasto, for the scene describes both a new measure guaranteeing greater equality among the population and the divine punishment of those who make false declarations. And it has also been suggested that the fresco contains a reference to the family who commissioned the cycle: the man kneeling behind St Peter's arm has been identified as Cardinal Rinaldo Brancacci, or alternatively as Cardinal Tommaso Brancacci. Due to the interference of the altar and marble balustrade set up in the l8th century, no scholar had been able to notice that the two episodes on the end wall are ideally part of a single composition, although they are intended to be seen from different viewpoints: the Distribution of Alms along the corner axis of the building in the centre, from a position to the right of the entrance, while the scene of Peter Healing the Sick with his Shadow is intended to be viewed from the middle of the chapel, from fairly close up. The connection between the two scenes is further emphasized by the fact that on the window side neither has pilaster strips framing the outer edge. The original two-light window, so narrow and tall, did not really interrupt the continuity of the wall space: on the contrary, its concave surface provided an ideal connection with the space outside, not as a further background element, but rather as a real source of light, enhancing the three-dimensional features of the characters and contributing to the contrast between light and dark areas. |

||

|

||

St Peter Healing the Sick with his Shadow |

||

|

||

|

Masaccio, St Peter Healing the Sick with his Shadow, (detail) 1426-27, fresco, 230 x 162 cm, Cappella Brancacci, Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence |

||

In the Acts of the Apostles (5: 12-14) the episode St Peter Healing the Sick with his Shadow is recounted immediately after the story of Ananias.

Scholars have never doubted that this scene is entirely by Masaccio. Starting with Vasari (1568), who used the man with the hood as the portrait of Masolino he put on the frontispiece of his biography of the artist, all later scholars have tried to identify the contemporary characters portrayed in the scene. It was noticed that the bearded man holding his hands together in prayer is the same person as one of the Magi in the predella of the Pisa Polyptych, now in Berlin; furthermoree it has been suggested that it may be a portrait of Donatello, while others think that Donatello is the old man with a beard between St Peter and St John. According to another view this character is Giovanni, nicknamed Lo Scheggia, Masaccio's brother; while some believe that he is a self-portrait. The removal of the altar has uncovered a section of the painting, at the far right, which is of fundamental importance in understanding the episode: this section includes the facade of a church, a bell tower, a stretch of blue sky and a column with a Corinthian capital behind St John. Also extremely important is the way Masaccio conceived the right-hand margin of the composition. To give the space a more regular geometrical construction, Masaccio has created "a complex play of optical effects and of perspective, as we can see in the lower section of the window jamb, where he has solved graphically an architectural problem, pictorially adjusting the faulty plumb-line of the edge of the jamb and the end wall; he makes the story, and therefore some of the background constructions, continue on the jamb." The street, depicted in accurate perspective, is lined with typically mediaeval Florentine houses; in fact, the scene appears to be set near San Felice in Piazza, which had a commemorative column standing in front of it. But the splendid palace in rusticated stone looks like Palazzo Vecchio in the lower section (the high socle that we can still see on the facade along Via della Ninna, with the small built-in door), although it is much more similar to Palazzo Pitti in the upper part (the windows with their rusticated stone frames). And in some details, such as the exact geometrical scansion of the ashlars, it is an anticipation of later facades, first and foremost Palazzo Antinori.

|

||

St Peter Healing the Sick with his Shadow, (detail) 1426-27, fresco, 230 x 162 cm, Cappella Brancacci, Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence |

||

Compared to the situation before the recent cleaning, this is the fresco that appears to have benefitted the most from the operation: the splendid colour tones have been rediscovered, as well as the lighting and the draughtsmanship, justifying the fact that this fresco has always been considered a work of unparalleled beauty. Vasari wrote: " ... a nude trembling because of the cold, amongst the other neophytes, executed with such fine relief and gentle manner, that it is highly praised and admired by all artists, ancient and modern."

|

||

| Raising of the Son of Theophilus and St Peter Enthroned |

||

|

||

Masaccio, Raising of the Son of Theophilus and St Peter Enthroned, 1426-27, fresco, 230 x 598 cm, Cappella Brancacci, Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence |

||

| This scene illustrates the miracle that Peter performed after he was released from prison, thanks to Paul's intercession. According to the account in the Golden Legend, once out of prison, Peter was taken to the tomb of the son of Theophilus, Prefect of Antioch. Here St Peter immediately resurrected the young man who had been dead for fourteen years. As a result, Theophilus, the entire population of Antioch and many others were converted to the faith; they built a magnificent church and in the centre of the church a chair for Peter, so that he could sit during his sermons and be heard and seen by all. Peter sat in the chair for seven years; then he went to Rome and for twenty-five years sat on the papal throne, the cathedra, in Rome. Masaccio sets the scene in a contemporary church, with contemporary ecclesiastical figures (actually the Carmelite friars from Santa Maria del Carmine) and a congregation that includes a self-portrait and portraits of Masolino, Leon Battista Alberti, Brunelleschi. Vasari, in his Life of Masaccio, mentions the work of Filippino, but later chroniclers refer to all the frescoes in the chapel as by Masaccio. In the 19th century it was once again pointed out the work of Filippino, distinguishing it from that of Masaccio; and since then critics have been in almost total agreement with his theory. Scholars have suggested that Filippino was commissioned to complete the work that Masaccio had left unfinished or to repair sections which been damaged or destroyed because they depicted characters that were enemies of the Medici, like the Brancacci. There is no doubt that the Brancacci family was subjected to something similar to a "damnatio memoriae" after they had been declared enemies of the people and exiled. Vasari had already identified a number of contemporary figures in those painted by Filippino: the resurrected youth was supposedly a portrait of the painter Francesco Granacci, at that time hardly more than a boy; "and also the knight Messer Tommaso Soderini, Piero Guicciardini, the father of Messer Francesco who wrote the Histories, Piero del Pugliese and the poet Luigi Pulci." Studies of the possible portraits and of the iconography of the fresco confirmed the identifications made by Vasari and suggests others, presumably already planned in Masaccio's original sinopia, indicating that the fresco was intended to convey a political message: the Carmelite monk is a portrait of Cardinal Branda Castiglione; Theophilus is Gian Galeazzo Visconti; the man sitting at Theophilus's feet is Coluccio Salutati. And the four men standing at the far right are, starting from the right, Brunelleschi, Leon Battista Alberti, Masaccio and Masolino. |

||

|

Masolino da Panicale | Brancacci Chapel in Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence |

||

|

The chapel was recently superbly restored, with the removal of accumulated candle soot and layers of 18th century egg-based gum which had formed a mold. The frescoes have an intense radiance, making it possible to see very clearly the shifts in emphasis between Masolino's work and that of Masaccio (contrast the serenity of Masolino's Temptation of Adam and Eve with the excruciating agony of Masaccio's Expulsion of Adam and Eve from Paradise). Art in Tuscany | Masolino da Panicale

|

||

|

Filippo (Filippino) Lippi | Brancacci Chapel in Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence |

||

|

After the death of his father, Fra Filippo Lippi, when Filippino was 12, he entered the workshop of Sandro Botticelli and absorbed many aspects of his style. Art historians classify Filippino Lippi’s early pieces as reflective of Botticelli’s style. In the beginning, Lippi completed a fresco cycle at the Brancacci Chapel in Florence’s Santa Maria del Carmine. His efforts were a continuation of an unfinished project by Masolino and Masaccio.One of his most important assignments was the completion of the frescoes in the Brancacci Chapel in Florence's Santa Maria del Carmine (c. 1485 – 87), left unfinished when Masaccio died. |

||

|

||

Filippino Lippi, Disputation with Simon Magus and Crucifixion of Peter, 1481-82, Brancacci Chapel, Church of Santa Maria del Carmine in Firenze

|

||

Filippino's first major project was the completion of the fresco cycle begun by Masaccio and Masolino in the Brancacci Chapel, Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence, which had remained unfinished for more than half a century. Here Filippino adjusted his style to allow his contribution to seamlessly mesh with Masaccio's more monumental manner. Art in Tuscany | Filippino Lippi | Brancacci Chapel in Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence

|

||

|

||

Holiday accomodation in Tuscany | Podere Santa Pia | Artist and writer's residency

|

||||

Podere Santa Pia |

Podere Santa Pia, garden view, April |

View from Podere Santa Pia

on the coast and Corsica |

||

|

||||

Montefalco |

Santa Maria del Carmine, Firenze |

Sansepolcro |

||

| Vasari Corridor, Florence | Perugia |

Florence, Duomo |

||

|

||||

Podere Santa Pia, evening view on the Maremma from the western terrace |

||||

This page uses material from the Wikipedia articles Masaccio and Brancacci Chapel, published under the GNU Free Documentation License. |

||||