| |

|

Storia

Lo stato degli affreschi è buono, tranne nelle parti dove era steso un pigmento blu scuro, che è andato via rivelando il sottostante strato bianco, con l'effetto che le parti in ombra delle vesti risultano oggi più chiare.

Filippo Carducci fece decorare ad Andrea del Castagno la loggia della villa, che successivamente venne trasformata in salone. Il ciclo è il più antico esempio pervenutoci di celebrazione degli uomini illustri in chiave profana, civile e umanistica, dove veniva sottolineato il valore delle virtù morali degli uomini, che venivano innalzati a una dimensione eroica. Se fino ad allora i personaggi erano spesso tratti dalla Bibbia e dalla mitologia, quindi modelli astratti e fuori dal tempo; nel ciclo di Legnaia, a parte le figure femminili, vennero scelti personaggi del passato prossimo di Firenze, ancora vivi nella memoria. Questa particolare iconografia si ispirò a Boccaccio, ma anche a Plutarco, il cui De virtibus mulieribus era stato tradotto dal latino entro il 1495 da Alamanno Rinuccini, cugino di Andrea Carducci e nipote di Filippo.

Gli affreschi sono descritti nel Memoriale di Francesco Albertini del 1510.

Il ciclo venne coperto da intonaco bianco in epoca imprecisata e fu riscoperto nel 1847, quando il Granduca acquistò gli affreschi e li fece staccare. Dopo essere stati esposti nel Museo del Bargello dal 1865, i pannelli staccati furono trasferiti nel museo di Andrea del Castagno nel Cenacolo di Sant'Apollonia, dove in seguito all'alluvione di Firenze del 1966 vennero di nuovo rimossi, per approdare agli Uffizi nel 1969, dove vennero collocati nella ex-chiesa di San Pier Scheraggio. La sala della ex-chiesa è per adesso visitabile solo su appuntamento.

Nel frattempo, nel 1948-1949, alcuni saggi rivelarono la presenza nella villa di altri affreschi, che vennero in seguito rinvenuti: si tratta proprio della Madonna col Bambino con angeli reggicortina e dell'Adamo ed Eva che si trovano in situ.

Descrizione

Il ciclo è composto da affreschi che si dispongono a gruppi di tre su ciascuna parete, più la parete centrale dove si apriva la porta, decorata dalla vaporosa tenda dove si trovano la Madonna col Bambino, gli Angeli reggicortina, Adamo ed Eva. In alto, la fascia con putti, festoni e stemmi araldici, risale al 1472.

La prima parete è occupata da personaggi che si distinsero nella politica, dentro e fuori Firenze:

Pippo Spano, condottiero in Ungheria, combatté contro gli Ottomani a fianco del re ungherese guadagnando fama e onori (ispan, che è il suo soprannome, significa proprio conte in ungherese)

Farinata degli Uberti, capo dei ghibellini fiorentini

Niccolò Acciaiuoli, gran siniscalco del Re di Napoli

La seconda è dedicata alle donne:

la Sibilla Cumana, che veniva assimilata ai profeti dell'Antico Testamento

la Regina Ester, che incontrò il re Assuero per proteggere il popolo ebraico

la Regina Tomiri, capo del popolo nomade dei Massageti, per vendicare la morte del figlio scatenò la battaglia dove Ciro il Grande trovò la morte (la figura fu danneggiata dall'apertura di una porta nella parete)

La terza è dedicata ai letterati fiorentini:

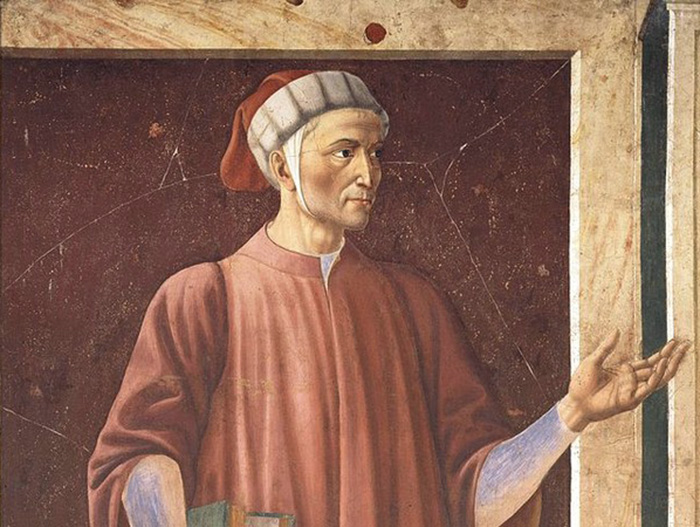

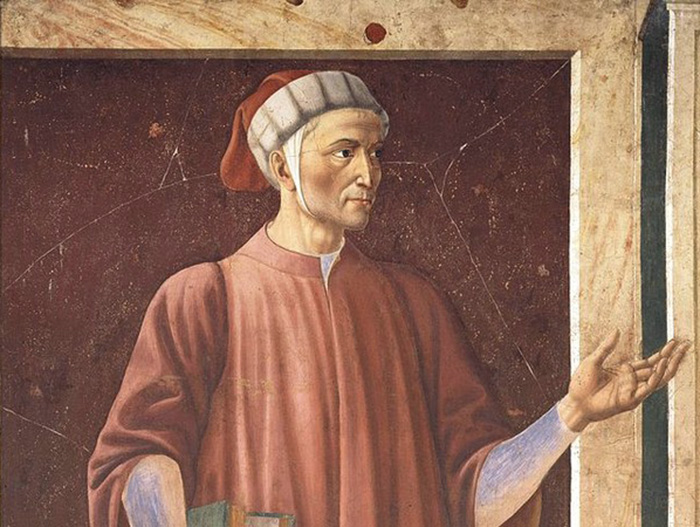

Dante Alighieri

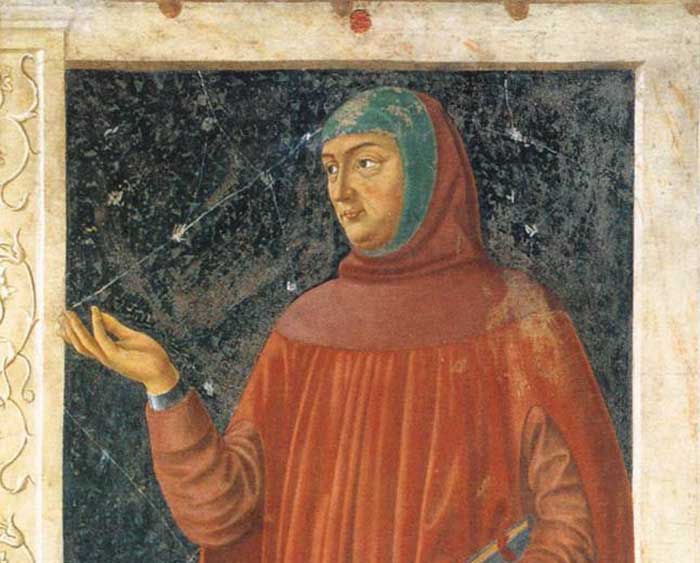

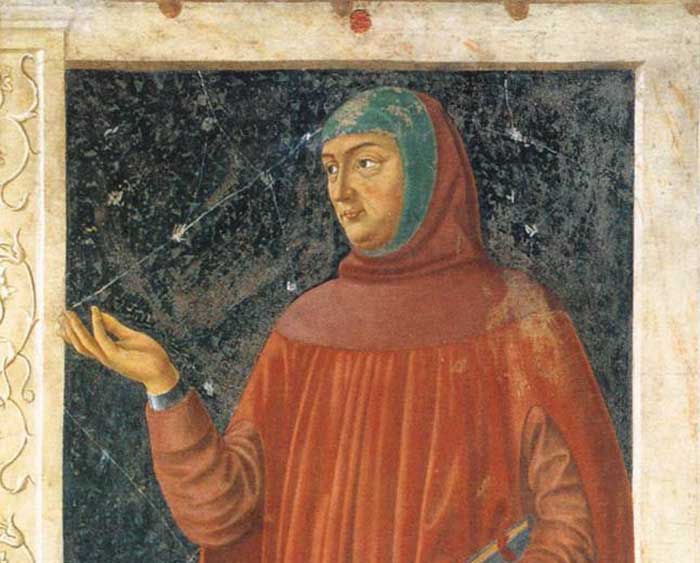

Francesco Petrarca

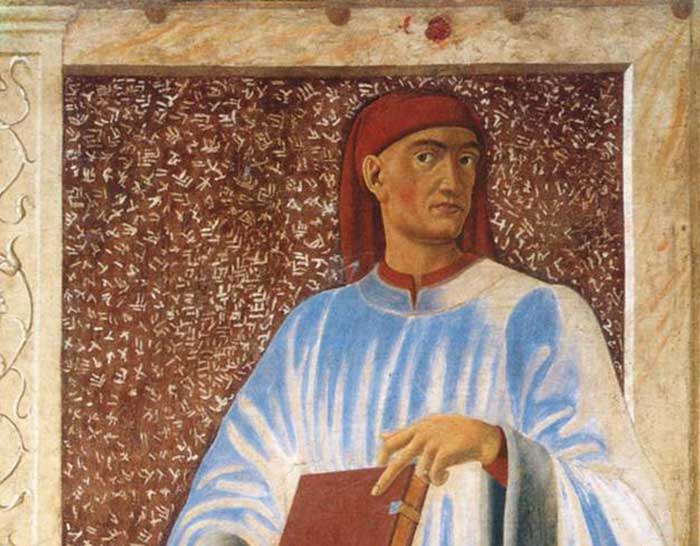

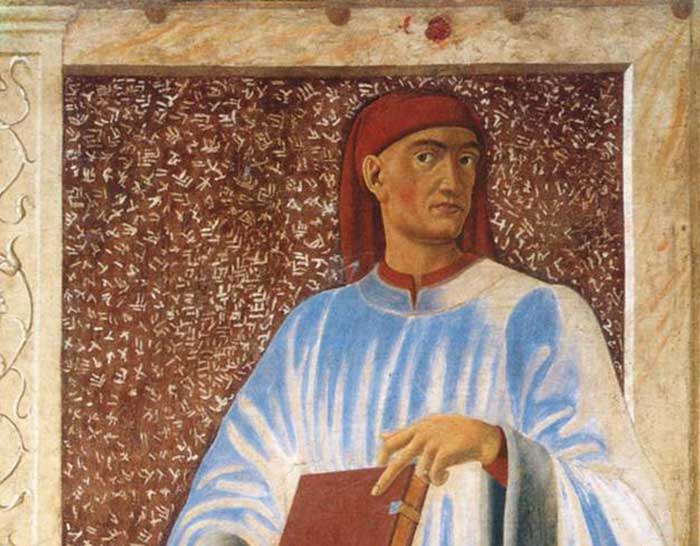

Giovanni Boccaccio

|

|

Madonna and Child, c. 1450, fresco, Villa Carducci, Soffiano (Florence)

|

Le figure sono rappresentate come statue in posizione eroica, in nicchie rettangolari dipinte con lo sfondo di un pannello di finto marmo. Ciascuna emerge con un punto di vista ribassato, ed è dotata di notevole monumentalità, data dal chiaroscuro e dagli effetti di scorcio, soprattutto nello zoccolo marmoreo alla base delle figure, dove a volte un piede si proietta verso l'esterno, "invadendo" lo spazio dello spettatore.

La figura di Pippo Spano, una delle più originali, è composta entro uno schema di due triangoli uguali sovrapposti, composti dalle braccia con la spada orizzontale e dalle gambe divaricate con la base. Come nel San Giorgio di Donatello, del 1417, le gambe divaricate sono un modo per far risaltare, con il torso ben eretto, l'idea di fermezza morale. La leggera torsione del busto, pure ripresa da Donatello, anima la figura che non appare schematicamente rigida, ma anzi sembra alludere a un movimento in potenza pronto a scattare da un momento all'altro: questa idea di movimento impellente si trasmette allo spettatore attraverso una linea di contorno "energetica" e dinamica, come teorizzò Roberto Longhi.

|

|

Andrea del Castagno, Dante Alighieri

|

Andrea del Castagno (or Andrea di Bartolo di Bargilla) (c. 1421–1457) was an Italian painter from Florence, influenced chiefly by Tommaso Masaccio and Giotto di Bondone. His works include frescoes in Sant'Apollonia in Florence and the painted equestrian monument of Niccolò da Tolentino (1456) in the Cathedral in Florence. Little is known about his formation, though it has been hypothised that he apprenticed under Fra Filippo Lippi and Paolo Uccello. One of his earliest works depicts those hung after the Battle of Anghiari of the Florentine war with Milan. Castagno painted this after returning home to Castagno, outside Florence after the war around 1440, and the work appears on the façade of the Palazzo del Podestá. In 1447 he worked in the refectory of Sant'Apollonia in Florence, painting, in the lower part, Last Supper fresco, [2] accompanied by other scenes portraying the Deposition, Resurrection, [3] and Crucifixion, which are now damaged. In 1449-1450 he painted the Assumption with Saints Julian and Miniato for the church of San Miniato fra le Torri (now in Berlin). In the same years he collaborated with Filippo Carducci to the series of Illustrious People for the Villa Carducci at Legnaia.

Andrea del Castagno died of the plague in Florence on Aug. 19, 1457. |

|

Andrea del Castagno, Dante Alighieri, from the Cycle of Famous Men and Women, c. 1450. Detached fresco. 247 x 153 cm. Galleria degli Uffizi, Firenze. The picture shows one of the three Tuscan poets represented in the cycle.

|

|

|

Francesco Petrarca (1304 – 1374), commonly anglicized as Petrarch, was an Italian scholar and poet in Renaissance Italy, and one of the earliest humanists. Petrarch's rediscovery of Cicero's letters is often credited for initiating the 14th-century Renaissance. In the 16th century, Pietro Bembo created the model for the modern Italian language based on Petrarch's works, as well as those of Giovanni Boccaccio, and, to a lesser extent, Dante Alighieri.[3] Petrarch would be later endorsed as a model for Italian style by the Accademia della Crusca. Petrarch's sonnets were admired and imitated throughout Europe during the Renaissance and became a model for lyrical poetry. He is also known for being the first to develop the concept of the "Dark Ages".[4]

Petrarch was born Francesco Petrarca on July 20, 1304, in Arezzo, Tuscany. He was a devoted classical scholar who is considered the "Father of Humanism," a philosophy that helped spark the Renaissance. Petrarch's writing includes well-known odes to Laura, his idealized love.

His writing was also used to shape the modern Italian language. Petrarch is best known for his Italian poetry, notably the Canzoniere ("Songbook") and the Trionfi ("Triumphs").

Influenced by his interest in the classics, many of Petrarch’s poems are highly allegorical and constructed using Italian forms such as terza rima, ballate, sestine and canzoni. His poems investigate the connection between love and chastity in the foreground of a political landscape, though many of them are also driven by emotion and sentimentality. Critic Robert Stanley Martin writes that Petrarch “reimagined the conventions of love poetry in the most profound way: love for the idealized lady was the path towards learning how to properly love God . . . His work has a grace that, among his predecessors, is second only to Dante’s, and it often shows a greater refinement, particularly in its development of conceits. Petrarch will often begin with a single trope and develop it into a conceit that defines the entire sonnet.”

He died at age 69 on July 18 or 19, 1374, in Arquà, Carrara.

|

|

|

|

|

The picture depicts Boccaccio, one of the three Tuscan poets represented in the cycle.

Giovanni Boccaccio (1313-1375), was an Italian poet and scholar, best remembered as the author of the earthy tales in the Decameron. With Petrarch he laid the foundations for the humanism of the Renaissance and raised vernacular literature to the level and status of the classics of antiquity.

Boccaccio wrote a number of notable works, including the Decameron and On Famous Women. As a poet who wrote in the Italian vernacular, Boccaccio is particularly noted for his realistic dialogue, which differed from that of his contemporaries, medieval writers who usually followed formulaic models for character and plot.

Boccaccio grew up in Florence. His father worked for the Compagnia dei Bardi and in the 1320s married Margherita dei Mardoli, of well-to-do family.

His father introduced him to the Neapolitan nobility and the French-influenced court of Robert the Wise (the king of Naples) in the 1330s. At this time he fell in love with a married daughter of the king, who is portrayed as "Fiammetta" in many of Boccaccio's prose romances, including Il Filocolo (1338). Boccaccio became a friend of fellow Florentine Niccolò Acciaioli, and benefited from his influence as the administrator, and perhaps the lover, of Catherine of Valois-Courtenay, widow of Philip I of Taranto. Acciaioli later became counselor to Queen Joan I of Naples and, eventually, her Grand Seneschal.

In Naples, Boccaccio began what he considered his true vocation, poetry. Works produced in this period include Filostrato and Teseida (the sources for Chaucer's Troilus and Criseyde and The Knight's Tale, respectively), Filocolo, a prose version of an existing French romance, and La caccia di Diana, a poem in terza rima listing Neapolitan women.[7] The period featured considerable formal innovation, including possibly the introduction of the Sicilian octave to Florence, where it influenced Petrarch.

Boccaccio began work on the Decameron[9][10] around 1349. It is probable that the structures of many of the tales date from earlier in his career, but the choice of a hundred tales and the frame-story lieta brigata of three men and seven women dates from this time. The work was largely complete by 1352. It was Boccaccio's final effort in literature and one of his last works in Italian; the only other substantial work was Corbaccio (dated to either 1355 or 1365). Boccaccio revised and rewrote the Decameron in 1370–1371. This manuscript has survived to the present day.

In 1360, Boccaccio began work on De mulieribus claris, a book offering biographies of one hundred and six famous women, that he completed in 1374.

Following the failed coup of 1361, a number of Boccaccio's close friends and other acquaintances were executed or exiled in the subsequent purge. Although not directly linked to the conspiracy, it was in this year that Boccaccio left Florence to reside in Certaldo, and became less involved in government affairs. He did not undertake further missions for Florence until 1365, and traveled to Naples and then on to Padua and Venice, where he met up with Petrarch in grand style at Palazzo Molina, Petrarch's residence as well as the place of Petrarch's library. He later returned to Certaldo. He met Petrarch only once again, in Padua in 1368. Upon hearing of the death of Petrarch (19 July 1374), Boccaccio wrote a commemorative poem, including it in his collection of lyric poems, the Rime.

Boccaccio's change in writing style in the 1350s was not due just to meeting with Petrarch. It was mostly due to poor health and a premature weakening of his physical strength. It also was due to disappointments in love. Some such disappointment could explain why Boccaccio, having previously written always in praise of women and love, came suddenly to write in a bitter Corbaccio style. Petrarch describes how Pietro Petrone (a Carthusian monk) on his death bed in 1362 sent another Carthusian (Gioacchino Ciani) to urge him to renounce his worldly studies.[16] Petrarch then dissuaded Boccaccio from burning his own works and selling off his personal library, letters, books, and manuscripts. Petrarch even offered to purchase Boccaccio's library, so that it would become part of Petrarch's library. However, upon Boccaccio's death his entire collection was given to the monastery of Santo Spirito, in Florence, where it still resides.[17]

His final years were troubled by illnesses, some relating to obesity and what often is described as dropsy, severe edema that would be described today as congestive heart failure. He died at the age of sixty-two on 21 December 1375 in Certaldo, where he is buried.

|

|

|

| The picture shows one of the three famous women represented in the cycle.

Esther, the beautiful Jewish wife of the Persian king Ahasuerus (Xerxes I), and her cousin Mordecai persuaded the king to retract an order for the general annihilation of Jews throughout the empire. The massacre had been plotted by the king's chief minister, Haman, and the date decided by casting lots (purim). Instead, Haman was hanged on the gallows he built for Mordecai; and on the day planned for their annihilation, the Jews destroyed their enemies. |

|

Famous Persons: Queen Esther, c. 1450, fresco transferred to wood, 120 x 150 cm, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence |

| |

|

The Cumaean Sibyl is one of the three famous women represented in the cycle.

The Cumaean Sibyl, wrapped in a wide red cloak with metallic highlights on the folds, also represents the same heroic ideals as the commanders. The severity of her face, which is both beautiful and dignified, together with her raised right hand, is the sign of the gravity of her prophecies.

A famous collection of sibylline prophecies, the Sibylline Books, was traditionally offered for sale to Tarquinius Superbus, the last of the seven kings of Rome, by the Cumaean sibyl. He refused to pay her price, so the sibyl burned six of the books before finally selling him the remaining three at the price she had originally asked for all nine. The books were thereafter kept in the temple of Jupiter on the Capitoline Hill, to be consulted only in emergencies.

The Cumaean Sibyl was the priestess presiding over the Apollonian oracle at Cumae, a Greek colony located near Naples, Italy. The word sibyl comes (via Latin) from the ancient Greek word sibylla, meaning prophetess. There were many sibyls in different locations throughout the ancient world. The importance of the Cumaean Sibyl in the legends of early Rome as codified in Virgil's Aeneid VI, the Cumaean Sibyl became the most famous among the Romans, because she was near to Roma. The Erythraean Sibyl from modern-day Turkey was famed among Greeks, as was the oldest Hellenic oracle, Sibyl of Dodona, possibly dating to the second millennium BC according to Herodotus favored in the east.

The Cumaean Sibyl is one of the four sibyls painted by Raphael at Santa Maria della Pace (see gallery below.) She was also painted by Andrea del Castagno (Uffizi Gallery, illustration right), and in the Sistine Ceiling of Michelangelo her powerful presence overshadows every other sibyl, even her younger and more beautiful sisters, such as the Delphic Sibyl.

There are various names for the Cumaean Sibyl besides the "Herophile" of Pausanias and Lactantius[5] or the Aeneid's "Deiphobe, daughter of Glaucus": "Amaltheia", "Demophile" or "Taraxandra" are all offered in various references.

Stories recounted in Virgil's Æneid

The Cumaean Sibyl prophesied by “singing the fates” and writing on oak leaves. These would be arranged inside the entrance of her cave but, if the wind blew and scattered them, she would not help to reassemble the leaves to form the original prophecy again.

The Sibyl was a guide to the underworld (Hades), its entry being at the nearby crater of Avernus. Aeneas employed her services before his descent to the lower world to visit his dead father Anchises, but she warned him that it was no light undertaking:

Trojan, Anchises' son, the descent of Avernus is easy.

All night long, all day, the doors of Hades stand open.

But to retrace the path, to come up to the sweet air of heaven,

That is labour indeed. (Aeneid 6.126-129.)

Stories recounted in Ovid's Metamorphoses

Although she was a mortal, the Sibyl lived about a thousand years. This came about when Apollo offered to grant her a wish in exchange for her virginity; she took a handful of sand and asked to live for as many years as the grains of sand she held. Later, after she refused the god's love, he allowed her body to wither away because she failed to ask for eternal youth. Her body grew smaller with age and eventually was kept in a jar (ampulla). Eventually only her voice was left (Metamorphoses 14; compare the myth of Tithonus).[6]

|

|

|

|

Niccolò was statesman, soldier, and grand seneschal of Naples who enjoyed a predominant position in the Neapolitan court. He led the conquest of almost all of Sicily (1356-57).

|

The picture shows Niccolò Acciaioli, one of the three Florentine military commanders represented in the cycle.

Niccolò Acciaioli (1310-1365) was an Italian noble, a member of the Florentine banking family of the Acciaioli. He was the grand seneschal of the Kingdom of Naples and count of Melfi, Malta, and Gozo in the mid-fourteenth century. Of a prominent and wealthy Florentine family, Acciaiuoli went to Naples in 1331 to direct the family’s banking interests. In 1335 King Robert made him a knight, entrusted him with the care of his nephew Louis of Taranto, and bestowed upon him a series of fiefs in Apulia and in Greece.

He was a friend of writers and humanists , including Petrarch and Boccaccio. |

|

Famous Persons: Niccolò Acciaioli, c. 1450, fresco transferred to wood, 120 x 150 cm, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence

|

|

|

The picture shows Pippo Spano, one of the three Florentine military commanders represented in the cycle.

One of the most successful portrayals is the figure of Pippo Spano, a famous Florentine conottiero (who died in Hungary in 1426), seen as the ideal hero. The masterful draughtsmanship and the perceptive description of the character, shown in a natural pose, confirm the opinion Vasari expressed of Andrea's work: "He was extremely talented at portraying figures in solemn poses and in making them awesome, both men and women, with fierce expressions created thanks to his excellent draughtsmanship." |

|

Famous Persons: Pippo Spano, c. 1450, fresco transferred to wood, 120 x 150 cm, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence

|

|

Andrea del Castagno, Famous Persons: Farinata degli Uberti, c. 1450, fresco transferred to wood, 250 x 154 cm, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence

|

| |

|

|

The picture shows one of the three Florentine military commanders represented in the cycle, Farinata degli Uberti.

Farinata degli Uberti (... – November 11, 1264), real name Manente degli Uberti,[1] was an Italian aristocrat and military leader, considered by some of his contemporaries to be a heretic. He is remembered mostly for his appearance in Dante Alighieri's Inferno and is mentioned in C.S. Lewis's short "sequel" to The Screwtape Letters, Screwtape Proposes a Toast.

Farinata degli Uberti was a Florentine nobleman who became the leader of the Florentine Ghibellines, the proimperial party. According to Dante, Uberti alone dissuaded the members of the Ghibelline coalition from razing the city of Florence, which they had just captured.

Life

Farinata belonged to one of the most ancient and prominent noble families of Florence. He was the leader of the Ghibelline faction in his city during the power struggles of the time. He led the Ghibellines from 1239, but after the death of the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II, in 1250, the Guelphs were able to reassert power in Florence, securing his exile from the city, along with his supporters. The exiles sought refuge in Siena, a Ghibelline stronghold. In response to the exile, Farinata allied himself with Frederick's illegitimate son, Manfred of Sicily, who was seeking to expand his alliances in order to secure himself on the throne of Sicily. In September 1260 Farinata led the Ghibelline forces to victory over the rival Guelphs at the Battle of Montaperti. As a result he was able to capture Florence. The leading Guelph families were banished and the government of Florence was radically restructured to ensure Ghibelline dominance.

Farinata's allies wanted to ensure that Florence would never again rise to threaten them. Following the example of Roman ruthlessness towards its enemy Carthage, they voted to raze Florence utterly to the ground. Only Farinata stood out against them, declaring himself to be a Florentine first and a Ghibelline second, and vowing that he would defend his native city with his own sword. The Ghibellines thereupon took the lesser course of destroying the city's defences and the homes of the leading Guelphs, knocking down 103 palaces, 580 houses, and 85 towers.

When the Guelphs regained control of the city in 1266, they repeated in reverse the demolitions, by destroying every building belonging to the Uberti clan, which were in what is now Piazza della Signoria, decreeing as well that no building should ever be erected in that accursed space. This is why Palazzo Vecchio, begun in the 1290s, is not in the center of the piazza, as one might expect, but squeezed over to one side.

Heresy

|

|

Andrea del Castagno, Famous Persons: Farinata degli Uberti, c. 1450, fresco transferred to wood, 250 x 154 cm, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence Andrea del Castagno, Famous Persons: Farinata degli Uberti, c. 1450, fresco transferred to wood, 250 x 154 cm, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence |

Farinata died at Florence in 1264. In 1283 his body and his wife's, Adaleta, were exhumed from their resting place in Santa Reparata; and subsequently tried for heresy. They were proven guilty by the Franciscan-led inquisition; their remains faced a posthumous execution. According to Boccaccio, in his commentary on Dante, the inquisition discovered, among other things, that Farinata denied life after death:

He was of the opinion of Epicurus, that the soul dies with the body, and maintained that human happiness consisted in temporal pleasures; but he did not follow these in the way that Epicurus did, that is by making long fasts to have afterwards pleasure in eating dry bread; but was fond of good and delicate viands, and ate them without waiting to be hungry; and for this sin he is damned as a Heretic in this place.

Therefore, Farinata appears with several other atheists and heretics in Dante's Inferno. Since they denied the immortality of the soul, their eternal punishment is to be entombed in fiery coffins, de ads among the deads, within the city of Dis.

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Cenacolo of Sant’Apollonia with the Famous Men and Women by Andrea del Castagno, photograph from the beginning of the nineteenth century, when the fresco cycle was transferred toSant'Apollonia, Florence

|

|

|

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()