|

|

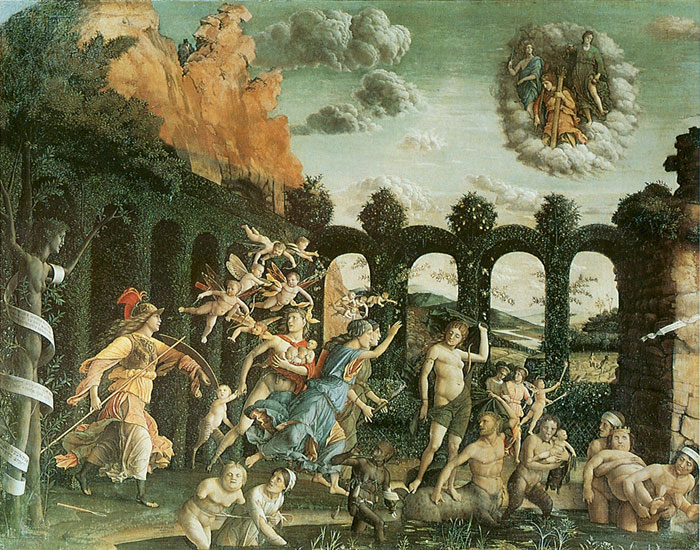

Andrea Mantegna, Triumph of the Virtue, about 1502, oil on panel, 160 x 192 cm, Paris, Musee du Louvre

|

|

Andrea Mantegna | Triumph of the Virtue |

| The Triumph of the Virtue (also known as 'Minerva Chases the Vices from the Garden of Virtue') is a painting by the Italian Renaissance painter Andrea Mantegna, executed in 1502. [1] It is housed in the Musée du Louvre of Paris. |

| In the spring of 1460, following the installation of the San Zeno Altarpiece in Verona, Andrea Mantegna finally decided to accept the invitation offered some four years earlier by the Marquis Ludovico Gonzaga of Mantua. From then until his death in 1506, Mantegna would serve as the official court painter of the Gonzagas, working successively under Ludovico (1444-1478), Federico (1478-1484), Francesco II (1484-1519) and the latter's demanding Ferrara-born wife Isabella d'Este (1474-1539). His first major commission was the decoration of the chapel of the Castello di San Giorgio, adjacent to the ducal palace, which Ludovico had adopted as his residence in 1458. Mantegna designed the ornamentation of the painted panels and the woodwork encrusted with precious stones, as well as the architecture. Unfortunately, drastic alterations made during the Cinquecento largely disfigured this masterpiece. It has been suggested that certain elements of this decoration project could be discerned in several esteemed paintings: the Adoration of the Magi, the Circumcision and the Ascension, today in the Uffizi Gallery, the Death of the Virgin in Madrid, and the Christ with the Virgin's Soul in Ferrara. These paintings are remarkable for their accuracy worthy of a miniaturist. However, despite the monumental spectacle on view in these works, particularly in the Circumcision, it is also important to recognize the lyrical realism that emanates from certain details such as the scalpel, the pouting child or, in the Death of the Virgin, the landscape in the background with the view of the lake of Mantua. Mantegna's masterpiece of the Mantua period, nine years in the making, occupying the artist from 1465 to 1474, is the series of frescoes covering the walls of what is known today as the Camera degli Sposi (The Spouses' Room) representing the various members of the Gonzaga family busy with their daily tasks. With this work, Mantegna reached the pinnacle of his illusionist creativity: the painted oculus on the ceiling, bringing to mind a great circular opening to the sky, with clouds floating by, lends a three-dimensional quality to the figures depicted. Typically dated from about 1470-1475, the Saint Sebastian in Vienna has Mantegna giving free rein to his passion for epigraphy, inscribing his signature in the stone in Greek letters. We also note in this work an anthropomorphic cloud--an innovation that also surfaces in the ceiling of the Camera degli Sposi and the Minerva in the Louvre. These symbolic details, combined with the morbid dignity suffusing the face of the saint in agony, made this painting and its creator a beacon for the international culture of decadence of the late 19th century. Art in Tuscany | Andrea Mantegna, Camera degli Sposi The Studiolo of Isabella d'Este (1491-1502) The first work commissioned by the newly minted marchioness Isabella d'Este for her studiolo at the Castello di San Giorgio -- references to which may be found as early as November 1491 -- appears to have been Mantegna's painting Mars and Venus known as Parnassus, which was completed in 1497. Painted on canvas, as was the case for the other works commissioned for the studiolo, it celebrates the illicit love affair of Mars and Venus whose union resulted in the birth of Cupid. In the eyes of several contemporaries, the allusion to Francesco II and Isabella was obvious: the exceptional virtues of the princely couple were portrayed to explain the remarkable blossoming of the arts at the court of Mantua. It is not known whether or not a full decorative and symbolic plan for the entire studiolo existed at its creation. In any event, for five years, Mantegna's Parnassus was the only painting displayed. Isabella's letters lead us to conclude that the marchioness had wanted to commission paintings that would be "fraught with meaning" from the most celebrated painters of the time: she tried in vain to obtain the collaboration of Giovanni Bellini, Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) and Francesco Francia (around 1450-1517). By 1502, Mantegna had completed the second painting in the series, Minerva Banishing the Vices from the Garden of Virtue. His philosophical intent, embodied in very personal inventions, remains extremely complex, despite a multitude of inscriptions designed to elucidate his purpose. At the request of Isabella almost twenty years later, on the occasion of her decision to move her studiolo to the Corte Vecchia, Correggio would provide a response to Mantegna in his Allegories of Vices and Virtues. The exhibition brings together all of the paintings displayed in the second studiolo, as all seven works are in the Louvre's collections. For more than thirty years, the decoration of her studiolo was a prime concern for Isabella, and she was always careful to adapt its presentation to the new sensitivity of the court, an ideal of literary and sentimental humanism. In order to cleave to these more lyrical tastes, Mantegna was compelled to leave behind his archaeological and austere approach, bending his imagination to the moralizing allegories then in fashion. Despite his efforts, Isabella seemed to prefer the tender and sentimental work of Perugino and the Ferrara native Lorenzo Costa, who arrived in Mantua in 1506 to succeed Mantegna as court painter. [2]

|

||

|

||

| Sources Mauro Lucco, ed (2006). Mantegna a Mantova 1460-1506. Milan: Skira. Press release | Mantegna exhibition at Musée du Louvre, Hall Napoléon | From September 26, 2008 to January 5, 2009 | www.mini-site.louvre.fr/mantegna [1] Andreas Mantegna is one of the greatest of the Italian Renaissance Artists. A virtuoso, who was deeply inspired by Classical Art and Literature, he was highly skilled in Foreshortening, Perspective, and creating magnificent visual illusions that draw the viewer in to participate in the painted scene. Born in 1431 in the North Italian village of Isola di Carturo, Andreas Mantegna was the son of a carpenter called Bagio. It was usual then for sons to follow their father's trade, but Mantegna's talent must have become apparent at a very young age and he was earmarked for an artistic career. When he was ten, he came to the notice of Francisco Squarcione, an artist from Padua, and was formally adopted by him. Francesco Squarcione had several other adopted sons. His motive was not a fondness of children, but a cold, business-minded outlook. He took in talented youngsters, put them to work on art projects undertaken by his Studio, and kept their earnings. Life with Squarcione was not easy. Mantegna was too bright not to realize he was being exploited and was already too much of a forceful personality to take it lying down for long. They had plenty of bitter squabbles and finally, when Mantegna was seventeen, ended up in court to have the legal adoption rescinded. This enabled Mantegna to keep all the money he earned and move on to better prospects. Still, the years spent in Squarcione's studio provided Mantegna with valuable training and also exposure to the culturally rich atmosphere of Padua. This famous University town attracted intellectuals, artists, and writers from around Italy and beyond, all converging to work, learn and exchange ideas. Living in this exciting hub had a profound effect on young Mantegna. At the time, there was considerable revived interest in the antiquities of Ancient Rome and Greece, and many of these statues and paintings found their way to Padua where Mantegna saw them and fell immediately under their spell. His interest in classical antiquities was to be a life-long one. He preferred studying classical statues to observing from nature, a habit that Squarcione greatly derided. According to him, this made Mantegna's figures appear hard and lifeless, like they were made of marble. It seems this criticism really stung Mantegna, and much later, when he painted the famous painting 'St. Sebastian', he painted a marble sculpted foot beside the Saint's flesh and blood foot, and we can see for ourselves the non-validity of Squarcione's assertions. Aside from his passion for the art of the ancient world, Mantegna was greatly influenced by the works of Jacopo Bellini and his sons Gentile and Giovanni Bellini, Rogier van der Weyden, Piero della Francesca, Paolo Uccello, and Donatello. Mantegna really came out on his own as an artist after splitting with Squarcione. Shortly afterwards, he was given the very important commission of working on frescoes for the Ovetari Family Chapel in the Eremitani Church. The project initially included three other older artists, but they dropped out one after the other, and, in the end, it was Mantegna alone that completed the work. The Eremitani Fresco Series, completed in 1457 and showing an extraordinary grasp of perspective and composition, included the works 'Baptism of Hermogenes', 'St. James before Herod Agrippa', 'St. James Led to Execution', and 'Matyrdom of St. James'. These masterpieces were destroyed during the Second World War, when American bombs, as usual, got the wrong target – the Eremitani Church instead of the Padua Railway Yards. Mantegna next worked on the 'Cruxifixion' altarpiece for the Church of San Zeno. Around this time, Mantegna got married to Jacopo Bellini's daughter Niccolosia and was offered the prestigious position of Court Artist to Lodovico Gonzaga II, the Marquis of Mantua. After much deliberation and hesitation, Mantegna accepted and, except for a brief stay in Rome to work for Pope Innocent VIII, remained in the service of the Mantuan Court for the rest of his life. Mantegna really flourished in Mantua. Although he could be a rather temperamental and problematic individual, Lodovico and his successors, Frederico and Gianfrancesco, always held him in the very highest esteem, and, well paid, he was able at last to indulge in his passion for collecting classical antiquities. He built up quite a collection, and, well inspired, painted some of his best works here, trying out his hand at everything from religious altarpieces and frescoes to purely allegorical paintings. Some notable mentions are his panels for the Gonzaga Castle Chapel - 'Adoration of the Magi', 'Ascension', and 'Circumcision'. Two study trips to Florence inspired him to paint the famously foreshortened 'Dead Christ', a remarkable work that leads one to be somewhat prepared for the grand ceiling illusion of the 'Camera degli Sposi'. This fresco, finished in 1474, gives the impression of a very high ceiling with circular sky opening, from which Court Ladies, Putti and even a peacock look back down at us; there is a heavy tub of plants balanced rather precariously overhead on a rod, all set to tumble down on Mantegna's critics, no doubt. Other remarkable paintings of this period include 'Lodovico Gonzaga, his Family and Court' and 'Servants with Horse and Dog', both works giving us an insight into the life at the Mantuan Court. After this success, came the 'Triumph of Caesar' series, a body of work that Mantegna himself considered the high point of his career. It was while he was painting these series that he was summoned, in 1488, by the Pope to Rome. He remained two years to paint a chapel that was, unfortunately, destroyed in 1780. On his return to Mantua, where the Court was now dominated by Gianfrancesco Gonzaga's new and intellectually brilliant wife Isabelle d'Este, he was asked to paint the mythological paintings ''Parnassus' and 'The Triumph of Virtue' for her study. He also painted many sculpture-like monochrome works like 'Samson and Delilah' and 'Introduction of the Cult of Cybele into Rome'. In his last years, Mantegna was troubled by financial concerns and was forced to sell some of his Classical collection to Isabelle d'Este; most heart-breakingly of all, his beloved Roman bust of the Empress Faustina. A few weeks later, on 13 September 1506, Mantegna died at the age of 75. [References: |

||||

Art in Tuscany | Art in Tuscany | Giorgio Vasari | Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects |

||||

|

This page uses material from the Wikipedia articles Andrea Mantegna and Triumph of the Virtues (Mantegna), published under the GNU Free Documentation License. |

||||

Holiday homes in the Tuscan Maremma | Podere Santa Pia |

||||

Podere Santa Pia |

Podere Santa Pia, garden |

View from terrace with a stunning view over the Maremma and Montcristo |

||

Crete Senesi, surroundings of Podere Santa Pia |

Montefalco |

Florence, Duomo |

||

|

||||

The abbey of Sant'Antimo |

Cortona |

Spoleto, Duomo |

||

| Isabella d’Este’s Studiolo |

||||

The fashion of studioli, or private studies, small rooms reserved for intellectual activities, spread in the 15th century in the Italian courts, bathed in Humanist culture.

Isabella d’Este, who married Francesco II in 1490, rapidly decided to create a studiolo in a tower of the old Castello di San Giorgio. The work on this project lasted more than twenty years. |

|

|||