| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

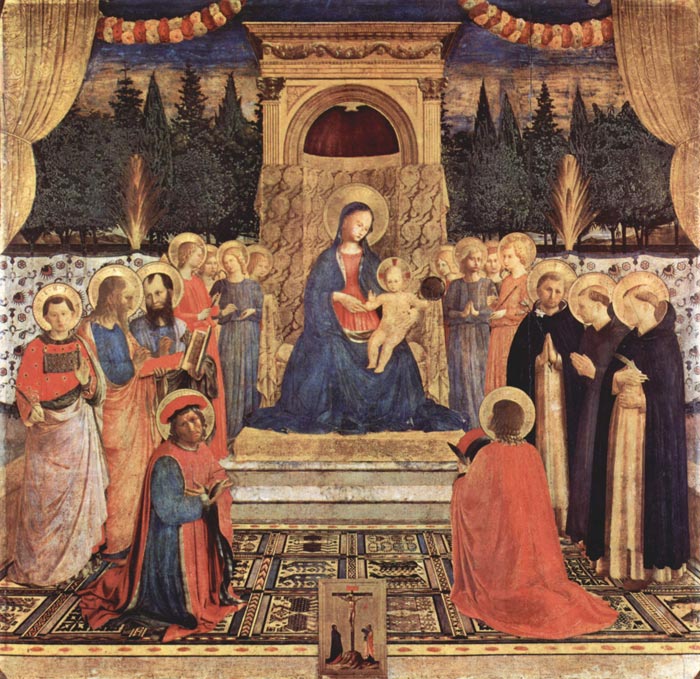

| Fra Angelico, San Marco Altarpiece: Madonna with Child, Saints and Crucifixion, about 1438-1440, Florence, Museo di San Marco

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

Fra Angelico | The San Marco Altarpiece 1438-1440

|

|

|

|

| |

|

The San Marco Altarpiece (also known as Madonna and Saints) is housed in the San Marco Museum of Florence, Italy. It was commissioned by Cosimo de' Medici the Elder, and was completed sometime between 1438 and 1443. In addition to the main panel depicting the enthroned Virgin and Child surrounded by Angels and Saints, there were 9 predella panels accompanying it, narrating the legend of the patron saints, Saints Cosmas and Damian. Only the main panel and two predella panels actually remain in the Convent of San Marco today. The San Marco Altarpiece is known as one of the best early Renaissance paintings for its employment of metaphor and perspective, trompe l'oeil, and the intertwining of Dominican religious themes and symbols with contemporary, political messages.

The rededication of the high altar to Saints Cosmas and Damian together with thez titular saint, San Marco, required the execution of a new altarpiece.

|

Medici Background

When the Dominican Order claimed ownership of the church and monastery of San Marco, they realized the buildings had been badly neglected and needed sponsorship to renovate the building. Cosimo de' Medici and his brother Lorenzo di Giovanni de' Medici took it upon themselves to hire architect Michelozzo to rebuild the monastery. As customary, they rededicated the church to include the patron saints, Saints Cosmas and Damian, as well as the original eponym, Saint Mark. The Medici patron saints were prominently included in the dedication to insist to the friars that Cosimo and his wealth played a vital role in the convent's establishment. After acquiring the patronage rights to the choir and high altar in 1438, the Medici brothers executed their plans to replace the existing altarpiece by Lorenzo di Niccolo with one of their own. Cosimo de' Medici commissioned a friar in the Dominican community by the name of Fra Angelico to paint the new altarpiece, as well as additional frescoes in the cells, corridors, and cloister of the rebuilt monastery. But the Medici not only earned the rights to the San Marco monastery, but to other churches as well, extending their territorial presence the whole length of the Via Larga, at the other end of which stood the family residences, and even sponsored the Feste de' Magi, an extravagant performance of Jesus's journey from Herod's Palace in Jerusalem to the stable in Bethlehem. The Medici's direct hand in the affairs of the Feste de' Magi, Florence as a symbol for the Holy Land, and San Marco as the final destination and the symbol of Bethlehem surely served to adulate the Medici position. For the Medici, the festival was more of a political instrument than anything else. Lay Florentine's would flock to San Marco to see the actual San Marco Altarpiece during the Festa de' Magi parade when the "Three Kings" entered the choir to pay homage to the Christ Child. The Medici's reign over San Marco and Cosimo's patronage were not just expressions of the Dominican Observance, but a foothold for political development as well.

Formal Analysis of the Painting

The San Marco Altarpiece depicts a portrait of the Virgin and Child seated on a throne surrounded by saints and angels. The formal elements are innovative for a contemporary Virgin and Child altarpiece as the positioning of the characters creates a deeply-receding and logical space in front of the landscape background. The pomegranate embroidered curtain behind the Virgin and Child establishes a distinct horizontal line separating the events depicted in the painting from the landscape behind it. The altarpiece is situated on the then newly-invented single rectangular panel, which helps turn a typical easel painting into the principle image of the altarpiece. Representing the figures set within a coherent pictorial space was also a new technique Angelico employed. While partially covered by the saints and angels, there is a definite line created by the carpet's receding squares in the foreground adding depth to the painting. Angelico's use of space is exceptional as he creates a sense of balance on both sides of the Virgin and Child, but also leaves available space on the carpet approaching the Virgin and Child so the viewer does not feel blocked or overwhelmed. This symmetry and order would allow worshippers to clearly view the painting from afar. He also employs naturalistic effects of light and color combined with a variety of colors and patterns. The natural colors contribute to the slightly darker complexion of the painting, which may accentuate the sacred holiness of the moment. His usage of the red and blue traditional colors of the Virgin and Saints Cosmas and Damian are noteworthy. By dressing both kneeling saints as well as several of the angels in red, Angelico creates a vertical link and further geometric stability. The symmetry resulting from the figures and colors allows the viewer to zoom-in and creates a smooth, continuous movement from figure to figure, eventually arriving at the Virgin and Child in the center. On the right, Saint Damian kneels on an inward angle towards the center praising the Virgin and Child, which draws the viewer's eyes towards the painting's vanishing point at the Virgin's chin. The Virgin and Child are featured precisely at the vertical and horizontal axes' intersecting points and are placed above Angelico's Trompe l'oeil depiction of the crucifixion. One may criticize Angelico for his imperfect use of scale. Though they are sitting on a pedestal, the Virgin and Child do not seem much larger than the rest of the characters, showing a lack of a scale setting the main subjects apart from other mortals. If anything, the Virgin and Child should be smaller due to their increased distance from the viewer. While he does create a sense of depth, the distance to approach the throne is minimal, which some historians perceive as a lack of awe for the holy figures. The altarpiece is thus seen as a radical departure from the vulnerable models known in Dominican art. One should also note that the San Marco Altarpiece is one of the earliest examples of sacra conversazione (sacred conversation), a type of image showing the Virgin and Child amongst saints in a unified space and single pictorial field, rather than setting them completely apart.

Saints in the Painting

The Saints play an integral role in the structure and program of the altarpiece. The two patron physician saints, Saints Cosmas and Damian, are the most commented on subjects of the painting as the intercessors between the Virgin and Child. The saints are kneeling most immediately in the foreground, making them larger than the remaining figures and signifying their importance. Saint Cosmas is seen as the primary interlocutor figure as he mirror's the viewer's glance, looking directly at the viewer. This establishes a sense of accessibility to the painting on the viewer's part. Saint Cosmas's representation pays homage to Cosimo de' Medici since it has been identified as a portrait of Cosimo himself. On the right, Saint Damian takes the expected kneeling pose of a Dominican worshipper showing reverent devotion. His positioning, as written above, helps contribute to the viewer's visual path towards the center of the painting. If one looks carefully, Saints Cosmas and Damian form two bases of a triangle whose apex is the Virgin and Child. On the far left, Saint Lawrence, representing Cosimo's brother Lawrence, too glances out towards the viewer as an invitation into the holy space of the Virgin and Child. He also represents Cosmas' deceased brother, Lorenzo. Next to Saint Lawrence is Saint John the Evangelist standing for both Cosimo's father, Giovanni di Bicci de' Medici and Cosimo's own son, Giovanni de' Medici. Saint Mark, the dedicatee of the church, is seen next to Saint John the Evangelist holding an open codex above Saint Cosmas's head, which is further discussed below (Symbols). The right side of the painting features Saint Dominic and Saint Peter the Martyr, the 2nd Dominican saint. The last saint on the right side is Saint Francis who stands for Cosimo's elder son Piero and most likely Lorenzo's son Pier Francesco.

Metaphors and Perspective

Two metaphors of perspective utilized in the San Marco altarpiece are the open window and the mirror. The open window metaphor of perspective implies continuity between real space and the space of the image and similarly, the mirror metaphor divides the real and the imaginary, suggesting a correspondence between the viewer's world and the fictive world of the painting. The fictive curtains in the upper corners of the painting for example, signal alterity (or otherness) of the scene by drawing attention to the surface. By unveiling the painted curtains, Angelico draws the viewer into the painting as if they were an audience watching a performance. At the same time however, the fact that the curtains are indeed present draws a line between observing the painting and entering the scene. The pax portraying Jesus's crucifixion is an exemplary use of Trompe l'oeil and creates another layer of the open window metaphor. As in most other paintings that employ this technique, Angelico makes it seem as if the pax actually resides on the picture's plane. It is a clear stop sign that allows the viewer to approach the painting, but only to a certain point. It reinforces the verisimilitude of the three-dimensional space behind it, simultaneously creating borders and blocking access to the fictive, heavenly space of the painting. Mirroring, as exemplified by the saints, helps establish a correlation between the world of the choir and the images in the painting itself. As aforementioned, the saints in the foreground mimic the viewer's glare towards the vanishing point, thus marking the viewers' presence, but only temporarily. When Saint Cosmas stares out towards the viewer, he acknowledges the viewer's presence, but there is nonetheless a boundary between the viewer and the divine scene. In other words, both the real and fictive worlds are connected and those in the real world are invited to observe but not fully participate in the ideal Heavenly world. The mirror metaphor thus allows the viewer to feel connected to the piece and the window metaphor gives the viewer a foretaste of a pictorial vision of heaven, but Fra Angelico also uses the crucifixion pax and curtains to remind the viewer of the closed, 'glazed' nature of the illusion. In this one painting, the metaphors of perspective produce simultaneous feelings of absence, presence, and reflection.

|

Symbols

|

|

|

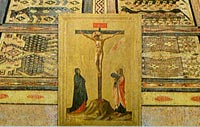

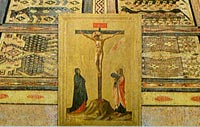

| In the early days of the Dominican Order, only sculpted or painted crucifixes were allowed on altarpieces. The crucifix remained a fundamental component to the altar's furnishings as it represented the closest parallel to the action of Mass and the consecration of the body and blood of Christ. The San Marco Altarpiece's crucifixion pax's gold background, archaistic figure, and almost gilded frame makes it clear that it is supposed to be seen as a separate painting. The fact that it enhances the naturalism of the work behind it because of its appearance as another painting, not an actual part of the scene, makes it a perfect example of Trompe l'oeil. In addition to the crucifixion pax itself, its placement in relation to the predellas below plays an important role. Angelico placed the Entombment of Christ predella directly under the crucifixion on the main panel, which gives the altarpiece a Eucharistic function. |

|

|

The positioning connects the crucifixion and entombment thematically and visually so that one succeeds the other. The crucifixion pax may also allude to a connection between Saints Cosmas and Damian as they too were condemned to the cross, as shown at the right end of the predella strip. The comparison of Christ to the patron saints elevates the patron saints further on a pedestal. The pax, thanks to the Trompe l'oeil effect, reminds the viewer that the worlds of Man and Christ are connected. Through the combination of religious and political innuendo, Angelico lauds the Medici family, insinuating that Divine Will determined their political fortunes of the city over which Cosimo was exercising more and more control.

St. Mark is depicted holding an open codex directly above Saint Cosmas's head. The book is a very important symbol as it links the two saints to original disciples of Jesus. The book is opened to Chapter 7 of Mark's Gospel in which the evangelist relays how Jesus preached in the synagogue and provoked astonishment. One line in the chapter says, "And they [the apostles] anointed with oil man that were sick and healed them." It is no mere coincidence that Angelico placed this healing text above the Saint Cosmas's head. As physician saints with healing abilities, Saints Cosmas and Damian are linked as disciples of Jesus. Angelico uses text in his altarpiece in an expansive and allusive way, going beyond the verses actually inscribed in the painting.

The landscape and garlands of roses have a liturgical component to them as well. Ecclesiasticus Chapter 24 says, "I was exalted like a cedar in Lebanon and as a Cyprus tree on Mount Zion. I was exalted like a palm tree in Cades and like a rose in Jericho, and as a fair olive tree in a pleasant field, and grew up as a plane tree by the water." The painted landscape contains various palm, cypress, orange, and pomegranate trees. The roses mentioned in the text hang in the altarpiece, almost by an invisible thread. In the back, velvet-soft hills ring the shore of a wide placid sea stretching beneath a cloud-filled sky to the horizon, just above the Virgin Mary and Child. One can surely infer that the landscape was not painted the way it was for simple aesthetic purposes, but to connect it to the liturgical Ecclesiasticus text as well.

In the very center of the picture, the nude Christ Child is portrayed as the King of Kings and Divine Ruler on his throne. His dependence on his mother's physical support is almost ambiguous. Jesus holds up his right hand in blessing and an orb in his left hand. Jesus's right hand, as seen in many other religious works, blesses all who aim their prayers and attention towards him, members of the choir included; it signifies his authority. His left hand holds the royal orb. This orb is a map of the world and upon close inspection, one can see that the Holy Land is marked by a star on the orb. This exemplifies the loyalty one would have towards Jesus and the faith one would have in his knowledge of the earth and how it should be run.

The curtains and roses featured in the upper corners of the altarpiece are very significant as well. The drawn curtains are pulled back beyond the sides of the frame, literally unveiling what is hidden behind. But because the curtains are not fully drawn, one can speculate that this fictive image of heaven is not one to be taken for granted because at any moment, the curtains may close. Similarly, the pendulous garlands of white, pink, and red roses emphasize the delicate, transitory scene. Just as flowers die without water, so too may the scene disappear if not appreciated enough.

The rich, elegant Anatolian carpet embellishing the royal enclosure bears the yellow border marked around by the red Medici palle. It also features the zodiacal Cancer and Pisces, possibly symbolizing the beginning and end of the Council of Florence. The carpet is just another way the Medici could make their statement of political power through religious art.

Religious Significance

Fra Angelico planned the San Marco Altarpiece's iconography around Dominican themes. Within the painting, Angelico references practices of the Dominican Mass. Just as the deacon and subdeacon knelt while helping the Dominican priest during Mass, Saints Cosmas and Damian kneel in this altarpiece. The priest would also stand in the center of the altar during Mass to reenact the sacrifice of Christ. Angelico incorporates this religious practice through the vertically directed pax of the crucified Christ in the center to lead the viewer’s eyes to Mary holding Jesus. The saints surrounding the Virgin and Child seem representative of the Dominican Congregation at large.

Dominican altarpieces traditionally stressed the Dominican Order’s relationship to Christ and the apostles. The Dominicans saw Christ as playing an intermediary in the relationship between Man and God. In Dialogue, Dominican Saint Catherine of Siena wrote "Christ is a bridge stretching from heaven to earth, joining the earth of man’s humanity with the greatness of the Godhead." The crucifixion pax, which as aforementioned is used to allow the viewer to approach the painting to a certain point, also bridges Christ's Passion and the world of God to the world of Man. It emphasizes the remoteness of the painted realm, but also the possibility of transcendence through Christ and sacrifice.

Matin's Hymn is another text Angelico alludes to in the painting. The hymn says, "He who made all things held the whole world in his hand, even while in his mother’s womb." The positioning of the Child in the San Marco Altarpiece is connected to this text. As Jesus sits nakedly on his mother's lap and grasps the royal orb and map of the world in his left hand, there is sense of vulnerable infancy given to him as if he were still dependant on his mother in her womb, but he nonetheless literally possesses the world in his hands, no matter how young he is.

Saint Thomas Aquinas, one of the greatest Dominicans to have lived composed the Latin phrase, “Contemplata Aliis Tradere,” which translates as "To pass on to others the things contemplated." Saint Mark's open codex which discusses Christ sending his disciples to preach relates to this text.Saint Mark turns the strictly theological and liturgical aspects of the altarpiece ("things contemplated") towards their end in preaching ("passing it on to others"). Saint Aquinas also said that the sacrament of the Eucharist creates a spiritual community that is an imperfect version of that enjoyed by saints in heaven, which is very much reminiscent of the San Marco Altarpiece's layout.

The direct allusions to Dominican practices and other religious symbols complement Vasari's observation that Fra Angelico's artistic symbols and figures express the depth and sincerity of his Christian piety.

Restoration Issues

One problem with the San Marco Altarpiece as it exists today is the fact that it faced a major cleaning in the 19th Century. The cleaning using caustic soda consequently rubbed off the surface of the painting down to the underpainting. This caused the painting to lose much of its glaze that imparted the nuances of light and color. Any subtle modulations of color and light Angelico used to heighten the still-moving pathos of faces like that of St. Lawrence were removed. There are still minor traces of cast shadows towards the bottom edges of the draperies in the painting, which are indicative of how Angelico gave the medieval equation of earthly and heavenly beauty new immediacy by translating it into the rational language of a representational style. In addition, as Angelico implies in other ways, glazing was a technique used to create yet another boundary between the real world and the pictorial illusion.

|

|

|

|

| |

|

The San Marco Altarpiece was removed and dismembered in the seventeenth century during the renovation of the church belonging to the Convent of San Marco and dedicated to the two medical saints, Cosmas and Damian. In addition to the main painting representing the Virgin and Child Enthroned with Angels and Saints, there were 9 predella pictures, seven in the front and two on the lateral sides. Only two of the predella paintings remained in the Convent, all the others are now in different museums (in Washington, Munich, Dublin and Paris).

Based on the results of thorough research, scholars agreed in the reconstruction of the altarpiece. The predella pictures depict the story of Saint Cosmas and Saint Damian on eight small panels, while the nineth, located in the centre, represents the Entombment (Pietà). The narratives that extended continuously across the foot of the altarpiece were conceived with great imagination as well as geometric rigour.

Saints Cosmas and Damian were brothers, born in Arabia in the third century. Saint Gregory of Tours wrote that they were twins. They studied the sciences in Syria, and became eminent for their skill in medicine. Being Christians and filled with the charity which characterizes our holy religion, they practiced their profession with great application and wonderful success, but never accepted any fee. Their most famous miraculous exploit was the grafting of a leg from a recently deceased Ethiopian to replace a patient's ulcered leg, and was the subject of many paintings and illuminations.

During the persecution under Diocletian, Cosmas and Damian were arrested by order of the Prefect of Cilicia, who ordered them under torture to recant. However, according to legend they stayed true to their faith, enduring being hung on a cross, stoned and shot by arrows and finally suffered execution by beheading.

Sts Cosmas and Damian are regarded as the patrons of physicians and surgeons and are sometimes represented with medical emblems.

|

|

| Fra Angelico, Predella of San Marco Altarpiece, Beheading of Saint Cosmas and Saint Damian, 1438-40,

tempera on wood, 36 x 46 cm, Musée du Louvre, Paris

|

On this picture, which was placed on the left lateral side of the predella, two consecutive episodes are shown. On the left the two Arab physicians effect a miraculous cure; on the right Saint Damian, contrary to his vows, unwillingly accepts a gift.

|

|

Fra Angelico, Predella of San Marco Altarpiece, The Healing of Palladia by Saint Cosmas and Saint Damian, National Gallery of Art, Washington

|

Saint Cosmas and Saint Damian before Lisius is the first panel from the left on the predella. |

|

Fra Angelico, Predella of San Marco Altarpiece, Saint Cosmas and Saint Damian before Lisius, Alte Pinakothek, Munich

|

Saint Cosmas and Saint Damian Salvaged is the second panel from the left on the predella.

In Saint Cosmas and Saint Damian Salvaged the saints' prayer to God, the judge's attack by demons and their salvation by angels are represented in varied scale throughout the landscape to connote different moments in time. The undulating forms of the landscape recede and flatten as they approach the horizon, itself dissolved in the mist of atmospheric perspective. The figures are more intensely characterized through their varied ages, garments, postures and expressions. |

|

Fra Angelico, Predella of San Marco Altarpiece, Saint Cosmas and Saint Damian Salvaged, Alte Pinakothek, Munich

|

Saint Cosmas and Saint Damian Condamned, is the third panel from the left on the predella. |

|

Fra Angelico, Predella of San Marco Altarpiece, Saint Cosmas and Saint Damian Condamned, National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin

|

Entombment, the centre predella panel of the San Marco altarpiece is not overtly connected to the scenes on either side of it, which show the life of Sts Cosmas and Damian, although it too is lit from the right. Instead it relates directly to the crucifixion at the base of the altarpiece which, when the predella was in situ, was immediately above it. Christ's body is supported by Nicodemus, and his hands are held and kissed by the stooping Virgin and St John. Christ has a weightless air about him, so that the three other figures appear to have to do little to support him. The winding cloth lies stretched out in a receding rectangle creating the foreground space, its folds and colour echoing the white rock. Behind lies the dark rectangular void of the tomb. The sparsity and simplicity of the composition, the firmly closed-off space and the extensive use of white in this panel, are all also found in Angelico's frescoes at San Marco.

The figures here, arranged parallel with each other, with the central perspective of the shroud leading to the tomb, shows a very different idea of spatial organization from that in Rogier van der Weyden's panel of the same subject.

|

|

Fra Angelico, Predella of San Marco Altarpiece, Entombment, Alte Pinakothek, Munich

|

Saint Cosmas and Saint Damian Crucifixed and Stoned is the third panel from the right on the predella. |

|

Fra Angelico, Predella of San Marco Altarpiece, Saint Cosmas and Saint Damian Crucifixed and Stoned, Alte Pinakothek, Munich

|

The Beheading of Cosmas and Damian is the second panel from the right on the predella. The legend of Sts Cosmas and Damian, twin brothers who were famed for making no charges for their services as physicians, is outlined in the predella panels of this San Marco altarpiece. Several attempts to put them to death failed, until the last, pictured here. The final moments of the two brothers are shown set against one of Angelico's finest landscapes. Outside a town with fortifications akin to those of Jerusalem in his Deposition, the two saints wait to join the three headless figures in the foreground. The greatest emphasis falls on the one who kneels directly in front of a row of five cypresses which runs parallel to the picture plane. The trees can be taken to symbolize the five being executed.

|

|

Fra Angelico, Predella of San Marco Altarpiece, Beheading of Cosmas and Damian, Paris, Musee du Louvre

|

The Sepulchring of Saint Cosmas and Saint Damianis the first pucture from the right on the predella. |

|

Fra Angelico, Predella of San Marco Altarpiece, Sepulchring of Saint Cosmas and Saint Damian, Museo di San Marco, Florence

|

The Healing of Justinian by Saint Cosmas and Saint Damian was placed on the right lateral side of the predella. Justinian sleeps while Sts Cosmas and Damian enter his chamber trailing patches of soft cloud. They replace his corrupted leg with a healthy one. The room is Spartan but the variety of light-sources and Angelico's close observation give it interest. Light floods in from outside through the window on the left, illuminating its own frame and parts of the swags of curtain. Exterior space is indicated not only by the window but by the door opposite it, from whence comes more light. From the front left outside the picture comes the third source of light, which produces a broad diagonal sweep across the right wall. The curtain provides the rectangular backdrop parallel to the picture surface which is common to each of these predella panels, and also hints at more, obscured space behind it. The container hanging from a nail on the side of the bed, the glass and decanter, the slippers and the simple three-legged stool, all provide the constituents of a closely observed still-life. |

|

Fra Angelico, Predella of San Marco Altarpiece, The Healing of Justinian by Saint Cosmas and Saint Damian, Museo di San Marco, Florence |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Fra Angelico in Palazzo Strozzi en Museo San Marco

Beato Angelico a Palazzo Strozzi e Museo di San Marco

26

September - 25 Januari 2026

The exhibition "Beato Angelico" at Palazzo Strozzi and the Museo San Marco explores the work, development, and influence of Beato Angelico's art, as well as his relationships with painters such as Lorenzo Monaco, Masaccio, Filippo Lippi, and sculptors like Lorenzo Ghiberti, Michelozzo, and Luca della Robbia.

It is the first major exhibition in Florence dedicated to the artist exactly seventy years after the 1955 monograph.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Palazzo Strozzi, Firenze

|

|

Beato Angelico, mostra Palazzo Strozzi and Museo di San Marco, Firenze, 2025

|

|

Museo di San Marco, veduta posteriore

|

|

|

|

|

![Beato Angelico, panoramica della mostra con la Pala d'altare di San Marco ( 1438-1442) e la Pala di Annalena (1445 circa), Palazzo Strozzi, Firenze, 2025 [Photo: Ela Bialkowska, OKNO Studio]](https://lh3.googleusercontent.com/pw/AP1GczNBKAgi43MEhBHit3vK00YmiyRsTYQyXCemfRlLigP3CbVRrtBKkgplBTE7YAe4t75NoduxM-cz6UJYpKkyI_au_xMMOAZCkya_mWyNo7UG0rmBYveg=w2400-h1600-p-k) |

Beato Angelico, la grande mostra a Palazzo Strozzi, Firenze, sala 1

|

|

Beato Angelico, veduta della mostra, sala 6, Bernardo Rossellino, Pala di Mariotto d’Angelo (1434) e L'Annunciazione di Cortona (1430 ca.) di Beato Angelico, Palazzo Strozzi, Firenze, 20255

|

|

Beato Angelico, panoramica della mostra con la Pala d'altare di San Marco ( 1438-1442) e la Pala di Annalena (1445 circa), Palazzo Strozzi, Firenze, 2025

|

Giorgio Vasari | Lives of the Most Eminent Painters Sculptors and Architects, Fra Angelico | Detailed biography of the artist

Kanter, Laurence B., et al. Fra Angelico (exh. cat.) New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005.

Kanter, Laurence B. and Barbara Drake Boehm (eds.). Painting and Illumination in Early Renaissance Florence: 1300-1450 (exh. cat.). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1995.

Hood, William. Fra Angelico at San Marco. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1993.

Ames-Lewis, Francis. The Early Medici and Their Artists. London: Birkbeck College, 1995.

Nygren, Barnaby. "Fra Angelico's San Marco Altarpiece and the Metaphors of Perspective." The Source. Fall 2002, v.22.1, p. 25-32.

Douglas, Robert Langton. Fra Angelico. London: G. Bell and Sons, 1997.

Rab Hatfield, “The Compagnia de’ Magi,” Journal of the Warburg and Caurtauld Institutes 33 (1970)

Hood, William. Fra Angelico at San Marco. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993.

Lévy, Allison Mary, Re-membering masculinity in early modern Florence. Widowed Bodies, Mourning And Portraiture, Ashgate Publishing, 2006.

'From Pliny to Petrarch to Pope-Hennessy and beyond, many have understood the obvious connection between portraiture and commemorative practice. This book expands and nuances our understanding of Renaissance portraiture; the author shows it to be complexly generated within a discourse of male anxiety and pre-mortuary mourning. She argues that portraiture could defer memory loss or, at the very least, pictorially console the subject against his own potentially unmourned death. This book recognizes a socio-cultural anxiety - the fear not merely of death but also of being forgotten - and identifies a set of pictorial, literary and theoretical strategies consequently formulated to ensure memory. To explore this phenomenon, this interdisciplinary but fundamentally art historical project merges early modern visual culture and critical theories of the body. The author examines an extensive selection of fifteenth- and sixteenth-century male and female portraits, primarily associated with the Medici family, circle and court, in and against both historical writings and contemporary discourses, including literary and cultural theory, psychoanalysis, feminism and gender studies, and critical theories of race and disability. "Re-membering Masculinity" generates new ideas about both male and female portraiture in early modern Florence, raises even more questions about the experiences and representations of widowhood and mourning, and re-configures our understanding of masculinity - from the early modern male body to 'Renaissance Man' to postmodern manhood.'

Miller, Julia Isabel. "Medici Patronage and the Iconography of Fra Angelico's San Marco Altarpiece" Studies in Iconography 1987, v.11, p. 1-13.

Miller, Julia Isabel. "Major Florentine Altarpieces From 1430 to 1450 (Italy)." New York: Columbia University, 1984.

Saward, John. The Beauty of Holiness and the Holiness of Beauty: Art, Sanctity, and the Truth of Catholicism. San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1997. Extended theological meditation of the San Marco Altarpiece.

'In the main field of the altarpiece, the Madonna and Child are shown enthroned beneath a classical niche of recognizably Michelozzian design. Eight angels and eight saints are distributed with calculated simplicity on either side of the throne. The foreground is covered by a magnificent carpet inlaid with zodiacal symbols. The two kneeling saints can be identified by their costumes as Cosmas and Damian. Their prominence underscores the importance of Cosimo de Medici, the patron of the altarpiece and of the renovations at San Marco. On January 6, 1443, this altar was rededicated to these two saints together with Saint Mark.'

Spike, John Spike, Abbeville Press, New York, 1997.

Stockstill, Wendy Leiko. "Cosimo de' Medici and his quest for salvation as seen in the monastery of San Marco, the Medici Palace Chapel, and the Church of San Lorenzo" California: California State University, Long Beach, 2008.

Strehlke, Carl Brandon,“Reviewed Work of Fra Angelico at San Marco,” The Burlington Magazine Vol. 135, No. 1086, Sep 1993 pp. 634-636

Illustrations of The Golden Legend from the HM 3027 manuscript of Legenda Aurea from the Huntington Library | dpg.lib.berkeley.edu

[Jacobus de Voragine, Cosmas and Damian, attaching the black leg to the sick man, Henry E. Huntington Library and Art Gallery, San Marino, California]

|

[1] Guido di Pietro was born in the northern countryside of Florence at the end of the Fourteenth Century. Between 1419 and 1422, he joined the Dominican monastic order and took the name Fra Giovanni. Following the departure of the artistic prodigy Masaccio (1401-1428) from Florence to Rome in 1427 (he died one year later under mysterious circumstances, possibly having been poisoned by a despicable rival), Fra Giovanni became the preeminent painter of remarkable altarpieces and other religious works in Tuscany for nearly 30 years. Called "pictor angelicus" or "Angelic Painter" shortly after his death in 1455, this title was later translated into English as Fra Angelico.

[2] Saints Cosmas and Damian were brothers, born in Arabia in the third century, of noble and virtuous parents. Saint Gregory of Tours wrote that they were twins. They studied the sciences in Syria, and became eminent for their skill in medicine. Being Christians and filled with the charity which characterizes our holy religion, they practiced their profession with great application and wonderful success, but never accepted any fee. They were loved and respected by the people for their good offices and their zeal for the Christian faith, which they took every opportunity to propagate.

When the persecution of Diocletian began to rage, it was impossible for persons of such distinction to remain concealed. They were denounced to the governor of Cilicia, named Lysias, as “Christians who cured various illnesses and delivered possessed persons in the name of the one called Christ; they do not permit others to go to the temple to honor the gods by sacrifices.” The two brothers were apprehended by the order of the governor, and after various preliminary torments were sentenced to be bound hand and foot and thrown into the sea. Their prayer has been conserved: “We rejoice, Lord, to follow the path of Your commandments, as in the midst of immense riches; and even though we walk through the valley of the shadow of death, we fear no evil.” And they recited the 23rd Psalm. The sentence was accomplished, but an Angel untied their bonds and drew them out of the sea. The witnesses of this fact returned to announce to the governor what had happened. They were brought back to Lysias as magicians, and he decided to imprison them until he could decide upon their fate.

He condemned them to be burnt alive, but they prayed to God to manifest His power, lest His name be blasphemed, and an earthquake moved the fire into the midst of the pagans and spared the martyrs. When the rack also left them unharmed, the prefect swore by his gods he would continue to torture them until they became the food of birds of prey. They were crucified and stoned by the people, but this and still other tortures were ineffectual. They were finally beheaded with three Christian companions.

Source: Les Petits Bollandistes: Vies des Saints, by Msgr. Paul Guérin (Bloud et Barral: Paris, 1882), Vol. 11.

|

|

Jacobus de Voragine, Cosmas and Damian, attaching the black leg to the sick man, Henry E. Huntington Library and Art Gallery, San Marino, California Jacobus de Voragine, Cosmas and Damian, attaching the black leg to the sick man, Henry E. Huntington Library and Art Gallery, San Marino, California

|

The saints are usually shown in similar or identical garments and often wear hats like those seen at left. Sometimes medical instruments appear as their attributes.

"As recounted in the Golden Legend, Sts Cosmas and Damian, third-century twin brothers and physicians-turned-martyrs, posthumously encounter a man, the Deacon Justinian, whose leg has been badly infected by a cancer:

While he was asleep, the two saints appeared to their devoted servant, bringing salves and surgical instruments. One of them said to the other: 'Where can we get flesh to fill in when we cut away the rotted leg? The other said: 'Just today an Ethiopian was buried in the cemetery of Saint Peter in Chains. Go and take his leg, and we'll put it in place of the bad one.

So he sped to the cemetery and brought back the Moor's leg, and the two saints cut off the sick man's leg and inserted the Moor's in its place. Finally they took the amputated leg and attached it to the body of the dead Moor. The man woke up, felt no pain, put his hand to his leg, and detected no lesion. He held a candle to the leg and could see nothing wrong with it, and began to wonder whether he was himself or someone else. Then he came to his senses, bounded joyfully from his bed, and told everyone about what he had seen in his dreams and how he had been healed.

They sent at once to the Moor's tomb, and found that his leg had indeed been cut off and the aforesaid man's limb put in its place in the tomb.

In abbreviated form, Sts Cosmas and Damian, having amputated the cancerous leg of the deacon, exhume a recently buried Moor, amputate his leg, and attach it to the sick white body before reburying the black one. The deacon wakes up and is unable to remember 'whether he was himself or someone else. The Moor's body is exhumed a second time, and the presence, there, of the cancerous white leg confirms the miracle. In more critical terms, in an effort to make whole again the vulnerable male body, the diseased white limb is compromised and replaced with the severed black limb; and vice-versa, the decayed white leg is transferred to the presumably once healthy though now dead - yet disturbingly disposable - black body."

Allison Mary Lévy, Re-membering masculinity in early modern Florence. Widowed Bodies, Mourning And Portraiture, Ashgate Publishing, 2006, p. 4.

The Golden Legend or Lives Of The Saints, compiled by Jacobus de Voragine, Archbishop of Genoa, 1275. Englished by William Caxton, First Edition 1483.

The lives of of Saints Cosmas and Damian in the Golden Legend #143: html or pdf

Illustrations of The Golden Legend from the HM 3027 manuscript of Legenda Aurea from the Huntington Library | dpg.lib.berkeley.edu

[Jacobus de Voragine, Cosmas and Damian, attaching the black leg to the sick man, Henry E. Huntington Library and Art Gallery, San Marino, California]

Art in Tuscany | The Golden Legend (Legenda aurea or Legenda sanctorum)

|

Holiday houses in Tuscany | Podere Santa Pia

|

|

|

|

|

|

Podere Santa Pia, mystic holiday home in the heart of the Tuscan Maremma

|

|

Casa Vacanze Podere Santa Pia, Castiglioncello Bandini, Toscane

|

|

Colline sotto Podere Santa Pia con ampia vista sulla Maremma Grossetana

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pools in a natural area, a dive into the heart of Tuscany

|

|

A beautiful spring morning by the pool, a natural jewel nestled amidst the verdant Tuscan hill

|

|

The night pool at Podere Santa Pia exudes a hypnotic sense of purity

|

|

|

|

|

|

Florence, San Miniato al Monte |

|

Florence, Duomo |

|

Florence, Santa Croce |

| |

|

|

|

|

This page incorporates text from the article Angelico, Fra by William Michael Rossetti, in the Encyclopædia Britannica, Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain, and uses material from the Wikipedia articles Fra Angelico and San Marco Altarpiece published under the GNU Free Documentation License.

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Fra Angelico, Predella of San Marco Altarpiece, Beheading of Cosmas and Damian, Paris, Musee du Louvre

Fra Angelico, Predella of San Marco Altarpiece, Beheading of Cosmas and Damian, Paris, Musee du Louvre

Jacobus de Voragine, Cosmas and Damian, attaching the black leg to the sick man, Henry E. Huntington Library and Art Gallery, San Marino, California

Jacobus de Voragine, Cosmas and Damian, attaching the black leg to the sick man, Henry E. Huntington Library and Art Gallery, San Marino, California