[1] Local legend has it that Monterchi, or 'Mount Hercules', was where Hercules performed one of his labours. In pagan times, Monterchi was associated with a fertility cult, the Catholic church was very good at absorbing pagan festivals and rituals into its belief system so it likely that the area still had associations with fertility. Piero della Francesca grew up in nearby Sansepolcro but his mother was from Monterchi. These factors must have made it seem an appropriate place for Piero to paint a heavily pregnant Madonna.

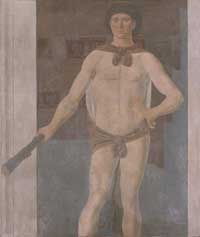

This fresco once adorned Piero della Francesca’s house in Borgo Sansepolcro. The painting was originally positioned in the upper corner of a room, with its right edge bordering a wall, which helps explain the steep perspective of the image. Hercules stands at a threshold. Beyond, we can see a ceiling with wooden beams decorated with foliage. There is no evidence that the room was decorated with other gods or heroes, as might be expected. Further, Piero della Francesco chose to portray Hercules as a youth, rather than as the bearded, muscle-bound figure familiar in ancient sculpture. Certainly the ideal nude was a central theme of the Italian Renaissance. However, it remains a mystery what this image of the young Hercules might signify in the painter’s private dwelling, although the hero was commonly associated with civic virtue and goodness. Perhaps the painting of a classical nude in unusually steep perspective was a compelling artistic challenge for Piero.

Mrs. Gardner’s attempt to acquire the fresco was also Herculean. The fresco had been detached from the wall in the 1860s and in 1903 it was sold to Gardner by the Florentine dealer Elia Volpi, with the assistance of Joseph Lindon Smith. However, the Italian government delayed the work’s export until 1908, and when it arrived in America, it was seized by customs officials for payment of duty and fines. At Fenway Court, it became the centerpiece of a new gallery of early Italian pictures where it was displayed in front of a flame-stitched embroidery.

Source: Alan Chong, "Hercules," in Eye of the Beholder, edited by Alan Chong et al. (Boston: ISGM and Beacon Press, 2003): 53

[2] Alan Chong, Curator of the Collection | Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum

[3] The action of carbon dioxide on hydrated lime is the secret to the success of the fresco method of wall painting. The Italian word 'fresco' merely means fresh (plaster), if pigments are applied to fresh damp plaster then the colours will be bound to the plaster by the formation of calcium carbonate, this binding can only take place while the plaster is damp and carbon dioxide is able to react with the hydrated lime. Once the pigments are bound to the plaster they will retain much of their brilliance, even for thousands of years, as the surviving painting shows.

[4] Acquired by the museum in 1908. It was discovered in I 860-70 on a wall of the house on Via deIle Aggiunte which fro 1465 belonged to the family of Piero della Francesca, which had in all likelihood previously belonged to the Graziani. It is a fragment, missing an upper strip and an area at the bottom large enough to complete the figure's legs.

The fresco's original place on the wall has not been identified. The hero appears to be framed by the jambs of a door and stands on the threshold, on the spectator's side of the room he is entering, as indicated by the club and the index finger of the hand holding it, which overlap the door frame. The light of the room pervades the youthful body, giving rise to a continual reflection that hems in the parts which are not illuminated. Light establishes the magical relationship between the space excluded from the picture (the space of the onlooker) and the apparition of the god. Behind him one can see the halflit wall of another room, with three brackets supporting beams decorated with a motif of grey palms (or rather silver, but halflit) on a red background.

Hercules is not seen from below looking up, which we would expect were the picture placed above us, but this fact does not allow us to establish its height from the floor of the actual room. Certainly it was not placed at the height of the guests in the room, as the steep perspective of

the beams indicates a very high ceiling seen from a fairly acute angle, as if

the spectator finds himself looking immediately above him at the room which the hero has just left. The image hovers against the unknown and dark world of the nonexistent room, whose height or depth cannot be understood. The brackets which support the beams have no sides, and the designs on the sides of the ornate beams suggest a kind of surface marquetry. Piero is extraordinarily aware of the decorative character of the fresco and demonstrates here his experience as creator of marquetry designs. The pure white of the door-jamb against which the hand with the club is profiled, establishes (as in the Rimini chapel) a relationship with the light of the real room and moves the imaginary space into another dimension.

It is difficult to believe that this work, which seems self contained, was the beginning of an incomplete decoration, as Salmi (1979) believed. It would have been a succession of recessed and projecting wall sections, and unlikely anticipation of Bramante's ideas.

The fresco, which sustained serious damage in the operation of removal and possibly during transport, is, along with the Urbino diptych, aIl that remains of Piero's non-Christian subjects. Piero chose to portray the god as young and beardless. The body does not display enlarged muscles and the delicate relief of the breastbone and the pectorals, with the light indentation of the navel, recall fragments of ancient torsoes, even if perhaps known only in Roman copies. The young hero had already appeared on the jambs of the Porta della Mandorla in Florence cathedral, almost coincidentally with publication of the De laboribus Herculis by Coluccio Salutati. The face, framed by black curls, has a pure and preoccupied expression almost like a sacred image; only the lips express something like disappointment or sulkiness: the controlled severity of a god capable of being terrifying. Hercules has already completed his first task, killing the Nemean lion. His appearance on the threshold, with his resolute gesture and distant gaze demonstrate bis determination. At the same time his naked body is seen with greater frankness than the Christ in the Baptism or in the Resurrection, while portrayed with a freer hand that the Arezzo Adamites.

Inside the rectangle of the door, the figure is constructed by means of contrasting straight and oblique lines where the right hand would create the vertex of an ideal triangle from the architrave and the threshold.

If Piero had painted the fresco when Antonio del Pollaiuolo had already begun dealing with the myth of Hercules (1460), the contrast bet ween the two opposed visions could not be not be better exemplified. The date of 1465, when the house was bought by the Franceschi, is considered ante quem by Battisti (1971. p. 69) Salmi, who corrected many of Battisti's points in 1976, in 1979 dated the fresco to 1467.Hendy (1968, p. 149) places it during the 1470S. Waters (1901, p. 56) and Longhi recall rather the Greek aura in the Adamites lunette at San Francesco in Arezzo. The idea of the luminous reflection th at follows the edge of the figure is translated into a motif repeated by Giovanni di Francesco in the Bargello triptych, therefore before 1459. The luminous contrast between the marble door-frame, the figure and the background, the reduction of foreshortening to pure inlay, the metamorphosis of the white palmettes on the beams into grey are the origin of the tonal schemes that follow the Flagellation and forecast the Polyptych of the Augustinians.

According to Vermeule the figure derived from an ancient source that presented the mirror image of the Farnese Hercules; but the hand resting on the hip belongs to the repertory of the fifteenth century. Meiss noted the general resemblance to the Risen Christ on the fastening of the cope of St Augustine in Lisbon (Cat.no. 12:1). Salmi has demonstrated that this image has nothing to do with the supposed etymological derivation of Monterchi, Piero's mother's home town, from Mons Herculis (but see A. Paoluci, 1989, p. 64).

|

![]()