In 1345, Ambrogio Lorenzetti created a world map, the mappamondo in Siena's Palazzo Publico. The Sala del Mappamondo (the World Map Room), used to be the headquarters of the Council of the Republic. The room was so-called after the enormous wooden disc by Ambrogio Lorenzetti, depicting the territory of the Republic. Of very large dimensions (roughly 4.83 m in diameter) and round in its form, it was mounted on a single, central pivot and rotated to bring, successively, various portions nearer to the viewer. The Sienese desire to have such an image relates to the popularity of written 'geographies' and the appearance of portolan maps in the late thirteenth century. In a way, the mappamondo might be styled the epitome of the Sienese interest in images and imaging. If Ambrogio's decorations in the Sala dei Pace laid before viewers Siena idealized, Ambrogio's map brought the world under their gaze.

Recent archival finds indicate that, rather than a mappamondo, it was a map of the Sienese state, a carta tapografica, painted around 14-24- and enlarged once in14-59 and quite possibly at other times, that was actually located here. [0]

The Sala del Mappamondo off the chapel contains two of Simone Martini's greatest works. On the left is his masterpiece, Maestà. Incredibly, this was his very first painting, finished in 1315 (he went over it again in 1321). Cleaned and restored in the early 1990s, it's the next generation's answer to Duccio's groundbreaking work on the same theme painted just 4 years earlier and now in the Museo dell'Opera Metropolitana. Martini's paintings tend to be characterized by richly patterned fabrics, and the gown of the enthroned Mary is no exception.

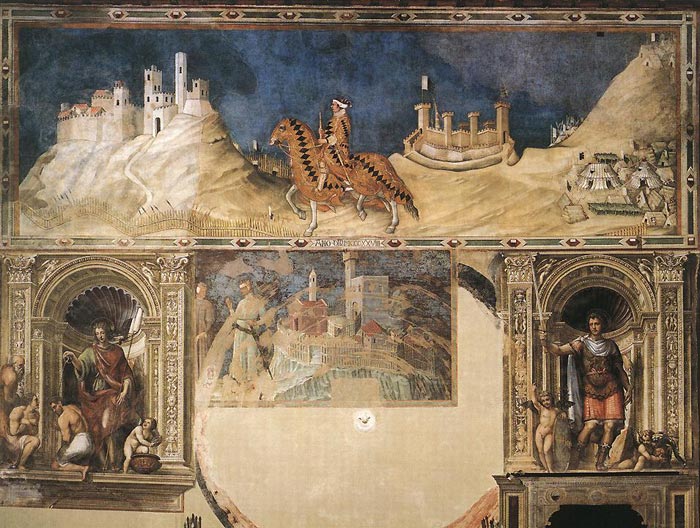

Those fabrics can be seen again across this great hall in Simone Martini's other masterwork, the fresco of Guidoriccio da Fogliano, where the captain of the Sienese army rides his charger across the territory he has just conquered (Montemassi, in 1328). Recently, art historians have disputed the attribution of this work to Martini, claiming that it was either a slightly later work or even a 16th-century fake. Part of what sparked the debate was the 1980 discovery of another, slightly older scarred fresco lower on the wall here. This earlier painting depicts two figures standing in front of a wooden-fenced castle. Some claim this is the fresco Martini painted, while those who support the authenticity of the Guidoriccio attribute this older fresco to Duccio, Pietro Lorenzetti, or Memmo di Filippuccio.

|

All that remains of the Mappamondo that Ambrogio Lorenzetti painted in 1345 for the Palazzo Pubblico, Siena, are the markings left by its installation on the wall opposite Simone Martini's Maestà. Disturbingly absent/present, this ghost of a work does not have to remain a casualty of endless debate on the fresco of Guidoriccio above. Medieval cartographic genres and traditions of map display can be applied toward a fresh interpretation of the lost Lorenzetti. By the same token, the wheel map opens discussion of the processes by which a changing configuration of images articulated a mythology of the Sienese state.

The world map that Ambrogio Lorenzetti painted in 1345 for the communal palace of Siena has long since vanished, but not without leaving spectacular traces of its unique design. A rotating wheel, the work scratched a series of great concentric rings into the surface of the wall on which it hung, thereby damaging a prior layer of painting concealed beneath. These rings and other aspects of its installation were discovered in 1980-81 when the fresco of Guidoriccio da Folignano was subjected to technical examination. In the middle register of the wall just below the image of the war captain, conservators exposed to view a previously unknown trecento fresco of the highest quality. The newly revealed scene, two men in the act of surrendering a town (hereafter referred to as the "New Town"), bears the imprint of the revolving map that superseded it. A fresco border painted in black around the circumference of the wheel, and serving to integrate it into a system of monumental mural decoration, was also partially recovered. As far as the cartographic image itself is concerned, a scarred patch of earlier painting admittedly amounts to an empty cipher. Yet the visible signs of the work's display and use, exceptional in the fragmentary history of medieval cartography, mitigate the absence of the monument that gave to the council hall its popular name, the Sala del Mappamondo.

To date, study of Lorenzetti's map has focused on reconstructing its intriguing pictorial content. Several generations of scholars have sought to visualize the lost image by mining archival sources, glossing apparently conflicting descriptions, and identifying later works for which it may have served as model. Since the recent restoration campaign, attention has been given to how physical evidence of the map's installation may bear upon the superposition, and hence relative dating, of the paintings on the Guidoriccio wall. In what follows, I shall attempt to open the discussion to broader issues raised by the map's enigmatic relation to known cartographic traditions, its location in the Palazzo Pubblico, and its rotary operation.

The first part of the study reviews the documentation concerning the map in order to clarify its physical nature. Here, the tradition of medieval display maps puts into new perspective the minimal clues about the Lorenzetti with which we are now sadly left. With regard to the cartographic image itself, the second part considers the crucial problem, not heretofore adequately addressed, of how the wheel's rotation would have been implicated in the formal depiction of the world. For the revolving map to have worked visually, its pictorial composition, including any writing, must have met the demands of a shifting orientation. With this in mind, it may be possible to single out a specific class of maps as Lorenzetti's most likely point of departure. The development of a particular cartographic genre, I am proposing, underlay the very possibility of the commission. We cannot hope, nor perhaps should we try, to reconstruct the "look" of Lorenzetti's painting. But the artistic context that enabled the con(re)ception of such an extraordinary work can be interrogated.

Parts three and four explore the work's production of meaning as a function of its place within a constellation of framing images. Surrounding pictorial material activated the signifying potential of both the cartographic image and its performance as a wheel. On these two levels also, Lorenzetti's painting reciprocally engaged earlier decoration in the hall to new ends. Just as the wheel map revised or expanded on ideas previously articulated in the Sala del Consiglio, so also it was in turn incorporated into a continuously evolving ensemble. Recalling the role of mappaemundi both in ecclesiastical and royal settings, the Sienese treatment of the theme displaced age-old traditions to further the secular ideology of the commune. Lorenzetti's map contributed to the elaboration of a civic agenda by appropriating competing discursive regimes. Finally, I suggest in part five that the Mappamondo may have been part of a programmatic transformation of the Sala del Consiglio itself.

The Cartographic Artifact

Scholars agree on some basic features of Lorenzetti's map. The great majority of specialists visualize it as a rotating disk located on the Guidoriccio wall below the equestrian figure, where the scoring is now visible. Predictably, Gordon Moran and Michael Mallory, who deny the authenticity of the Guidoriccio, argue a different view. But holding the Mappamondo hostage to the Guidoriccio, as Moran and Mallory do, will not help advance understanding of either work.

The written evidence may be easily summarized. The date of the commission and its attribution to Ambrogio are first recorded in the chronicle of Agnolo di Tura del Grasso at the end of a series of miscellaneous entries for the year 1345: "El Napamondo, che e in palazo de' segnori di Siena fu fatto in questo anno; fecelo maestro Ambruogio Lorenzetti dipentore da Siena." The Concistoro authorized the restoration of the Mappamondo in 1393. The substantial sum paid then to three painters for their colors, including azure, suggests a pictorial surface of monumental proportions. A glass window was ordered to be made "iuxta mappamundum" in 1413. When preaching in the Campo in 1427, Saint Bernardino of Siena reminded his audience of the image of Italy "nel Lappamondo." Ghiberti called Lorenzetti's work in the Palazzo Pubblico a cosmografia - a term he used both as a synonym for a map of the inhabited world and as the title for Ptolemy's Geography. Remarking on what could only be the same work, the Sienese antiquarian Sigismondo Tizio (1455-1528) retained the term mappamundi entrenched in local tradition, whereas later in the sixteenth century Vasari followed Ghiberti in referring to the Lorenzetti as a cosmografia.

So far as I am aware, Tizio, writing in the mid-1520s, provides the earliest description of the map's rotation and location: "Hoc vero anno [1344] mappamundum volubilem rotundumque in aula secunda balistarum publici palatii ille Vir [Ambrosius Laurentii] fecit. Pinxerat quoque aulam primam in scalarum primarum vertice, quae aula pacis nuncupatur" (In the year 1344 Ambrogio Lorenzetti made a turning, circular map of the world in the second hall of armaments in the Palazzo Pubblico. He also painted the first room [of armaments] at the top of the stairs, which is called the hall of peace). Two chambers on the second floor of the Palazzo Pubblico displayed armaments: the Sala del Consiglio and the adjoining Sala dei Nove, or meeting room of the ruling oligarchy, which had come to be called the Sala della Pace after Lorenzetti's famous Good Government. Both rooms were sometimes alternatively designated "Sala delle Balestre." Tizio distinguishes them in the order of their proximity to the stairs and further indicates that it is the second such room, i.e., the Sala del Consiglio, as opposed to the first or Sala della Pace, which contains the mappamundus volubilis. In a volume of addenda to his history, Tizio moreover specifies that the Mappamondo hung on the Guidoriccio wall below the equestrian image: "Hic ille [Guido Riccius] est, qui in aula Dominorum Senensium pictus est in Capite Mappe Mundi rotunde, ubi Montis Massici picta est obsidio" (Here is Guidoriccio, who is painted in the hall of the Sienese lords above the circular world map, where the siege of Montemassi is painted). The placement of the Mappamondo below the Guidoriccio is reiterated in an early seventeenth-century source. Where Tizio saw the Mappamondo, we now see the pattern of concentric rings scored into the wall.

The Mappamondo so dominated its spatial setting that it eventually dictated the name of the hall. Although I have been unable to find the appellation "Sala del Mappamondo" in official records before 1534, it may have become a popular term of reference at an earlier date. The object now silhouetted on the Guidoriccio wall, measuring about 15 feet 10 inches (4.83 m) in diameter, was sufficiently imposing in size to have been the Mappamondo. By Tizio's day, the Mappamondo may have already been cut down to make way for the current doorway between the Sala del Mappamondo and Sala dei Nove. Certainly by 1529 it was reduced in size to accommodate Sodoma's fresco of Saint Victor at right.

Eighteenth-century descriptions introduce new elements, but the discontinuity is not strong enough to warrant the conclusion that they refer to a different work. G. A. Pecci, G. Faluschi, and G. della Valle, it is true, depart from the vocabulary used by earlier witnesses: they speak of a "carta topografica nella quale appariva delineato tutto lo Stato di Siena." I shall address the import of their description in the following section. My point here is that their similar accounts of the object's rotation confirm they were looking at the same mappamundus volubilis as Tizio. Using slightly varying phrases, all three writers compare the map to a turning wheel: "si vede un' avanzo molto lacero di carta topografica . . . fatta a guisa di ruota da potersi muovere e girare."

The 1980-81 restoration campaign provided incontrovertible physical evidence that the circle imprinted on the Guidoriccio wall was occupied by a revolving disk. As specified in the eighteenth-century sources, it indeed turned on a single pivot, or stylus, by which it was affixed to the wall. The height at which the disk was installed suggests that its rotation could be effected manually from the floor. In his Lettere Senese of 1785, della Valle echoes Pecci (1730, 1752) and Faluschi (1784) in reporting "un avvanzo molto lacero di carta topografica," but adds that it was painted "in tela, di cui ora non resta che qualche piccolo cencio." Evidently eighteenth-century witnesses had before them merely a scrap of the map. The topographic depiction of the Sienese state then visible could thus have been but a small fragment of the whole.

The cumulative evidence leads to the conclusion that the rotating disk beneath the Guidoriccio was Lorenzetti's Mappamondo. In contrast, the argument put forward by Moran and Mallory is rather weak. They believe that the rings scratched into the intonaco of the "New Town" and circular border in fresco correspond not to the Lorenzetti work of 1345, but rather to a representation of the Sienese state commissioned in 1424. Based on his reading of a mid-fifteenth-century inventory of mobile objects in the Palazzo, Moran situates the Lorenzetti instead in the Sala dei Nove. This double proposition strikes me as a desperate attempt at obfuscation for the sake of sustaining an attack on the traditional attribution of the Guidoriccio.

A commission for the representation of the Sienese state was contemplated in December 1424, but its terms could suggest a series of topographic views as easily as a map, and the place of display is unclear: "Deliberatum etiam quod pingantur sive designentur ad bazeum omnes terre acquisite et recuperate tempore present is regiminis in sala balistarum, sive in sala magna Consilii, prout alias per eos deliberabitur" (It was also deliberated that all lands acquired and retaken at the time of the present government be painted or represented at/on [?] in the Sala delle Balestre, or the great hall of the Council, accordingly others [other lands] as it will be deliberated by them).

Was this image of the Sienese state executed? In any event, it could not have replaced the Mappamondo from which Saint Bernardino recalled an image of Italy, a work still visible in 1427. Moreover, the inventory of mobile objects cited by Moran merely places the Mappamondo in a "sala delle balestre" of which there were two on the second floor. Given the explicit distinction Tizio makes between the room of the map's location and the Sala della Pace, Moran's interpretation of the ambiguously worded inventory seems gratuitous. Thus, despite Moran's and Mallory's objections, the scholarly consensus concerning the installation of the Mappamondo is not seriously challenged.

However, the material of the work's support has remained a matter of confusion. Many scholars have assumed that Lorenzetti's work of 1345 was painted either on panel or vellum. As a result, some have brushed aside della Valle's statement that the map was painted on cloth; others have pointed to his remark as an indication that the Lorenzetti was eventually replaced with a later work. Yet there is no good reason to doubt della Valle.

Given the size of Lorenzetti's map and the manner of its installation, a wood panel would have been impractical; a tondo of just under 16 feet (4.83 m) in diameter would have been far too heavy to rotate on a single pivot. Vellum, on the other hand, is nearly as light and perhaps even more durable than cloth, but would hardly have provided an elegant solution. To yield a surface the size and shape of Lorenzetti's map, numerous skins would have had to be stitched together and cut into a circle. Easily nine deer hides, about the size of the late thirteenth-century Hereford and Duchy of Cornwall maps (respectively 5 ft. 2 in. x 4 ft. 4 in. [1.58 x 1.30 m] and 5 ft. 5 in. [1.64 m] square), would have been required. Indeed, the giant Ebstorf map of around 1300 (11 ft. 9 in. [3.57 m] square) was painted on thirty goatskin panels sewn together. The necessarily patchwork quality of the resulting pictorial surface seems unlikely to have appealed aesthetically to Lorenzetti or his patrons. Moreover, how would vellum have been mounted on a rotating frame? Cloth, not vellum, could have been stretched over an open wooden framework necessary to minimize the weight of the artifact. The concentric rings scratched into the fresco beneath the map would seem logically to reflect either the construction of such a stretcher or perhaps a series of spaced rollers attached to the back of the framework. Rollers may have served to hold the frame parallel to the wall; otherwise, the wheel map, handled from below, could have been prone to tilting.

Furthermore, the use of doth as the support of choice for display maps is well documented. Around 1299-1300, a mappamundi painted on cloth was inventoried in the possession of King Edward I of England; of this lost object, nothing else is known. Fabric appears to have become an increasingly common support for cartographic images in the fifteenth century, and Rene of Anjou (1409-1480), king of Hungary, Jerusalem, Naples, and Sicily, had many such items. In 1493, the Sienese cardinal Francesco Todeschini Piccolomini gave to Siena Cathedral a circular map of the world painted on cloth ("Cosmographiam Ptolomei, quam Mappam Mundi appellant, lintea tela depictam . . . in forma rotunda"); it had originally been made in the early 1460s for Piccolomini's uncle Pope Pius II by the Venetian Antonio Leonardi. Might this commission have on some level played off the Mappamondo in the Palazzo Pubblico?

The disk silhouetted on the Guidoriccio wall conforms to the expected shape for the genre of image, a mappamundi or mappamondo, specified in the earliest references to Lorenzetti's work. Yet this structural coincidence between physical artifact and cartographic image already begins to reveal the remarkable character of the commission. In the medieval period, the representation of the world as circular rarely extended to the shape of the support. Such a correspondence between circular map image and an artifact's physical form occurs, for example, with metalwork tables recorded in the treasuries of secular rulers, but not usually in the case of wall maps. The few large vellum mappaemundi that survive from the thirteenth century, indicative of a widely disseminated tradition, adopt a quadrilateral format (the Hereford retains the neck of the hide) in which the circular image of the world is inscribed. One possible exception that springs to mind, however, is significant for what it suggests about the aims of the Lorenzetti commission. The lost mappamundi painted in 1239 for the great hall of Winchester Castle could well have been a circular object, for it was conceived in all likelihood as a pendant to a Wheel of Fortune installed three years earlier on the wall above the royal dais. |