| |

|

Federico da Montefeltro was born in Castello di Petroia in Gubbio, the illegitimate son of Guidantonio da Montefeltro, lord of Urbino, Gubbio and Casteldurante, and Duke of Spoleto. Two years later he was legitimized by Pope Martin V, with the consensus of Guidantonio's wife, Caterina Colonna, who was Martin's niece.

On July 22, 1444, his half-brother Oddantonio da Montefeltro, recently created Duke of Urbino by Pope Eugene IV, was assassinated in a conspiracy: Federico, whose probable participation in the plot has never been established, subsequently seized the city of Urbino. However, the financial situation of the small dukedom being in disarray, he continued to wage war as condottiero. His first condotta was for Francesco I Sforza, with 300 knights: Federico was also one of the few condottieri of the time to have a reputation for inspiring loyalty among his followers.[1] In the pay of the Sforza—for Federico never fought for free—he transferred Pesaro to their control, and, for 13,000 florins, received Fossombrone as his share, infuriating Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta. Despite Federico's efforts, the Sforza sovereignty in the Marche was dismantled in the following years. When Sforza left for Lombardy, Sigismondo fomented a riot in Fossombrone, but Federico reconquered it three days later.

After six years in the service of the Florence, Federico was hired in 1450 by Sforza, now Duke of Milan. However, he could not perform his duties as he lost his right eye during a tournament. He subsequently carried a vast and disfiguring scar for the rest of his life, so that it was necessary to portray him only on his "good" side. Malatesta profited from his illness to obtain the position under Sforza, whereupon Federico in October 1451 accepted instead a proposal by Alfonso V of Aragon, King of Naples, to fight for him against Florence. After the loss of the eye, Federico – no stranger to conspiracies and one of the leaders that inspired Niccolò Machiavelli to write Il Principe – had surgeons remove the bridge of his nose (which had been injured in the incident). This improved his field of vision to a considerable extent, rendered him less vulnerable to assassination attempts – and, as can be seen by his successful career thereafter, restored his merits as a field commander.

In 1453 the Neapolitan army was struck by malaria, and Federico himself risked losing his healthy eye. The Peace of Lodi of the following year seemed to deprive him of occasions to exhibit his ability as military commander. In 1458 the death of both Alfonso and of his beloved illegitimate son, Buonconte, did not help to raise Federico's mood. His fortunes recovered when Pius II, a man of culture like him, became Pope and made him Gonfaloniere of the Holy Roman Church. After some notable exploits in the Kingdom of Naples, he fought in the Marche against Malatesta, soundly defeating him at the Cesano river near Senigallia (1462). The following year he captured Fano and Senigallia, taking Sigismondo Pandolfo prisoner. The Pope made him vicar of the conquered territories.

In 1464 the new Pope Paul II called him to push back the Anguillara, from whom he regained much of the northern Lazio for Papal control. The following year he captured Cesena and Bertinoro in Romagna. In 1466 Francesco Sforza died, and Federico assisted his young son Galeazzo Sforza in the government of Milan, and also commanded the campaign against Bartolomeo Colleoni. In 1467 he took part in the Battle of Molinella. In 1469, on the death of Sigismondo Pandolfo, Paul send him to occupy Rimini: however, fearing that an excessive Papal power in the area could also menace his home base of Urbino, once having entered Rimini Federico kept it for himself. After defeating the Papal forces in a great battle on August 30, 1469, he ceded it to Sigismondo's son, Roberto Malatesta.

The matter was solved by the election of Pope Sixtus IV, who married his favorite nephew Giovanni Della Rovere to Federico's daughter Giovanna, and gave him the title of Duke of Urbino in 1474; Malatesta married his other daughter Elisabetta. Now Federico fought against his former patrons the Florentines, caught in the Pope's attempt to carve out a state for his nephew Girolamo Riario. In 1478 Federico was involved in the Pazzi conspiracy.

However, after the death of his second wife Battista Sforza (daughter of Alessandro Sforza) he spent much of his time in the magnificent palace in Urbino. In 1482 he was called to command the army of Ercole I of Ferrara in his war against Venice, but was struck by fever and died in Ferrara in September.

Federico's son, Guidobaldo, was married to Elizabetta Gonzaga, the brilliant and educated daughter of Federico I Gonzaga, lord of Mantua. With Guidobaldo's death in 1508, the duchy of Urbino passed through Giovanna to the papal family of Della Rovere—nephews of Guidobaldo.

|

|

|

The Renaissance Man

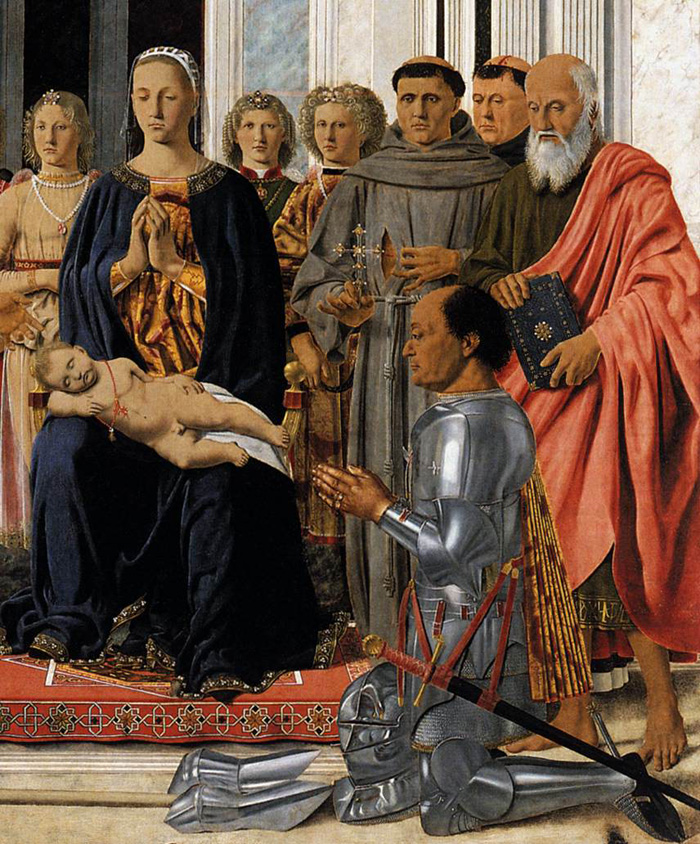

Federico, nicknamed "the Light of Italy", is a landmark figure in the history of the Italian Renaissance for his contributions to enlightened culture. He imposed justice and stability on his tiny state through the principles of his humanist education; he engaged the best copyists and editors in his private scriptorium to produce the most comprehensive library outside of the Vatican; he supported the development of fine artists, including the early training of the young painter Raphael. He ordered for himself the famous Studiolo di Gubbio File:Studiolo.jpg eventually purchased by and brought in its entirety to The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Edward IV of England made him a Knight of the Most Noble Order of the Garter; he wears the Garter bound round his left knee in the portrait by Pedro Berruguete.

Federico took care of soldiers who might be killed or wounded, providing, for example, dowries for their daughters. He often strolled the streets of Urbino unarmed and unattended, inquiring in shops and businesses as to the well-being of the citizens. All citizens, regardless of rank, were equal under the law. His academic interests were the classics, particularly history and philosophy.

All his personal and professional achievements were financed through mercenary warfare. Through dedication to the well-being of his soldiers, his men were enormously loyal and, incredibly, he never lost a war. He was decorated with almost every military honor including the English Order of the Garter.

|

|

|

The first historical references to Berruguette relate to his stay at Urbino. The great condottiere, Federigo di Montefeltro, duke of Urbino, had summoned Joos van Gent to decorate the library and study of his magnificent palace with allegories of the liberal arts and portraits of Biblical and pagan thinkers. Berruguete may have collaborated with him, but there is no doubt that the allegories and many of the more vigorous portraits of the series are by his hand alone (National Gallery, London, and the Louvre). He also painted the solemn portrait of Federigo and his son (Ducal Palace, Urbino), which gives some idea of his mastery of tactile values and of the airy qualities of physical space, perfectly suggested in depth. These paintings were all executed between 1480 and 1481. During his stay at Urbino, Berruguete completed a certain amount of work which has since remained in Italy. Moreover, he also painted the hands of the portrait of Montefeltro in the famous picture by Piero della Francesca in the Brera Gallery, Milan.

|

|

Federico da Montefeltro and his son Guidobaldo, by Pedro Berruguete. |

|

|

![]()