|

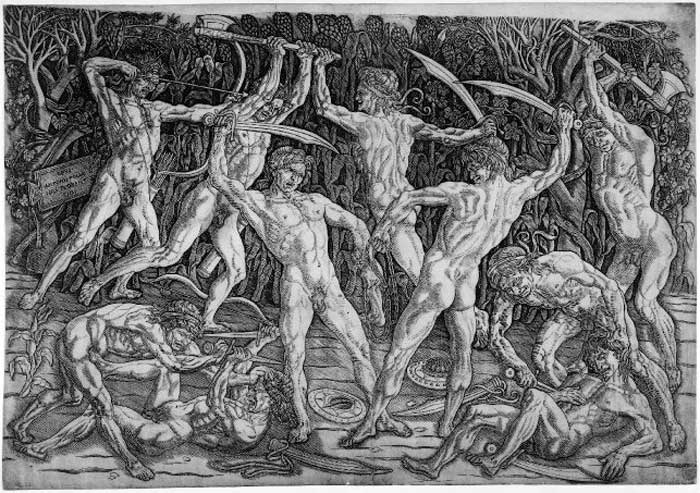

| Antonio del Pollaiuolo, Battle of the Nudes, 1465–1475. Engraving 42.4 x 60.9 cm. Second-state impression at the British Museum |

Battle of the Nudes |

| The Battle of the Nudes or Battle of the Naked Men,[1] probably dating from 1465–1475, is an engraving by the Florentine goldsmith and sculptor Antonio del Pollaiuolo which is one of the most significant old master prints of the Italian Renaissance. The engraving is large at 42.4 x 60.9 cm, and depicts five men wearing headbands and five men without, fighting in pairs with weapons in front of a dense background of vegetation. All the figures are posed in different strained and athletic positions, and the print is advanced for the period in this respect. The style is classicizing, although they grimace fiercely, and their musculature is strongly emphasized. An effective and largely original return-stroke engraving technique was employed to model the bodies, with delicate and subtle effect. The print clearly relates to the work of Mantegna, although uncertainty about the dating of the works of both artists means that the direction of influence is unclear. Mantegna made two large engravings of the "Battle of the Sea-Gods", and he or his followers produced a number of others of male nudes fighting under various classical titles. Despite the usual attempts by art historians, including in this case Erwin Panofsky, to identify a specific subject for the engraving, it is likely none was intended.[6] The two central figures grasp the ends of a large chain, which may suggest that the figures are to be seen as gladiators.[7] Vasari wrote of Pollaiuolo: He had a more modern grasp of the nude than the masters who preceded him, and he dissected many bodies to study their anatomy; and he was the first to demonstrate the method of searching out the muscles, in order that they might have their due form and place in his figures; and of those ... he engraved a battle. On the other hand, it has been suggested that Leonardo da Vinci may have had Pollaiuolo partly in mind when he wrote that artists should not: make their nudes wooden and without grace, so that they seem to look like a sack of nuts rather than the surface of a human being, or indeed a bundle of radishes rather than muscular nudes[8] Like all successful Renaissance prints, the Battle was copied by other printmakers, including "Johannes of Frankfurt" in about 1490.[9] States The existence of the first state was only realized in 1967, after Cleveland bought their print from the Liechtenstein collection. The best impression of the second state is in the Fogg Art Museum at Harvard; it appears to be the only one printed before the plate received a scratch, and from the paper and watermark would appear to have been printed close in time to the Cleveland impression.[13] The two woodcut copies can be shown to have been copied from the first state.[14] Date

|

|

||

Antonio del Pollaiuolo, Battle of the Nudes, 1465–1475. Engraving 42.4 x 60.9 cm. Second-state impression at the British Museum

|

||

| Pollaiuolo (1432-98) was a goldsmith and sculptor, and may have modelled his figures in clay or wax before drawing them. The two central nudes correspond to one single figure, seen from the front and back. This technique, which is characteristic of Pollaiuolo, is evident in The Martyrdom of St Sebastian (National Gallery, London). He signed this print with an impressive Latin inscription in the left background. Pollaiuolo and Mantegna were the first great Italian artists to make engravings, and each must have been aware of the other's work.[17] | ||

|

||

The 'Battle of the Nudes' exists in two states; although numerous impressions are known (approximately fifty), all but one are of the second state, printed after the plate had begun to wear out. The only example of the first state that has survived is in the Cleveland Museum of Art (formerly in the Liechtenstein Collection) and it shows the plate as it was originally engraved by the artist (see S.R. Langdale, exh. cat., The Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, 'Battle of the Nudes. Pollaiuolo's Renaissance Masterpiece', 2002). The earliest surviving example printed from the reworked plate is in the Fogg Art Museum (Harvard University). Most of the second-state impressions were trimmed, the edge of the sheets creased, abrased, soiled or torn and the areas that did not print well or suffered damage over the years often redrawn in pen and ink (a useful list of some of these is given by Langdale pp. 72-82) . |

||||

|

This article incorporates material from the Wikipedia article Battle of the Nudes (engraving) published under the GNU Free Documentation License.

|

||||

|

||||

Podere Santa Pia |

Podere Santa Pia, garden view, April |

View from terrace with a stunning view over the Maremma and Montecristo |

||

|

||||

The abbey of Sant'Antimo |

Cortona |

Spoleto, Duomo |

||

|

||||

Crete Senesi, surroundings of Podere Santa Pia |

Val d'Orcia" tra Montalcino Pienza e San Quirico d’Orcia. |

Massa Marittima |

||