Grotesques frescoes |

The word grotesque comes from the same Latin root as "grotto", which originated from Greek krypte "hidden place",[1] meaning a small cave or hollow. The original meaning was restricted to an extravagant style of Ancient Roman decorative art rediscovered and then copied in Rome at the end of the 15th century. The "caves" were in fact rooms and corridors of the Domus Aurea, the unfinished palace complex started by Nero after the Great Fire of Rome in AD 64, which had become overgrown and buried, until they were broken into again, mostly from above. Spreading from Italian to the other European languages, the term was long used largely interchangeably with arabesque and moresque for types of decorative patterns using curving foliage elements. History |

| Early examples in Roman ornamentsIn art, grotesques are ornamental arrangements of arabesques with interlaced garlands and small and fantastic human and animal figures, usually set out in a symmetrical pattern around some form of architectural framework, though this may be very flimsy. Such designs were fashionable in ancient Rome, as fresco wall decoration, floor mosaics, etc., and were decried by Vitruvius (c. 30 BC), who in dismissing them as meaningless and illogical, offered the description: "reeds are substituted for columns, fluted appendages with curly leaves and volutes take the place of pediments, candelabra support representations of shrines, and on top of their roofs grow slender stalks and volutes with human figures senselessly seated upon them." When Nero's Domus Aurea was inadvertently rediscovered in the late 15th century, buried in fifteen hundred years of fill, so that the rooms had the aspect of underground grottoes, the Roman wall decorations in fresco and delicate stucco were a revelation. |

||||

|

||||

|

||||

The painted decoration of the Domus Transitoria, Rome

|

||||

| The Domus Aurea, or Golden House, located between the Esquiline and Palatine Hills, was one of Nero's most extravagant projects. As everybody knows, two-thirds of the city of Rome were destroyed by a great fire in 64 AD. Nero used most of this land as a site for his new palace. It was not so much a palace as a series of buildings scattered over a landscaped "countryside" which included an artificial lake. The main building was extravagantly crafted, and boasted rooms and hallways decorated almost entirely in gold. In the case of the Domus, we know the names of the architects in charge of the project, Severus and Celer, and that of Fabullus, the painter who decorated many rooms.

|

||||

Domus Aurea Roma (4)

|

||||

|

||||

| The first appearance of the word grottesche appears in a contract of 1502 for the Piccolomini Library attached to the duomo of Siena. They were introduced by Raphael Sanzio and his team of decorative painters, who developed grottesche into a complete system of ornament in the Loggias that are part of the series of Raphael's Rooms in the Vatican Palace, Rome. "The decorations astonished and charmed a generation of artists that was familiar with the grammar of the classical orders but had not guessed till then that in their private houses the Romans had often disregarded those rules and had adopted instead a more fanciful and informal style that was all lightness, elegance and grace."[4] In these grotesque decorations a tablet or candelabrum might provide a focus; frames were extended into scrolls that formed part of the surrounding designs as a kind of scaffold, as Peter Ward-Jackson noted. Light scrolling grotesques could be ordered by confining them within the framing of a pilaster to give them more structure. Giovanni da Udine took up the theme of grotesques in decorating the Villa Madama, the most influential of the new Roman villas.

In the 16th century, such artistic license and irrationality was controversial matter. Francisco de Holanda puts a defense in the mouth of Michelangelo in his third dialogue of Da Pintura Antiga, 1548:

|

||||

Wall ornament by Raffael Vatican Museums

|

||||

| Mannerism |

||||

| The delight of Mannerist artists and their patrons in arcane iconographic programs available only to the erudite could be embodied in schemes of grottesche,[6] Andrea Alciato's Emblemata (1522) offered ready-made iconographic shorthand for vignettes. More familiar material for grotesques could be drawn from Ovid's Metamorphoses.[7]

The Vatican loggias, a loggia corridor space in the Apostolic Palace open to the elements on one side, were decorated around 1519 by Raphaels's large team of artists, with Giovanni da Udine the main hand involved. Because of the relative unimportance of the space, and a desire to copy the Domus Aurea style, no large paintings were used, and the surfaces were mostly covered with grotesque designs on a white background, with paintings imitating sculptures in niches, and small figurative subjects in a revival of Ancient Roman style. This large array provided a repertoire of elements that were the basis for later artists across Europe.[8] In Michelangelo's Medici Chapel Giovanni da Udine composed during 1532-33 "most beautiful sprays of foliage, rosettes and other ornaments in stucco and gold" in the coffers and "sprays of foliage, birds, masks and figures", with a result that did not please Pope Clement VII Medici, however, nor Giorgio Vasari, who whitewashed the grottesche decor in 1556.[9] Counter Reformation writers on the arts, notably Cardinal Gabriele Paleotti, bishop of Bologna,[10] turned upon grottesche with a righteous vengeance.[11] Vasari, echoing Vitruvius, described the style as follows:[12] "Grotesques are a type of extremely licentious and absurd painting done by the ancients ... without any logic, so that a weight is attached to a thin thread which could not support it, a horse is given legs made of leaves, a man has crane's legs, with countless other impossible absurdities; and the bizarrer the painter's imagination, the higher he was rated". Vasari recorded that Francesco Ubertini, called "Bacchiacca", delighted in inventing grotteschi, and (about 1545) painted for Duke Cosimo de' Medici a studiolo in a mezzanine at the Palazzo Vecchio "full of animals and rare plants".[13] Other 16th-century writers on grottesche included Daniele Barbaro, Pirro Ligorio and Gian Paolo Lomazzo.[14]

|

Grotesque engraving on paper, about 1500 - 1512, by Nicoletto da Modena Grotesque engraving on paper, about 1500 - 1512, by Nicoletto da Modena |

|||

In the meantime, through the medium of engravings the grotesque mode of surface ornament passed into the European artistic repertory of the 16th century, from Spain to Poland. A classic suite was that attributed to Enea Vico, published in 1540-41 under an evocative explanatory title, Leviores et extemporaneae picturae quas grotteschas vulgo vocant, "Light and extemporaneous pictures that are vulgarly called grotesques". Later Mannerist versions, especially in engraving, tended to lose that initial lightness and be much more densely filled than the airy well-spaced style used by the Romans and Raphael. Soon grottesche appeared in marquetry (fine woodwork), in maiolica produced above all at Urbino from the late 1520s, then in book illustration and in other decorative uses. At Fontainebleau Rosso Fiorentino and his team enriched the vocabulary of grotesques by combining them with the decorative form of strapwork, the portrayal of leather straps in plaster or wood moldings, which forms an element in grotesques. |

||||

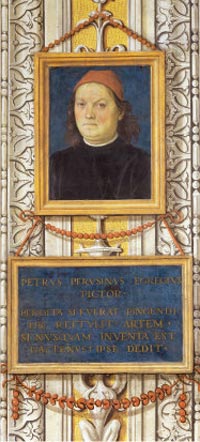

Pietro Perugino | Ornamentation of the Collegio del Cambio in Perugia |

||||

Perugino, Ceiling decoration (detail), 1497-1500, fresco, Collegio del Cambio, Perugia (3) r |

||||

| By the turn of the sixteenth century, some artists had begun to incorporate elements of grotesque decoration into their own, contemporary works. The earliest known examples are Perugino’s ceiling of the Cambio in Perugia (about 1500) and Pinturicchio’s cathedral library ceilings at Siena (1502). Other artists were likewsie inspired, among them Filippino Lippi, and Signorelli. Perhaps more importantly, the Chief Architect and Prefect of Antiquities at the Vatican, Raffaello Sanzio, studied and copied these designs, and directed that they be incorporated into the decorative schemes of the Vatican Loggia, the Loggetta of Cardinal Bibiena, and of the Loggia of Psyche at the Villa Farnesina. Much of the work on these projects was executed by Raphael’s assistants Giulio Romano, and Giovanni da Udine. Pietro Perugino Perugino was the greatest painter of the Umbrian school, active mainly in Perugia. He studied under Fiorenzo di Lorenzo, assisted Piero della Francesca at Arezzo, and in the early 1470s was a fellow pupil of Leonardo da Vinci and Lorenzo di Credi in Verrocchio's studio in Florence. From c. 1500 to c. 1504 Raphael was a pupil in his shop and may have helped with the fresco cycle in the Sala del Cambio at Perugia, Perugino's largest work in fresco. In the Sala di Udienza the Florentine woodcarver Domenico del Tasso (1440-1508) created the inlaid paneling and the richly carved "tribunal," or judges' bench in 1491-92. Perugino was commissioned for the fresco decoration in 1496, and the entire project was completed in 1500, the date that appears prominently on a painted tablet across from Perugino's self-portrait and signature. Because of its vaulted ceiling decorated with grotesques, the Sala di Udienza (Council Room) seems taller than it actually is. Its decor appears so consistent that one would not suspect that it was actually executed in several stages. The Florentine woodcarver Domenico del Tasso (1440-1508) created the inlaid paneling and the richly carved "tribunal," or judges' bench in 1491-92. The walls were decorated with frescoes by Perugino in 1497-1500.

|

||||

| Palazzo Chigi-Saracini in Siena |

||||

Siena, Palazzo Chigi Saracini cortile interno, affreschi di Giorgio di Giovanni [5]

|

||||

| Among the Medieval palazzi that line the elegant Via di Città in Siena, is the 14th century Palazzo Chigi-Saracini, currently the seat of the prestigious Accademia Musicale Chigiana founded in 1932. It has wonderfully complicated and beautifully decorated ceilings in the courtyard, painted by Giorgio di Giovanni.

The Palazzo was built by the Marescotti family in the 12th century. In 1506 it was purchased by Piccolomini-Mandoli who renovated its façade in a Renaissance style. In 1770 the house changed hands again and was purchased by the Saracini family who enlarged the façade in keeping with the line of the street and collected the works of art that adorn the interiors. It was the house of Count Galgano Lucarini Saracini and then it became property of Fabio Chigi Lucarini Saracini. The Count’s impressive art collection is still kept within the Accademia. The collection is particularly rich in Italian masters, particularly of the Senese School, such as Sassetta, Sodoma, Beccafumi, Botticelli.

|

||||

From Baroque to Victorian era |

||||

In the 17th and 18th centuries the grotesque encompasses a wide field of teratology (science of monsters) and artistic experimentation. The monstrous, for instance, often occurs as the notion of play. The sportiveness of the grotesque category can be seen in the notion of the preternatural category of the lusus naturae, in natural history writings and in cabinets of curiosities.[13][14] The last vestiges of romance, such as the marvellous also provide opportunities for the presentation of the grotesque in, for instance, operatic spectacle. The mixed form of the novel was commonly described as grotesque - see for instance Fielding's "comic epic poem in prose." (Joseph Andrews and Tom Jones) Artists began to give the tiny faces of the figures in grotesque decorations strange caricatured expressions, in a direct continuation of the medieval traditions of the drolleries in the border decorations or initials in illuminated manuscripts. From this the term began to be applied to larger caricatures, such as those of Leonardo da Vinci, and the modern sense began to develop. It is first recorded in English in 1646 from Sir Thomas Browne:"In nature there are no grotesques".[15] By extension backwards in time, the term became also used for the medieval originals, and in modern terminology medieval drolleries, half-human thumbnail vignettes drawn in the margins, and carved figures on buildings (that are not also waterspouts, and so gargoyles) are also called "grotesques".

|

||||

Images

Text

Bibliography

Further reading

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Podere Santa Pia, holiday house in the Tuscan Maremma

|

Podere Santa Pia |

Podere Santa Pia, view from the garden on the valley below |

||

|

||||

| Villa Lante, Bagnaia | Il parco dei Mostri di Bomarzo |

Villa I Tatti

|

||

|

||||

Villa Arceno gardens |

Abbey of Sant 'Antimo |

Villa La Pietra, near Florence |

||

This article incorporates material from the Wikipedia article Grotesque, published under the GNU Free Documentation License. |

||||